Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (11 page)

1

. Kimball (ed.),

Churchill & Roosevelt, The Complete Correspondence

, Volume I, p. 286

2

. Smith, Jean Edward,

FDR

, p. 542

3

. Meiklejohn, Diaries, Reel 52. Harriman had also brought over the gift of an electric shaver which the Prime Minister wanted to use constantly. Voltages were of course a problem.

4

. Churchill, Volume III, p. 538

5

. Harvey (ed.), p. 70

6

. Kimball (ed.), p. 286

7

. Ive, p. 72

8

. Richardson, pp. 84-85. Jacob joined Churchill on the

Duke of York

.

9

. Soames (ed.),

Speaking For Themselves

, p. 461

10

. Pawle,

The War and Colonel Warden

, p.145

11

. Martin, John,

Downing Street; The War Years

, p. 69

12

. Gilbert,

Churchill

, Road to Victory, 1941-1945, Volume VII, p. 18

13

. Pawle, London 1963, p. 146

14

. Gilbert,

Churchill

, Volume VII, p. 18

15

. Gilbert,

Churchill

, Volume VII, p. 9

16

. Richardson,

Diary

, p. 88

17

. Leasor (ed.),

War at the Top, The Experiences of Sir Leslie Hollis

, p. 29

18

. Goodwin,

No Ordinary Time

, p. 301

19

.

Time

magazine, 5 January, 1942

20

. Roberts,

Masters and Commanders

, p. 84

21

. Fields,

My 21 Years in the White House

, p. 81

22

. Goodwin, p. 302

23

. Stiegler, Sam, interviews. From Medford Afro-American Remembrance Project, p. 7

24

. Fields, p. 51

25

. François Rysavy as told to Frances Spatz Leighton,

A Treasury of White House Cooking

, p. 79

26

. Lady Williams, In conversation with the author, April 2010

27

. Macmillan,

Tides of Fortune

, p. 322

28

. Graebner,

My Dear Mr. Churchill

, p. 53

29

. Harriman papers, Box 446, Folder 2

30

. Nesbitt, Henrietta,

White House Diary

, p. 30

31

. Nesbitt, p. 273

32

. Jenkins,

Churchill: A Biography

, p. 672

33

. Bohlen,

Witness to History,

1929-1969, p. 143

34

. Burns,

Roosevelt, The Soldier of Freedom, 1940-1945

, p. 178

35

. Nesbitt papers, Library of Congress

36

. Whitcomb, John and Claire,

Real Life at the White House

, p. 306

37

. McGowan, Norman,

My Years With Churchill

, 1958, p. 70

38

. Roberts p. 68

39

. Roberts, p. 69

40

. Jenkins, p. 672

41

.

New York Times

, 11 January 1942

42

. Bercuson and Herwig,

One Christmas in Washington

, p. 154

43

. Goodwin, p. 302

44

. Gilbert, Volume VII, p. 27

45

.

Ibid

.

46

. Gilbert, Volume VII, p. 28

47

. Richardson, p. 91

48

. Bercuson and Herwig, p. 164

49

. Moran, p. 12

50

. Roberts, Masters, p. 84

51

. Pawle, p 155

52

. Roberts p. 77

C

hurchill believed that his persuasive powers and personal charm would be effective not only with a well disposed ally like Roosevelt, but even with a far less congenial one like Joseph Stalin. Which is why he launched his usual first-phase tactic, one that had worked so well with Roosevelt: a

personal

letter-writing campaign. This began in June 1940, when he used the occasion of the appointment of Sir Stafford Cripps as British Ambassador to the Soviet Union to contact the Soviet leader directly.

Churchill had reason to regard this exercise of personal diplomacy a success: by July 1941 he and the Soviet leader

were exchanging birthday greetings,

3

and Stalin

immediately

responded affirmatively to Churchill’s request for a meeting.

Getting to Moscow required stopovers at Gibraltar, Cairo and Teheran for refuelling. As usual, Churchill turned these stops on an arduous journey to his advantage, finding time at Teheran for both his beloved baths and lunch with the Shah. In Teheran, amid an “atmosphere of deck chairs and whiskey and soda”, Churchill escaped the “continuous

hooting

of the Persian motor cars”

4

and the heat by spending the night at the British summer legation high in the mountains above the capital. Not every Churchill whim was catered to. The Prime Minister’s request that his bed at the legation in Teheran be dismantled, carted up to the cooler mountains and there reassembled, was refused. One of Churchill’s

wartime

private secretaries, Leslie Rowan, and Commander Thompson spent the night in “a magnificent Persian tent in the garden” of the summer legation.

5

Dinner at the legation featured turkey with all the trimmings.

6

A British bodyguard recalls the dessert served up by the kitchen staff. A large plate of fresh Persian peaches with the tops cut off were filled with melted chocolate and topped with whipped cream. Then the top was replaced “at a jaunty angle”.

7

On his arrival in Moscow on the evening of 12 August 1942, after the usual airport ceremony, Churchill promptly went to his villa eight miles outside Moscow. He was, as he put it “regaled in the dining room with every form of choice food and liquor, including caviar and vodka, but with many other dishes and wines from France and Germany, far

beyond

our mood or consuming powers”.

8

The 67-year-old Churchill, despite the long flight, insisted

on an immediate appointment with Stalin – though he did take some time to bathe. He also took time to feed the

goldfish

at the villa Stalin had assigned him. Alexander Cadogan, the Foreign Office’s permanent Under-Secretary, ever

interested

in food, noted there were excellent raspberries growing in the gardens of the villa.

Churchill had two reasons for anticipating a tough slog in Moscow. First was his long-standing and well-known

hostility

to Communism, Bolshevism, and all that the Stalin

regime

represented. He had made no secret of his desire to see the regime toppled in 1919, and had cooperated with efforts to overthrow it. But in 1942, as he put it, “If Hitler invaded hell, I would make at least a favourable reference to the devil in the House of Commons”.

9

Stalin was to be wooed, but at dinner the Prime Minister would presumably dine with a rather long spoon.

His second reason for anticipating a difficult meeting was the news he was bringing to Stalin: there would be no second front in Europe in 1942 to ease the pressure on Soviet forces fighting on the Eastern front. Before the meeting, Churchill had written obliquely to the Soviet leader: “We could …

survey

the war together and take decisions hand-in-hand. I could then tell you plans we have made with President Roosevelt for offensive action in 1942.”

10

That action was Operation Torch in North Africa, rather than the cross-Channel

invasion

that Stalin favoured.

So worried was Churchill about this visit that he had

decided

to take Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s emissary, with him. He had written to the President: “Would you be able to let Averell come with me? I feel that things would be easier if we all seemed to be together. I have a somewhat raw job.”

11

Roosevelt promptly agreed.

The food laid out on his arrival at his dacha was not the only display of Stalin’s hospitality. One aide recalls the breakfasts the Soviets provided: “caviar, cake, chocolates, preserved fruit, grapes, none of the normal breakfast dishes. Fortunately coffee and an omelette appeared and all was well. Leslie Rowan told me that when he asked for an egg and bacon, they produced four eggs and nine rashers of

bacon

– all very nice except that one remembers that the vast majority of the population are practically starving”.

12

This may be why Churchill later described his quarters as being “prepared with totalitarian lavishness”.

13

Churchill set off for his first meeting with the man he called “the great Revolutionary Chief and profound Soviet Union statesman and warrior”.

14

The meeting, not a dinner, lasted from seven to eleven p.m.

Although it began badly, as Churchill had anticipated, in the end, after Stalin reacted positively to tales of the British bombing of Germany, it ended on a sufficiently cordial note for Churchill to tell Sir Charles Wilson: “When I left we were good friends and shook hands cordially. I mean to forge a solid link with this man.”

15

That left Churchill to dine alone. “It was now after

midnight

, and the PM, who had had no dinner, proceeded to eat a huge meal. Presently, he put his half-finished cigar across the wine glass. He was plainly very weary.”

16

It is unclear whether an entirely new feast had been prepared, replacing what had been set out earlier, as original records may have been destroyed by the Ninth Directorate of the KGB, which was then in charge of serving the elite.

17

Discussions the following day proved fruitless. Churchill could pry no response from Stalin other than a repeated

demand

for a second front, prompting a disgruntled Churchill

to announce to his staff that further meetings would be

useless

. He did, however, feel compelled to stay for Stalin’s

closing

official banquet for his own staff and the British guests – some hundred in all – the following night.

The menu did not reflect any wartime food shortages in the hard-pressed Soviet Union.

HORS D’OEOEUVRES (Cold)

Caviar (soft). Caviar (pressed). Salmon. Sturgeon.

Garnished herrings. Dried herrings. Cold ham. Game

Mayonnaise. Duck. Soused sturgeon. Tomato salad. Salad

Payar. Cucumber. Tomatoes, radishes. Cheese.

HORS D’OEOEUVRES (Cold)

White mushrooms in sour cream. Forcemeat of game.

Egg-plant meunier.

DINNER

Creme de poularde

Consommé borsch

Sturgeon in champagne

Turkey chicken partridge

Potato purée

Suckling lamb with potatoes

Cucumber salad cauliflower

Asparagus

Ice-Cream fruit ices

Coffee liqueurs

Fruit petit fours roast almonds

18

“The dinner dragged on,” moaned Churchill’s doctor, “the list of toasts – 25 of them – appeared interminable.”

19

Churchill later told Sir Charles: “The food was filthy.” As was the Prime Minister’s changeable mood. Being assigned the place of honour on the Soviet leader’s right was no

compensation

for the abuse to which Churchill felt he and his

entourage

were still being subjected. Unusually, Churchill wore his siren suit to this dinner instead of the traditional black tie that he often wore for such formal banquets.

At seven o’clock the next evening, after a day of staff meetings, Churchill went to see Stalin to say goodbye as he planned to leave Moscow early the following morning. The possibility that his ally would leave contemplating an open breach had its intended effect on Stalin, who quite

unexpectedly

invited Churchill to his Kremlin apartment for drinks. “I said that I was in principle always in favour of such a policy,”

20

responded Churchill.

Drinks became dinner, and what a dinner it was. This dinner was as close to the one-on-one, table-top

diplomacy

that Churchill preferred as anyone was ever likely to get in the Kremlin. It included interpreters, both A.H. Birse (stepping in at the last minute for Churchill) and Vladimir Pavlov (for Stalin), and, at Stalin’s suggestion, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Even the serving staff was minimal: this apparently impromptu dinner was on a serve-yourself basis. Stalin brought in his daughter, Svetlana, to meet Churchill, and uncorked various bottles, “which began to make an

imposing

array.”

21

At first, Stalin ate very little. The Prime Minister reported that even after some three to four hours of talk – just the sort of substantive conversation that Churchill had always assumed would more likely produce results in the informal

setting of a private dinner than in a meeting room – “there was no response from this hard-boiled egg of a man.”

22

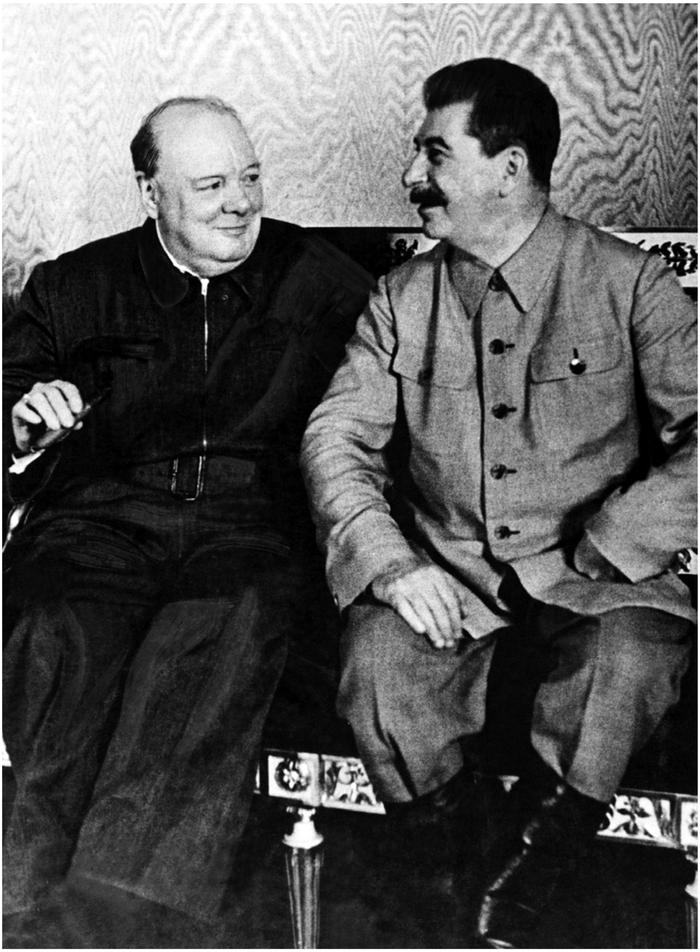

New allies. With Stalin, Moscow, 14 August 1942

Churchill later recalled:

Dinner began simply with a few radishes, and grew into a banquet – a suckling pig, two chickens, beef, mutton,

every

kind of fish. There was enough to feed thirty people. Stalin spoilt a few dishes, a potato there, an oddment there. After four hours of sitting at the table, he suddenly began to make a hearty meal. He offered me the head of a pig, and when I refused, he himself tackled it with relish. With a knife he cleaned out the head, putting it into his mouth with his knife. He then cut pieces of flesh from the cheeks of the pig and ate them with his fingers … Of course we waited on ourselves.

23

Perhaps any disgust on Churchill’s part was tempered by his life-long fascination with the exotic, and undoubtedly by his sense of triumph at breaking through the frost that had characterised Soviet–UK relations. He cabled Clement Attlee, the Deputy Prime Minister, in London: “I have just had a long talk, with dinner lasting six hours, with Stalin and Molotov alone in his private apartment … We …

parted

on most cordial and friendly terms …”

24

The Prime Minister returned to his villa at a quarter past three on the morning of 16 August, convinced his special brand of personal diplomacy, practised at a private dinner, had succeeded. We “ended friends,”

25

Churchill told Wilson as he left for a four-thirty flight to Teheran, and reported to the Cabinet, with a copy to President Roosevelt, that he had had “an agreeable conversation” with the Soviet leader. “I am definitely encouraged by my visit to Moscow.”

26

Once in Teheran, Churchill again rested in the British summer legation. Then on to Cairo, and, after

recuperating

from understandable fatigue, inspecting the troops,

several

meetings and a visit to Montgomery’s forward position, back to London.