Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (7 page)

The Prime Minister also spent some time deciding what to serve the President for lunch on such a momentous day. He wanted food that was “unusual, seasonable and

definitely

British … decided to take grouse … It was arranged that sufficient birds for the luncheon party, and an extra brace for the President, should be put on the train at Perth”.

16

Duff Cooper had “bagged the grouse in Scotland; on the PM’s orders, another dozen brace had been frozen and brought along as a gift for the president”.

17

H.V. Morton, a British journalist and best-selling travel writer, invited along on the trip by Brendan Bracken, then Minister of Information,

18

noted:

It is typical of the Prime Minister that he should have remembered it was once the custom of the Lords of the Admiralty when they voyaged abroad to take with them a turtle, which they were entitled to draw from a naval establishment. This strange custom began when Britain, in order to watch Napoleon at St. Helena, took over Ascension Island and every warship on its way to England from Ascension Island brought a turtle home with it … Mr. Churchill might have been hard put to it to discover a turtle in war-time London. Nevertheless he served turtle soup to the President. It so happened that Commander Thompson, who had heard Mr. Churchill wish for a turtle, was in a grocer’s shop in Piccadilly and, noticing some bottles of turtle soup and

finding

that neither coupons nor ration books were required for them, promptly bought them and took them back in triumph to No. 10.

19

Churchill had great affection for animals. When First Lord of the Admiralty, in 1911, on first exploring HMS

Enchantress

, the Admiralty yacht, he found a “tank of turtles, to be turned into soup. He was much moved by their plight and ordered their immediate release”.

20

That affection did not always prevail over Churchill’s appetite.

During his visit to Williamsburg, Virginia, in March 1946, he apparently specifically requested Maryland diamondback terrapin. His hosts agreed that “the world’s first citizen should have the world’s first food if available” and so we must assume that Churchill’s request was granted.

21

One last word on turtle soup. To celebrate 50 years in the House of Commons, on 31 October 1950, the Conservative Party gave a dinner at the Savoy in Churchill’s honour, with turtle soup a feature

“Each course traced his Parliamentary life from election in Oldham in 1900. Turtle soup au sherry d’Oldham, and other courses named after some of his constituencies. Fillets of Sole after the Cinque Port, Mushrooms Epping Forest, from his 1924-1945 electorate, followed. Partridge on toast with English sauce Clementine. Les petits pois d’un grand ami de la France.”

22

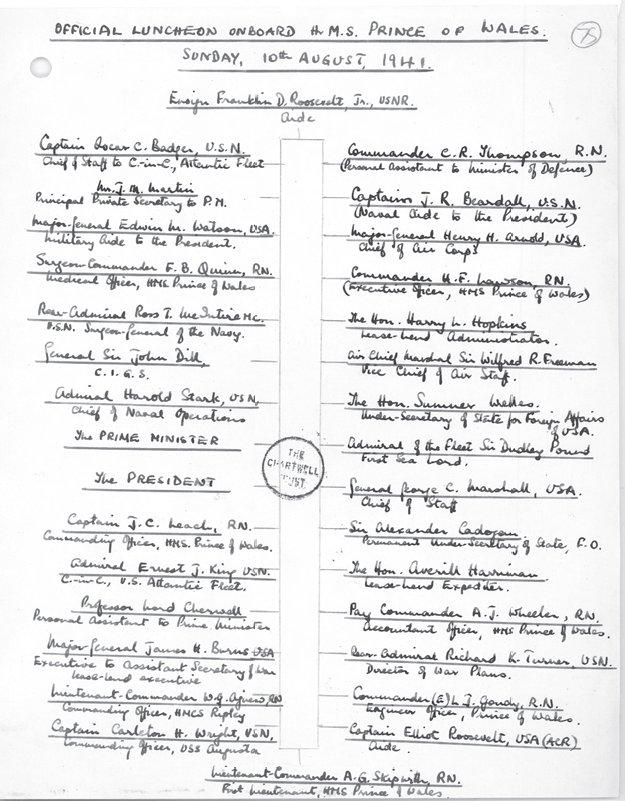

Thirty-two men sat down for lunch that Sunday to eat Hopkins’ ever-present caviar, along with smoked salmon and roast grouse and the symbolic turtle soup. The menu

was printed below the Prime Minister’s cypher. No wines are listed.

Churchill reciprocates, 10 August 1941

Certainly there were differences between the conditions faced at home by American and British officers and sailors. One country had been at war for two years, the other at peace. Morton commented on the advertisements in the magazines he found on board the American ships featuring “almost

eatable

coloured photos of gigantic boiled hams, roast beef and other rationed food, to say nothing of rich, creamy puddings …”

23

Another difference: by tradition, all US Navy ships are dry. British ships are not. This made British ships the popular place for meetings, especially around cocktail hour. The presidential party, fortunately, was not subject to the usual US Navy rules and Roosevelt’s reputation among the British for mixing a martini with deadly Argentine vermouth

24

probably got its start at dinner on 9 August aboard the USS

Augusta

. The Americans quipped:

The American Navy visits the British Navy in order to get drink, and the British Navy visits the American Navy in order to get something to eat.

25

Roosevelt, sensitive to British privations, made a gesture of great courtesy and directed that every British seaman on the

Prince of Wales

and the other ships be given a gift box of American foods. Morton describes “a pyramid of something like one thousand five hundred cardboard

cartons

, which a chain of American sailors had soon stacked on our quarter-deck. Each box contained an orange, two apples, two hundred cigarettes, and half a pound of cheese, with a card saying it came from the President of the United States.”

Churchill and the presidential gift boxes for every British seaman

On 10 August, Churchill boarded the USS

Augusta

, this time to dine in a smaller group with the President. The diary of Churchill’s Principal Private Secretary, John Martin, records “a straightforward American meal of

tomato

soup, roast turkey with cranberry sauce and apple pie with cheese”.

26

The dishes’ lack of sophistication might have reassured the Prime Minister and his team that although they could not match the Americans in quantity, when it came to culinary skills, Britain retained its superiority.

While the leaders were meeting, both staffs

continued

their separate rounds of dinner-table diplomacy. On 10 August, Cadogan gave a dinner on the

Prince of Wales

for American generals, admirals and Sumner Welles, then Under-Secretary of State and one of the President’s chief advisers. At Churchill’s direction, and with Roosevelt’s keen

endorsement, these staff meetings, at all levels, would

continue

to the end of the war. They were the initial steps in a plan, brought to fruition during Churchill’s stay in the White House in December 1941, to create a new Combined Chiefs of Staff Committee to prosecute the war.

These day-long sessions, the sharing of opinions and

experiences

, the informality created by the many lunches and dinner meetings, established an invaluable camaraderie between the British and the American military and political staffs, and their leaders. One sign of this developing

friendship

was a letter and package given by Harry Hopkins to John Martin, Churchill’s Principal Private Secretary. The box contained a large supply of foods hard to find in

wartime

Britain. The accompanying letter, on White House stationery, reads:

My dear Martin, if your conscience will permit, these are to be taken to London. If the niceties of the war would disturb, I suggest you give them to some other member of the party whose will to live well may be greater than yours.

Ever so cordially, Harry Hopkins

27

The meetings resulted directly in the joint statement of Allied goals known as the Atlantic Charter. They also had two further important consequences: the military staffs took the first steps towards future cooperation in the

execution

of the war, and they established a pattern for what would become known as summit meetings – in Churchill’s own words, almost a decade later, a “parley at the summit”.

28

No one says it better than Sir Martin Gilbert:

On these secret commitments and declarations the British

policy-makers and planners were to build their detailed

preparations

in the months to come, despite formidable obstacles of priority and production. For Churchill, it was the fact that he had established a personal relationship with the President, which constituted the main achievement of ‘Riviera’”

29

as this first summit was then code-named.

Three weeks later, back in London, the Prime Minister attended a lunch given by Ambassador Ivan Maisky at the Soviet embassy to mark their new-found comradeship. The two main planks of Churchill’s Grand Alliance, the Soviet Union and the United States, were now in place.

Celebrating the Alliance

Churchill and Soviet Ambassador Maisky’s tête-à-tête: lunch at the Soviet embassy, London, August 1941

1

. FDR to WSC on the occasion of FDR’s 60th birthday, in response to the Prime Minister’s birthday wishes, Moran, p. 25

2

. Larson, Philip P., “Encounters with Chicago”,

Finest Hour

118, p. 30.

3

. McJimsey,

The Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

, p. 138

4

. Churchill,

The Second World War, The Grand Alliance

, Volume III, p. 427

5

. Colville, p. 415

6

. Colville, p. 368

7

. Colville, p. 369

8

. Dilks, David (ed.),

Cadogan

, p. 395

9

. Morton, H.,

Atlantic Meeting

, p. 74

10

. Dilks (ed.), p. 396

11

. Joan Bright in conversation with the author

12

. Lash,

Roosevelt and Churchill, 1939-1941

, p. 391

13

. Gilbert (ed.),

The Churchill War Papers

, Volume 3, p. 1036

14

. Lash,

Roosevelt and Churchill

, p. 391

15

. Wilson, Theodore,

The First Summit

, p. 92

16

. Morton, p. 104

17

. Wilson, p. 104

18

. Although the press was barred, Morton and Howard Spring, a novelist, were invited to go along to describe what they saw. They were not told where they were going and were sworn to secrecy by Brendan Bracken. Morton asked an important question: “Should I pack a dinner jacket?” Bracken said, “yes”.

19

. Morton, p. 105

20

. Montague Browne,

The Long Sunset

, p. 230

21

. Langworth, Richard, “On Turtles and Turtle Soup”,

Finest Hour

146, p. 25

22

. CHUR 2/96B/224

23

. Morton, p. 95

24

. Wilson, p. 106

25

. Richardson,

From Churchill’s Secret Circle to the BBC: The Biography of Lt. Gen. Sir Ian Jacob

, p. 67

26

. Martin,

Downing Street: The War Years

, p. 59

27

.

Ibid

., photo insert following p. 56

28

. Gilbert,

Churchill: A Life

, p. 889

29

. Gilbert, Volume VI, p. 1168