Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (19 page)

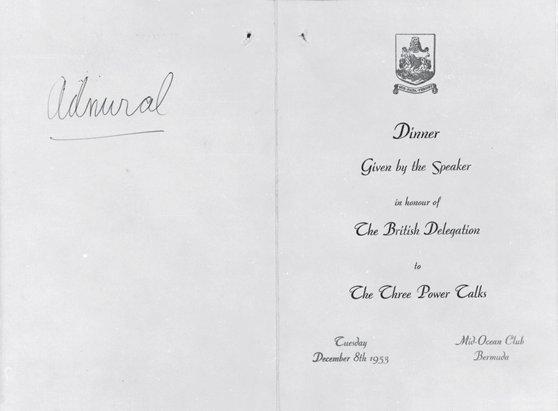

On 8 December the summit concluded and the conference room at the Mid Ocean Club was hastily converted into a formal dining room.

9

The Speaker of the Bermuda

Assembly

gave a dinner to celebrate “The Three Power Talks”. But since both the President and the French representatives had left that morning before the official banquet, so only the British delegation was present. As was the custom, the

Speaker

proposed the first toast to the Queen. After other toasts, Churchill replied “as principal speaker, and did it very well”, in John Colville’s opinion.

10

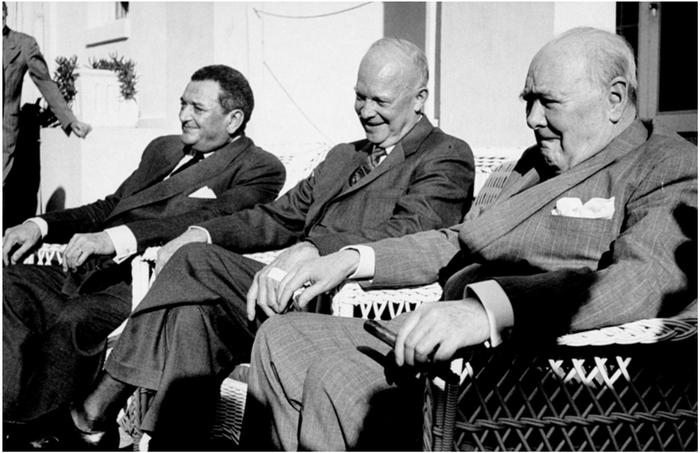

The Big Two and the French Premier, Laniel

Fifty years later, on 8 November, 2003, the Churchill Centre gave an anniversary lunch at the Mid Ocean Club. The menu for the buffet lunch was contemporary, more varied than the December 1953 original, with lighter foods

more appropriate to Bermuda’s summery weather. The drinks offered were certainly different: hard liquor (only on a “cash basis”) and “bottles of wine on tables, mostly white, $30.00”. Rather different from the elegant wines served at the 1953 dinner. Flowers were “to be inexpensive”.

11

Guests arrived by bus. It is difficult to imagine the Prime Minister and the President, after a hard day of bargaining, queuing

up for a self-service meal, although Churchill was no

stranger

to the trying venues of wartime Europe and willingly

consumed

sandwiches while on the campaign trail.

Menu for the Bermudians’ dinner honouring the British Delegation

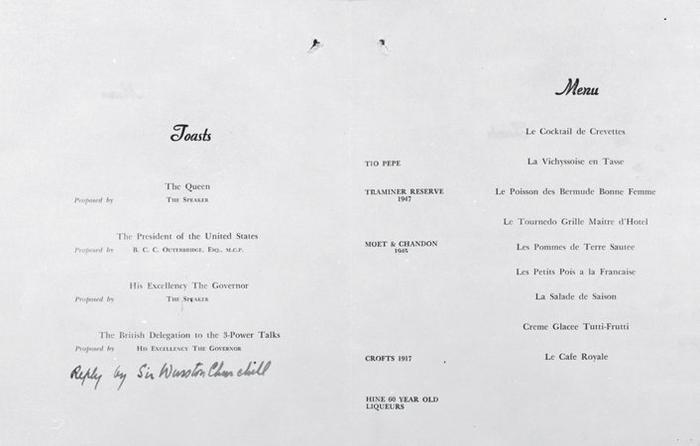

It should come as no surprise that Churchill left Bermuda still determined to arrange one more Big Three summit, a dream unrealised.

Churchill alone, Bermuda

1

. Westminster College Archives Press Release, 14 February 2006

2

. PREM 11/418. Full text of telegram in Churchill and Bermuda 20th International Conference November 2003.

3

. Churchill, “Land of Corn and Lobsters”,

Colliers

magazine, August 1933, p.133

4

. Westminster College, Fulton. Missouri, Press Release 14 February 2006

5

. Richards, Michael, “Commissioning Day”,

Finest Hour

110, p.15

6

. PREM 11/418

7

. Gilbert, Volume VIII, p. 807

8

.

Ibid

., p.936

9

. Colville,

Fringes

, p. 688

10

.

Ibid

.

11

. Mid-Ocean Club, 8 November 2003

“When I dine after a hard day’s work, I like serenity, calm, good food, cold beverages.”

1

“Give me a few well-cooked dishes I can really enjoy.”

2

“

I

t is well to remember that the stomach governs the world,” wrote Churchill when planning the feeding of his troops on the north-west Indian frontier at the tail-end of the

nineteenth

century.

3

His stomach was often on his mind, perhaps because of his intermittent struggle with indigestion, which he called “indy”, and about which he consulted the eminent gastroenterologist, Dr. Thomas Hunt.

Dr Thomas Hunt, of 49 Wimpole Street, in addition to certain dietary suggestions, offered Churchill the wise

advice to exercise “not more than twice a day – and no longer than 15 minutes.”

4

Many years later, in 1954, after a discussion about which scales were in fact accurate in showing his true weight, a tomato diet had been suggested to Churchill. He wrote to his wife that he “had no grievance against the tomato but I think I should eat other things as well.”

5

Churchill at dinner, cartoon by Vicky

Over the years, his aides came to understand the

imperative

of “tummy-time”. Flying to Washington in June 1942, Churchill referred to his “tummy-time” as determining when meals should be served in flight, saying that he “didn’t go by sun time … but by ‘tummy-time’ and I want my dinner.”

6

(When he landed, he went on to the British embassy for a second dinner.) In 1943, he left Washington, flying to

Newfoundland, thence to Gibraltar and on to Algiers. He slept in his flying boat but insisted that his meals be served at his “‘stomach-time’ without regard to changing time zones.”

7

In 1944, Churchill sardonically suggested that there be a “series of Cabinet banquets, a sort of Salute The Stomach Week”.

8

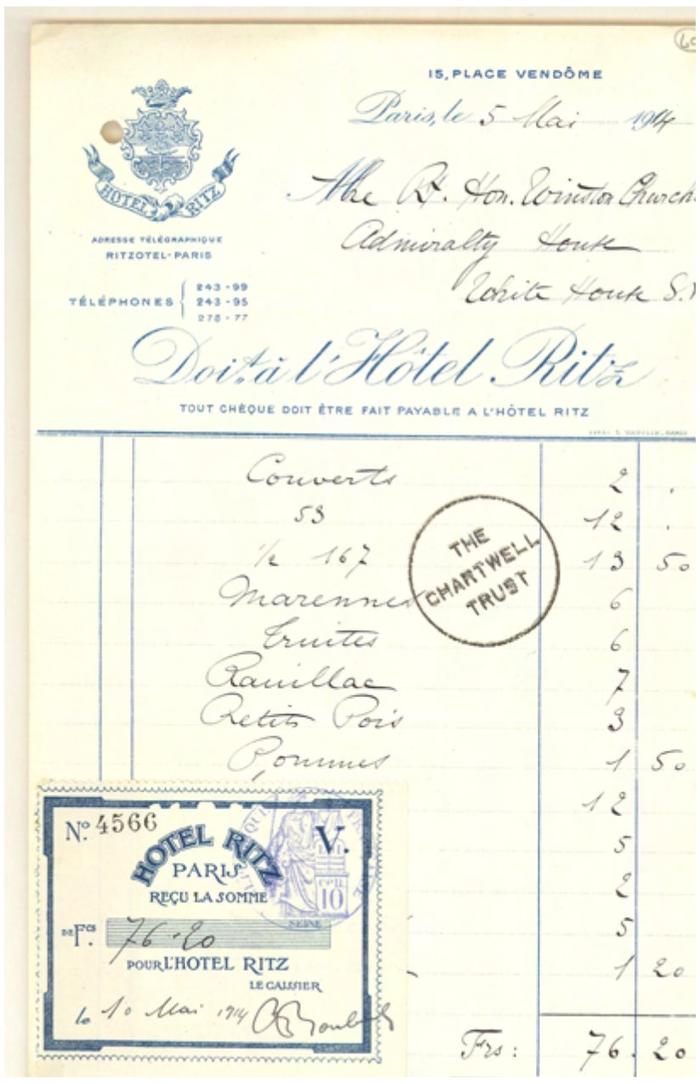

We have many menus covering much of Churchill’s long life. They reveal a preference for fine, well-prepared meals, consisting of plain food as that term was understood by his class in his day. Here are two such meals. On 5 May 1914, three months before the outbreak of the First World War, as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill dined at the Ritz in Paris, with one guest, and had the bill sent straight back to London to Admiralty House. Alas, the stamped receipt from the Ritz blots out the main courses but we can see that he drank a Paulliac and ate pommes and petit pois.

9

And, a year later, in May 1915, Churchill and one guest dined at the Carlton Hotel on truites, roast beef,

salade, pommes

and

compote

(the Carlton Hotel was badly damaged by German bombs in 1940).

Minutes and other chronicles also show Churchill’s

willingness

to make do with less when the circumstances required it. During the “Black Dog” days – as Churchill called his depression – after his resignation as First Lord of the

Admiralty

in 1915 following the Dardanelles setback, he tried to console himself as he wrote to his brother, Jack, from Hoe Farm where the family was living: “We live very simply – but with all the essentials of life well understood and well

provided for – hot baths, cold champagne, new peas and old brandy.”

10

New peas were a lifelong favourite and featured three decades later in the menu for the dinner party given by him at the Potsdam Conference.

Bill of fare, Paris Ritz, 1914

Of course, Churchill had his own definition of plain food, even under the trying circumstances of life at the front. In November 1915, Churchill wrote to Clementine from the trenches of the Western Front asking her to send him

every

week “a small box of food to supplement the rations. Sardines, chocolate, potted meats, and other things which may strike your fancy”.

11

Two months later, he reminded her to send him “large slabs of corned beef: Stilton cheeses:

cream: hams: sardines – dried fruits: you might almost try a big beef steak pie: but not tinned grouse or fancy tinned things. The simpler the better: & substantial too; for our ration meat is tough and tasteless …”

12

A month later he reported to Mrs. Churchill that during an attack “we

hastily

seized our eggs & bacon, bread & marmalade and took refuge”.

13

Not everyone would characterise the foods he asked be sent to the trenches as “the simpler the better” but we should remember the diary entry of Harold Nicolson, a

contemporary

and fellow member of the upper class, 25 years later, after lunching with the Churchills in their wartime flat, “We have white wine and port and brandy and hors d’oeuvre and mutton. All rather sparse.”

14

Not how we would understand the term.

Impatience with badly prepared foods came to the surface when Churchill, by then Prime Minister, was entertaining Molotov and other Soviet officials at Chequers. The Soviets’ schedule had been erratic and meals were often late or postponed indefinitely. At one dinner, quail was served but to the Prime Minister’s nose, they were not quite “right” and too dry. He was “displeased” and said to the caterer, “These miserable mice should never have been removed from Tutankhamen’s tomb.”

15

At more formal dinners, Churchill’s taste seems to have diverged even further from the plain food, well prepared, that he told his contemporaries he preferred. Of course, to someone born in Blenheim Palace, plain food would have meant something vastly different from what it means today,

or indeed even from what it meant to his contemporaries.

Churchill’s likes and dislikes were formed in rarefied

late-Victorian

and Edwardian society, in which diners of his social class were accustomed to multiple courses, and quite elaborate courses at that. And nothing in his girth or in his consumption of cigars and champagne suggests any

late-in-

life conversion to moderation. Norman McGowan, who cared for Churchill late in life, said he was “blessed with an excellent digestion and a lively regard for the pleasures and benefits of good food and wine. Not for him is the ascetic regime of so many famous men of advancing years”.

16

Aged 88, Churchill, having recovered sufficiently from a broken leg, attended a dinner of his beloved Other Club at the Savoy, where “the food and wine are remarkable”.

17

The chef proudly prepared what is reported to have been Sir Winston’s favourite dishes:

18

P

ETITE

M

ARMITE

S

AVOY

F

RIED

F

ILET OF

S

OLE WRAPPED IN

S

MOKED

S

ALMON AND

GARNISHED WITH

S

CAMPMPI

F

ILET OF

R

OAST

D

EER STUFFED WITH PÂTÉ DE FOIE GRAS

AND SERVED WITH TRUFFLE SAUCE

No dessert is mentioned. Few would call this plain food, and the accounts of other witnesses are not completely consistent with this chef’s view of what Churchill preferred at this late stage in his life.

With Anthony Eden, a private dinner consisted of “champagne and oysters in his bedroom”;

19

and with Field

Marshal Alanbrooke “a tête-à-tête dinner sitting in

armchairs

in the drawing room”, dining on “plovers’ eggs,

chicken

broth, chicken pie, chocolate soufflé and with it a bottle of champagne between us, port and brandy!”

20

Even under difficult circumstances, Churchill’s fare was very often a cut above the ordinary. When escaping from captivity in South Africa, he hid for two days’ living on two simple cold roast chickens, melon and whisky, a diet denied most fugitives.

It may well be that Churchill preferred to say, and perhaps even to believe, that “plain food” was his culinary choice

because

from at least the eighteenth century “the patriotism of plain cooking was one feature of Englishness”, with “the roast beef of old England … an emblem of solidity,

unyielding

to Napoleon’s batterie de cuisine”.

21

Claiming a

preference

for plain food, in short, was used by Churchill and his contemporaries to wrap themselves in the flag, to assure themselves that no matter how high their station, they had not abandoned their muscular Britishness for the more effete tastes of continental Europe. No drippy French sauces for a true Englishman. “The PM doesn’t like his chicken ‘messed about’,” affirms Lord Moran,

22

referring to Churchill’s

dislike

of devilled chicken.

But Churchill’s exposure to the troops in the field and their vastly different culinary backgrounds, together with his experience of wartime rationing, and advancing years did acquaint him with the virtues of simpler English fare. Lady Williams, a credible witness to his preferences during his second premiership, reports that his tastes ran to simple foods, and that among his favourites were jellied consommé, Irish Stew, and plain chicken. Lady Williams also relates that, after a long night, sometimes at two or three a.m., the Prime Minister would suddenly signal that her dictation (or to use

Churchill’s words, “take down”) chores were over by

hollering

“soup!” This meant that he wanted his customary

late-night

bowl of jellied consommé and that he was ready for bed. Indeed, Churchill seems to have had a more-than-average interest in soups, his preference for consommé matched by his aversion to cream soups.

Such a Churchill favourite was consommé that, in 1934, he formally asked the Ritz in Paris for its recipe and paid their invoice of 190 Fr. when it arrived. In 1938 he found confirmation for his preference from a doctor who suggested a diet that, among other restrictions, allowed “no soups except clear consommé”.

23

Colville, Churchill’s Assistant Private Secretary during the war, described a dinner he had with the Prime Minister and his daughter Mary:

The tastelessness of the soup so excited his frenzy that he rushed out of the room to harangue the cook and returned to give a disquisition on the inadequacy of the food at Chequers and the fact that the ability to make a good soup is the test of a cook.

24

Edmund Murray, one of Churchill’s bodyguards, provides another “soup!” story. Churchill was staying at the royal palace in Denmark after receiving an award from King Frederick IV of Denmark. Churchill’s regular valet had the night off so when he required his “soup!” there was no one to prepare the consommé. The story goes

that the King himself prepared the soup and served it to Churchill.

25