Divine Fury (45 page)

Authors: Darrin M. McMahon

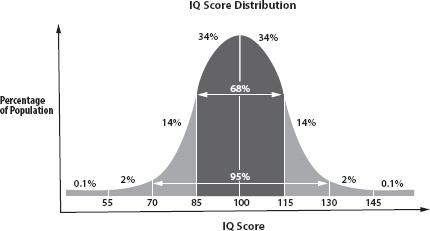

FIGURE 5.10.

The IQ scale. Extrapolating from the work of earlier statisticians, Francis Galton suggested that intelligence, like other characteristics in a population pool, should follow the contours of a Gaussian distribution, or “bell curve,” an insight that was critical to the later elaboration of the intelligence quotient (IQ). Here, IQ is plotted to show its natural variation, with only 2 percent of populations achieving scores over 130, and only 0.1 percent over 145.

FIGURE 5.11.

Auguste Joliet,

The Genius of Destruction

, 1872, after a design by François Nicolas Chifflart. The nineteenth century gave new sanction to the old links between genius, evil, destruction, and crime.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

.

FIGURE 6.1.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck,

Ode to the Genius

, 1917. A fallen angel, or

genius

, is prostrate before a work of art, in search of redemption. Note the streaking comet, symbol of genius, in the background.

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, New York

.

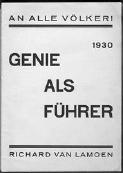

FIGURE 6.2.

The genius as leader. A writer and chairman of the Dusseldorf Society for Culture, Lamoen argued in this short work that “the genius is the highest form of humankind and his destiny is to lead the people.”

Bpk / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin / Dietmar Katz / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 6.3.

Genius by association. As part of his effort to present himself in the “brotherhood of genius,” Hitler made strategic pilgrimages to key German sites. Here, he contemplates Fritz Röll’s bust of Nietzsche at the Nietzsche Archives, the house in Weimar where the German philosopher died. When Hitler visited in 1934, he was greeted by the philosopher’s eighty-eight-year-old sister, Elizabeth Förster Nietzsche, an ardent Nazi supporter.

Klassik Stiftung, Weimar, Goethe-Schiller Archiv 101/239

.

FIGURE 6.4.

Hitler, high above the angels, paying homage with his staff to the genius of Napoleon at his tomb in Paris, June 1, 1940.

Keystone / Hulton Archives / Getty Images

.

FIGURE 6.5.

The cover of a film program of one of the Nazis’ many “genius films,”

Friedrich Schiller: The Triumph of a Genius

(1940), which celebrated the German poet’s refusal to submit to ordinary laws. The film contains the line “The Genius . . . is not just born of his mother, but of his whole people.”

Bundesarchiv, FILMSSG 1/4782

.

FIGURE 7.1.

A piece of genius. A microscopic slice of Einstein’s brain.

Miguel Medina / AFP / Getty Images

.

FIGURE 7.2.

The marriage of business and genius. Henry Ford and his friend Thomas Edison.

Culver Pictures / Art Archive at Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE 7.3.

A contemporary religion of genius. The twentieth-century Vietnamese religion Cao Dai venerates the French writer Victor Hugo as one of its three founding fathers. Other revered figures include Napoleon, Shakespeare, Descartes, Tolstoy, Julius Caesar, and Thomas Jefferson. Hugo is shown here (center) in a painting at the Great Temple at Tay Ninh, Vietnam.

Jean-Pierre Dalbera

.

Segalin’s utopian scheme to establish an Institute of Genius was never realized. But even though Vogt would have somewhat better success as an institutional founder, it was the same deep interest in the eugenic improvement of humanity and the related fascination with genius that best explains Vogt’s invitation to Russia in the early, heady days of the Revolution. Lenin’s brain was a prize specimen in itself, but it also had the potential (or so it seemed) to reveal mysteries about genius that would be crucial to the advance of human progress. Vogt wasted no time. In February 1925, he, his wife, and a small team of assistants began the arduous process of analyzing and dissecting the brain, which they eventually sliced into more than 30,000 specimens. Meanwhile, Vogt set

to work drafting a proposal, with Semashko’s support, for the establishment of a brain research institute with a much wider mandate to study cerebral architectonics in conjunction with human race biology. Created and granted funding in 1926 on the personal approval of Stalin, the V. I. Lenin Institute for Brain Research, or, as it was more commonly known, the “Moscow Brain Institute” (Institute Mozga), was officially opened the following year in a lavish mansion expropriated from an American businessman. Under Vogt’s directorship, the institute continued work on Lenin’s brain as well as on the brains of “renowned revolutionaries” and other “significant Russian public figures.” It also served as the site of an extraordinary collection, the so-called Pantheon of Brains, which gathered together the vital organs of prominent Soviet artists, scientists, and politicians. Part museum and part “Bolshevik Valhalla,” the pantheon was a public attraction, displaying replicas, casts, and photographs of the brains of leading revolutionaries along with detailed descriptions of their achievements. In the very same building, technicians worked diligently on the actual brains themselves, ensuring that in death, as in life, these highly evolved organs would continue to serve the revolutionary cause.

21