Dog Sense (42 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

The odors in question evidently originate at both ends of the body. Sniffing is often focused around the ears, indicating that these may be the source of an individual-specific odor. But although the ears definitely

contain odor-producing glands, little is known about what kind of information is contained in the odors they produce. Sniffing under the tail must pick up odors from the preputial (male) and vaginal (female) glands that add their contributions to the dog's ubiquitous urine-marks.

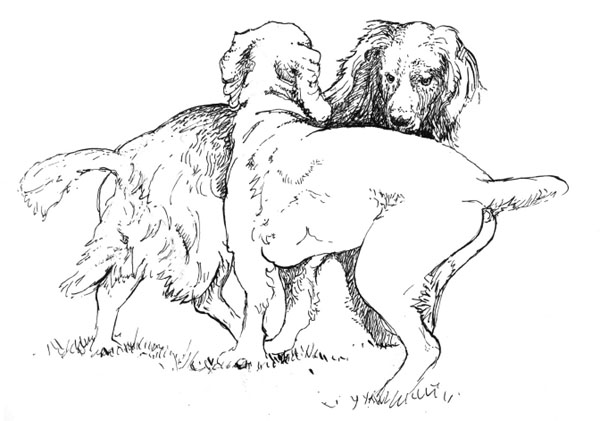

Because each attempts to sniff the other first, the two dogs often end up circling one another

However, the main target of canine sniffing seems to be the anal sacs. Located on both sides of the anus, as their name implies, these contain a pungent mixture of odors (mainly produced by microorganisms) that varies considerably from one individual dog to another. Perhaps because the anal sacs are usually closed, their odors don't vary much from one week to the next, though they do change gradually over time-scales of a few months or so.

10

They are therefore good candidates for a “signature” odor, albeit one that will, like all chemical signals produced by mammals, require relearning by recipients as it changes gradually over time. This is presumably part of the explanation for dogs' insistent attempts to sniff the back ends of every other dog they meet; if the odor stayed consistent from one month to the next, they'd need to do it only very occasionally. Such sniffing, like urine-marking, has origins that go back to before domestication. Young male wolves have a similar fascination with sniffing

this part of the body, and adult wolves sometimes actively invite other members of the pack to sniff them in this area, by standing stock-still with their tails held upright.

Scent inspections tend to follow predictable patterns. Some dogs, mostly males, go straight for the area under the tail, which produces an information-rich odor. Most females, and a few males, prefer to sniff the head of the other dog first, and then to move backâprovided the other dog will let them. This difference between the sexes is thus far unexplained, but it is also true of wolves, so it may simply be an inherited tendency with little functional significance as far as modern dogs are concerned.

Interestingly, while dogs love to sniff other dogs, it seems that most dogs don't much like being sniffed themselves. It is almost always the dog

being

sniffed who attempts to break off the interaction. Thus while dogs want to find out as much as they can about other dogs' “odor signatures,” they seem reluctant to give away their own. (Young wolves share this reluctance, so this may be where the behavior originated.) It's as if they see information about the dogs around them as the key toâwell, somethingâsince once the sniffing is finished the interaction usually ends. What that “something” is has yet to be resolved. If they're successful in their encounters, dogs go home from walks with lots of information in their heads about what the other dogs in their neighborhood smell like. What they do with this information is currently unclear.

In fact, there is a great deal we don't know about the kinds of information dogs can get by sniffing each other. The anal sac may signify more than individual identity; for example, for a wolf it might also indicate which pack it belongs to, if members of a pack share an odor. Some components of the wolf's anal sacs may also vary according to gender and reproductive state. The same might be true for dogs, but at present we don't know.

It's remarkable that we know so little about the one activity, sniffing, that dogs like to do the most. Nothing better exemplifies how human-centered we can be when thinking about our domestic animals. Somehow we fail to grasp the “otherness” of much of what they experience.

Of course, to dogs what something smells like is not “other”; it is, if anything, more important than what it looks like.

The dog's fascination with odor must have originated way back in its evolutionary past. Scent is a major mode of communication for a wide variety of animals (it is humans who are the exception, not dogs). In particular, scent is a good way of transmitting information between animals that live far apart from one another. The early carnivores, the dog's remote ancestors, are very unlikely to have lived in groups. They were almost certainly solitary, defending territories against other members of their own kind. The only groups would have been mothers and their dependent young, who would have stayed together for a few months at most before the young were old enough to disperse. Communication between adults would therefore have revolved around establishing and maintaining territorial boundaries. Apart from courtship and mating, face-to-face meetings would have been a rarity. Not only that, they would have been risky: Being well-armed with teeth and claws, carnivores try to avoid disputes that damage both parties, not just the loser. Finally, these animals were probably nocturnal, inhibiting visual communication. In the natural world, all these issues can be circumvented by using scent-marking as the primary mode of long-distance communication. A scent-mark designed for that purpose can last for days. Messages can be left for recipients to pick up at some undetermined moment in the future, obviating any necessity for actual meetings to take place. Contemporary dogs, who evolved from sociable animals and have become yet more sociable with domestication, may no longer need to scent-mark as frequently as they obviously think they do; but their wild ancestors must have found it very advantageous, and their legacy remains in our dogs' everyday behavior.

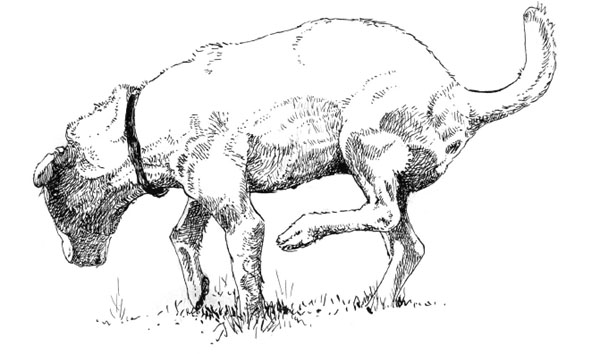

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the dog's apparent obsession with depositing small quantities of urine as scent-marks. Male dogs are renowned for their raised-leg urinations, but females also urine-mark routinely: Although they usually squat to urinate, many also use a “squat-raise” marking posture. It's not entirely clear why females leave scent-marks; one clue may be found in the observation that bitches in

Indian villages squat-raise around their denning sites. The male dogs in the same villages perform their characteristic “raised-leg urination” everywhere, but especially at the boundaries of their family-group territories.

11

Male wolves, particularly breeding males, also mark at territorial boundaries and along frequently used paths, presumably as a way of communicating with other packs nearby.

“Squat-raise” urine-marking

The domestic dog's passion for “pee-mail” can therefore be traced back through its immediate ancestor, but this does not explain why pet dogs do it so enthusiastically today. Perhaps they would like to “own” the area where their owners take them for exercise; however, because they have to share this with other dogs and their access is time-limited by their owner, they get caught up in a vicious cycle. Every time they go out, they find that the scent-marks they left yesterday have been overmarked by other dogs. So they have to mark again to reestablish their claim to ownership, and so on and so on.

Scientists still do not know precisely what message is contained in each urine mark, but it seems highly likely that dogs' urine carries an odor that is unique to each individualâone that can be memorized by others. It is also likely that in male dogs this unique odor contains contributions from the preputial gland as well as from the urine itself. What

is less clear is how much other information is conveyed. For example, can a dog tell how large, how old, how hungry, how anxious, how confident another dog is, simply by sniffing its scent-mark? We cannot yet answer this question, but we do know that the main message carried by a bitch's urine, apart from her identity, comes from the vaginally produced scents that indicate the status of her reproductive cycle. Bitches who are willing to mate produce a powerful pheromone that can attract males from long distances. (Pheromones are chemical signals that are similar in all individuals of a species.) However, scent does have one serious flaw as a communication mediumânamely, that the message itself is very hard to control. Mammalian scent-signals are mainly produced by specialized skin glands. These glands inevitably get invaded by microorganisms, which alter the scent by adding metabolic products of their own, which can be pungent. If you had a nose as sensitive as a dog's, it would be like putting up a notice in front of your house where graffiti artists come along at unpredictable times and progressively alter whatever is on the sign, including obliterating your own name.

Some animals, dogs included, have handed over responsibility for producing the smell to the microorganisms themselves. For example, bacteria on the mother's skin make the odor that newborn puppies use to orientate toward their mothers. Likewise, the anal glands of both male and female dogs (and many other carnivores) secrete a mixture of fats and proteins into the anal sacs to which they are attached, allowing the bugs to turn these into the more volatile chemicals that make up the odor itself. (Scientists have shown that if antibiotics are injected into the sacs, killing the microorganisms, the secretion becomes almost odorless.) The “graffiti artists” can now write what they like, but they can use only the “colors” (fats and proteins) they're given; thus the dog retains an element of control.

Such an odor is, however, both arbitrary and ever-fluctuating, placing limits on its usefulness. It is impossible to predict what it will smell like in advance, so if it is to be of any use in transmitting information, recipients will first have to learn what it means, and then relearn whenever it changes. Scent-marks that are intended to claim ownership of territory present an additional problem, since the whole point of them is

to permanently identify individuals who are absent. If the odor of an owner's scent-mark changes from one week to the next, an intruder may mistakenly deduce that ownership of the territory has recently changed when in fact it has not.

A territory-holder can overcome this drawback by occasionally actually meeting his neighbors, thereby giving them the opportunity to make the connection between his appearance and his scent. If that scent is changing subtly over time, then those meetings need to be frequent enough for the connection to be maintained. This behavior is known as “scent-matching”; widespread in rodents and in antelope, it is less widely studied in carnivores, and not at all in dogs, despite there being every indication that they must be doing something like it.

Making and reinforcing the link between odor and appearance seem to be uppermost in many dogs' minds whenever they meet, suggesting that dogs do engage in a type of scent-matching. Specifically, it's likely that they memorize the odors of all the dogs they meet (Why else go to the trouble of all that sniffing?) and then compare these with all the indirect information that they get from sniffing scent-marks while they're out on walks. If they don't find any match, then they may assume that the other dog lives far away; if they find a lot of matches, then the dog must live nearby. Since scent-matching is usually connected with territorial behavior, perhaps domestic dogs perceive public parks and streets as a vast “no-man's-land” between territories, always worth checking for occupancy in case they ever get the chance to live there.

Left to their own devices, many dogs prefer to use their sense of smell even when vision would appear to be more efficient. Trained explosives search dogs always prefer to use their noses rather than their eyes, even in cases where visual cues might lead them to their target more quickly. However, dogs are also very flexible in their behaviorâand pet dogs quickly come to realize that we humans are much more attuned to visual cues than to olfactory ones. As a result, dogs can be successfully fooled into choosing an empty bowl rather than a bowl full of foodâsimply by having the dogs' owner point to the empty one.

12

Normally, of course, the dogs could have quickly identified the full bowl from its

smell. This exemplifies the high priority that dogs put on social information, and also how well-adapted they are to attending to the ways we, as well as they, communicate.