Read Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table Online

Authors: Cita Stelzer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II, #20th Century, #Europe, #World, #International Relations, #Historical, #Political Science, #Great Britain, #Modern, #Cooking, #Entertaining

Dinner With Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table (17 page)

Churchill was looking forward to meeting Truman.

They had exchanged many important cables and

spoken

on the phone since Truman had become President but had not met in person. After their first working meeting in Potsdam, Truman noted in his private diary that Churchill “is a most charming and clever person”. Perhaps unaware of Churchill’s deep admiration for the United States, he added that Churchill “gave me a lot of hooey about how great my country is. I am sure we can get along if he doesn’t try to give me too much soft soap”.

19

In his memoirs, Truman, knowing that he was writing for publication, recorded, less

controversially

,: “I had an instant liking for this man who had done so much for his own country and for the Allied cause.”

20

Truman and Stalin reflected their perceptions of the declining importance of Britain and its Prime Minister by meeting without him on the day before the formal meeting opened. On the morning of 17 July, Stalin showed up

unexpectedly

at Truman’s villa, with Molotov in tow. It was the first encounter of the American and Soviet leaders. Protocol was abandoned as they sat down to get acquainted. As time passed, a Truman aide slipped into the room and asked if the President wanted to ask his new friends to stay for lunch. The President asked what was on the menu. “Liver and

bacon

” was the reply. The President told the aide: “If liver and bacon is good enough for us, it’s good enough for them.”

21

Stalin at first said he could not stay but was persuaded to do so. After Stalin admired the wines served, Truman sent him “twelve bottles of Niersteiner (1937 vintage) wine, twelve bottles of Port wine and six bottles of Moselle wine as a gift”.

22

After lunch, when Stalin and Molotov had left, the President took a nap.

That afternoon Churchill, too, had a busy lunch. This one with Truman’s Secretary for War, Henry Stimson, who

told him that the Americans had successfully detonated an atomic bomb.

The following day, 18 July, Churchill invited Truman to lunch in his villa, before the next plenary session, due to start late in the afternoon. Churchill proudly noted the President called this lunch “the most enjoyable luncheon he had [had]for many years.”

23

From the Prime Minister’s point of view, it was also among the more useful: he had an opportunity to discuss with the President the implications of the successful detonation of the atomic bomb.

Attesting to the difficult nature of the issues

confronting

the leaders is the fact that many of the agenda items were the same as those with which they had wrestled at the Teheran and Yalta conferences: reparations; the borders and divisions of Germany; the future governance of Poland; the continuing war in the Far East; and the structure of a

long-anticipated

institution to preserve world peace.

There were official banquets at which each of the Big Three were hosts, as well as smaller working staff dinners every night (also breakfasts, lunches and teas). It was in these settings that Churchill hoped that not only he, but also his military and political staffs, would establish the

tripartite

personal relations that would carry through to broad agreements on the agenda items, and to post-war

cooperation

. At Truman’s official dinner on 20 July, the President again served those wines that Stalin had praised, along with a well-known claret, Mouton d’Armailhacq, and a Pommery champagne 1934.

The celery, lettuce, tomatoes and ice cream were flown into Babelsberg from the USS

Augusta

berthed at Antwerp. Other courses, presumably provided locally were pate de foie gras,

caviar on toast, vodka, cream of tomato soup, perch sauté meuniere, filet mignon with mushroom gravy, shoestring potatoes, lettuce and tomato salad, French dressing, Roca cheese, vanilla ice-cream, chocolate sauce, demi-tasse …

24

Truman, who loved classical music and played the piano very competently, and as often as possible, asked Stalin to name his favourite composer. Stalin replied, “Chopin” – a Polish freedom-loving émigré who spent most of his adult life in France, and a composer who probably would have been Gulag-bound, or worse, if he had lived in Stalin’s time. The President therefore arranged that a classically-trained piano-playing US Army sergeant, Eugene List, would begin the musical entertainment with one of his personal

favourites

, the Chopin Waltz in A Minor (Opus 42).

25

Sixteen years later, during the festivities for President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, President Truman was a guest at the White House and Eugene List played Truman’s favourite Chopin waltz again.

26

Stalin so enjoyed the performance that he shook the sergeant’s hand warmly afterwards. Cadogan joked with Molotov that they should hire Sergeant List to play while they discussed the Polish Question.

27

Churchill was less impressed: his taste ran more to the gaiety of Gilbert and Sullivan, and music hall ditties, hummable tunes and

martial

airs. It would be interesting to know the reaction of Molotov, who it is said, played the violin well enough to busk in the early days before he rose to power with Stalin.

28

Not to be outdone, Stalin, for his own banquet the

following

evening, 21 July, rushed in four musicians from Moscow, including two female violinists whom Truman describes as “rather fat,”

29

and, in a letter home to his wife Bess, “a

dirty-faced

quartet”.

30

Churchill undoubtedly would have preferred conversation, but it was not to be. President Truman told the Prime Minister he would be leaving the dinner as soon as “our host indicates the entertainment is over”.

31

As did Churchill who once quipped: “I stay until the pub closes.”

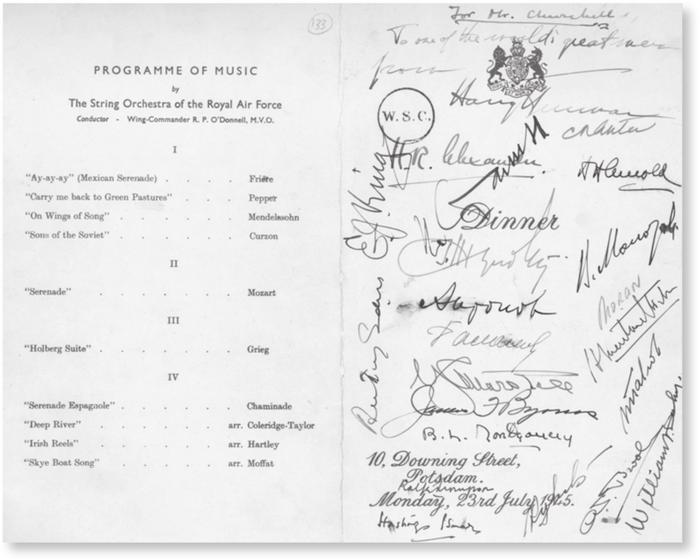

Not long after Churchill returned to his villa that night, a directive went out for entertainers for the dinner party he planned to give: “He ordered up the whole of the Royal Air Force Band – the String Orchestra”.

32

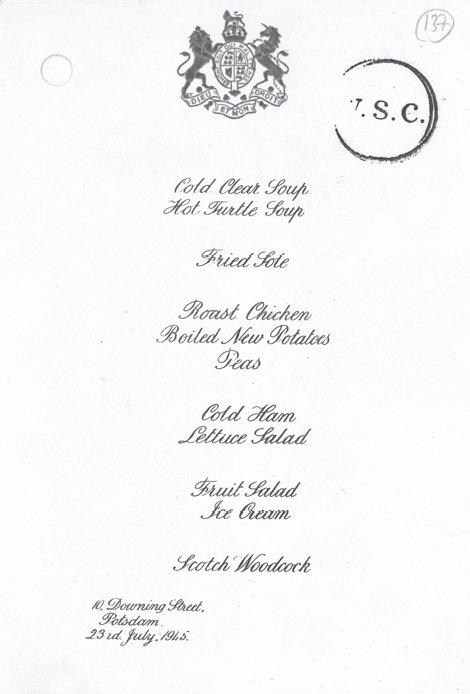

Organising an

emergency

flight from London was no easy matter for those in charge of logistics, but the Prime Minister was determined to have his dinner party go well. Besides, he had, for some reason, decided to add a ham course to the proposed menu so that, too, had to come by air from London.

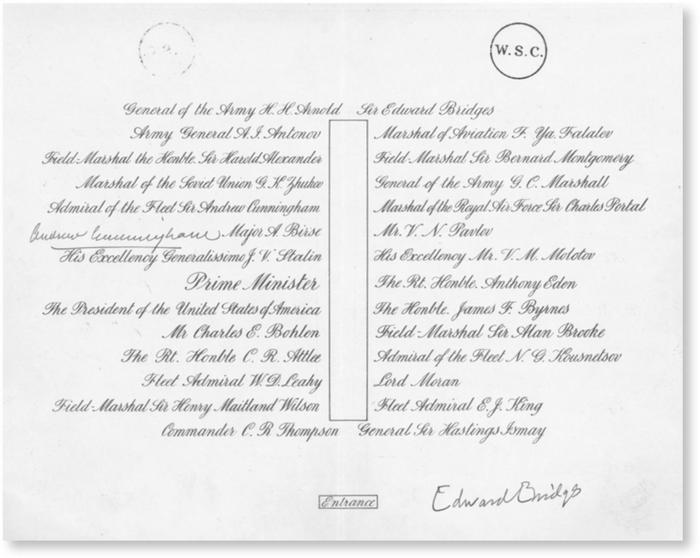

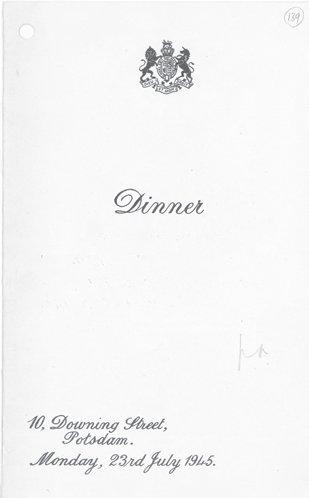

The seating plan and programme for Churchill’s banquet on 23 July were important enough to him to be pasted into the Churchill family albums – now called the Broadwater Collections – with the following note, in bold capitals, to his then-secretary Elizabeth Layton:

THIS IS THE CARD OF THE “BIG THREE” DINNER

AT POTSDAM 23-7-45 AND MUST BE

CAREFULLY PRESERVED IN MR. CHURCHILL’S

SCRAP BOOK PLEASE

Churchill first had to decide how many guests he could invite. So important did he consider the physical comfort of a dinner to be that he ran a test: he had some of his staff sit around the table and pretend to be Stalin or Truman – to

make certain the elbow room was adequate.

33

He calculated that he could fit only 28 at a table that had been hastily

constructed

by the sappers, so he was required to recall several invitations, including one to the Solicitor General, Sir Walter Monckton. Comfort and space, Churchill felt, would ease the flow of conversation. Churchill himself arranged the seating.

On the morning of 23 July, the Prime Minister began to fret about the dinner plans. Moran tells us that Churchill felt “that he has discharged his duty as host if he provides good plain fare and gives his guests plenty of elbow room to get at it”.

34

But for whatever reason, the Prime Minister that morning upset the pineapple juice on the table by his bed. He gruffly ordered his valet, Sawyers, out of the room even though the clean-up was not finished. Some of his tension might have come from his anticipation of the upcoming

dinner

, which he regarded as the most important of the

conference

. His tension might also have been caused by three

additional

facts. First, he worried about how and when to tell Stalin of the successful testing of the new atomic weapon. Second, by this stage in the conference, Churchill was aware of the earlier attempts by Stalin and Roosevelt – continued at this conference by Truman – to marginalise him. His dinner was, in a sense, an attempt to regain standing and control of events. Third, the dinners that preceded his had gone

reasonably

well, setting a standard Churchill felt he had to match or, better still, exceed.

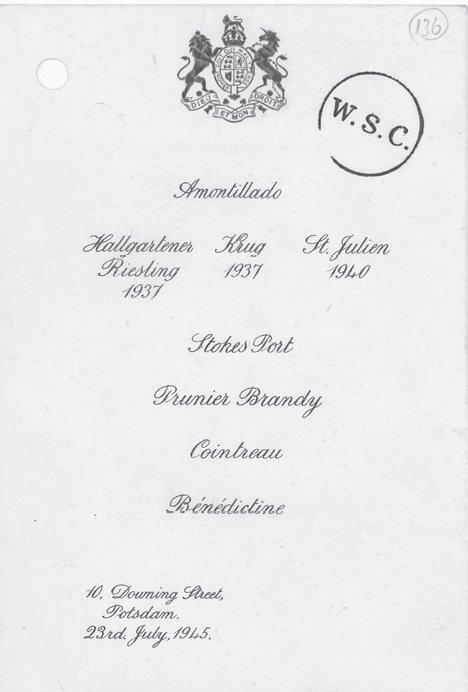

The assembling diners, sipping either the 1937 Krug or the alternative offering of amontillado, must have been

surprised

to hear the string orchestra of the Royal Air Force strike up Freire’s Mexican Serenade, “Ay-ay-ay”. Truman later recalled: “I liked to listen to him [Churchill] talk. But

he wasn’t very fond of music – at least my kind of music”,

35

which was the classical music the President had played a few nights earlier at his own dinner.

Churchill’s dinner, Potsdam Menu, music, wines, seating chart