Dog Sense (5 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

A family of coyotes

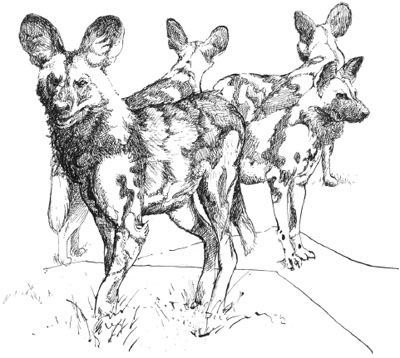

Finally, our journey takes us to Africa, the birthplace of our own species and an area in which domestication would therefore seem highly plausible. This continent is rich in canids, including four species of jackal (the golden jackal among them) as well as the African wild dog, undoubtedly a rival for the grey wolf's claim to be the most sociable of the canids. The African wild dog's packs are larger than the wolf's; up to fifty individuals have been seen hunting together, although the typical number of adults in a pack is eight. In the open grasslands, which the African wild dog favors, cooperative hunting is essential for survival. Only a pack can defend kills against other large predators, such as lions and hyenas. (Not that African wild dogs are particularly small themselvesâthey are the size of a small German shepherd, but with a brindled coat and huge upright ears.) After they have made a kill, the food is shared amicably between all pack members; if there are cubs back in the den, each dog will eat more than usual and regurgitate some to feed the young upon returning home.

A pack of African wild dogs

For most of the year, relationships between the members of a pack of African wild dogs are friendly. Every morning and evening, they engage in a greeting ritual, running around excitedly, thrusting their noses into each others' faces (a mimicry of the begging behavior that they used when they were cubs), and producing a squeaking noise that makes them sound more like a troop of monkeys than a pack of dogs. Once the adults have become sufficiently hyped up by all this chatter, they run off together on the hunt. Pack members will occasionally quarrel with one another, but serious fighting is rareâuntil one of the females comes into season. When she is ready to mate, the dominant female becomes seriously aggressive toward the other adult females, and it is not unknown for her to inflict serious injuries on them. As a result, she usually is the only female in the pack to produce a litter each year; if one of the other

females also produces a litter, the dominant female may try to kill her cubs, though sometimes all the cubs get mixed up together and both mothers look after them.

Despite this occasional violence within groups of African wild dogs, the high level of cooperation in wild dog packs suggests that they should be easy to domesticate. For example, they have a complex vocabulary of vocalizationsâtwitters, begging cries, gurgles, yelps, squeals, whimpers, whines, moans, “hoo”s, growls, and barks that would seem ideally suited for communication with such a vocal species as ourselves, far more so than the rather taciturn wolf. Yet there seems to be no evidence that any attempt was ever made to domesticate this species. Considered in the broader context of domestication as a whole, however, this failure may be less surprising. Despite mankind having evolved in Africa and therefore having a much longer history there than anywhere else, almost all the significant domestications of animals have taken place on other continents. It's been suggested that the human race needed to get outside its evolutionary “comfort zone” before becoming sufficiently motivated to domesticate animals (or indeed plants). Perhaps the African wild dog was simply in the wrong place to become part of our world.

While the histories of the canids vary from place to place and species to species, two of the dog's distant cousinsâthe golden jackal and the South American culpeo foxâprovide tantalizing glimpses of domestications that seem to have begun but were never completed. Each occurred on a different continentâone in Eurasia, the other in South Americaâand in very different societies. This points again to the importance of the 5-million-year-old canid “toolkit”âflexible sociality, a good nose, expertise in huntingâas being the key to the suitability of canids for domestication. And yet neither of these experiments in domestication was, in the long run, successful.

Domestications occur only when a human need meets a suitable species, assuming that the need is backed up by sufficient resources. Such conditions seem to occur very rarely, as attested by the tiny number of mammalian species that mankind has fully domesticatedâa number that barely scrapes into double figures. It seems entirely possible that all the species discussed so far could have been domesticated, except

that the conditions for domestication were never as ideal, or could not be sustained for as long, as those of the domestic dog.

Finally, we must turn to the grey wolf, as the only one of the canids to have been domesticated successfullyâif by successfully we mean surviving into the modern world. Indeed, the domestic dog is very successful: The 400 million or so dogs in the world outnumber wolves over a thousandfold. A few hundred years ago there were probably only about 5 million wolves in the world; today there are only 150,000 to 300,000. If we set aside the artificial distinction of “domestication” for a moment, we could say that the wolf has evolved into the dog, leaving behind a few, highly totemic vestiges of its past that hang on by a thread in the wild. Some wolves were able to take advantage of man's domination of the globe, and became dogs. Others were not, and stayed wolves.

No account of dog behavior can afford to ignore the wolf, if only because many books on dogs place such emphasis on the dog's wolf-like natureâbut wolves themselves have, as it turns out, been fundamentally misunderstood. A great deal has been written about the grey wolf, but much of that is either misconceived or at least unhelpful when it comes to understanding the behavior of modern domestic dogs. In the past, the wolf has been portrayed as the quintessential pack animal, and its packs have been portrayed as being essentially despotic, rigidly and aggressively controlled by an “alpha” pair. Logically, therefore, as a descendant of the wolf, the dog was thought to be the same under the skin, undoubtedly less aggressive in nature but nevertheless born with the expectation that it must eventually seek to “dominate” all those around it, canine and human alike. The past decade has seen a radical reappraisal of the wolf pack, howeverâregarding both how it constructs itself and the evolutionary forces that drive it. Our conception of the dog is therefore overdue for revision. If wolves are not despots, as we now know, then why should we assume that domestic dogs are impelled to take control of their owners?

Like most other canids, grey wolves are highly social animals and have a strong preference for living in groups. This is not to say that individuals do not live alone from to time to time, but it is not usually from choice. A lone wolf may have been driven out of its pack, or may have been forced to forage on its own when there was not enough food available to feed two wolves traveling together. But wherever possible wolves try to live together. Even wolves that scavenge from garbage dumps do so in groups, usually with between three and five members. (The wildcat, the domestic cat's ancestor, has also occasionally been observed feeding on rubbish, but always alone.) It's undoubtedly this thirst for company that, among other factors, made it possible for wolves to be domesticated.

A family of grey wolves

Although they are fundamentally sociable animals, wolves are also remarkably adaptable when it comes to their living arrangementsâanother trait that, perhaps even more than sociability itself, makes them especially good candidates for domestication. Wolves come together when local conditions permit and go their own ways in times of adversity. They can live alone or in small groups; when conditions are right, larger groups comprising six to ten adults can form. As a rule, these larger groups occur only where the main prey available is also largeâtypically moose, caribou, or bison. Although a solitary wolf could probably kill a

caribou, especially one that was old, young, or sick, the wolf would risk getting injured itself, and would thus be more apt to seek smaller, less dangerous prey. Pack hunting is most likely a safer and more efficient way of hunting large animals, but this appears not to be the key to why packs can exist. What is probably more important in determining the formation of large packs is that a kill of one of these large animals provides far more food than a single wolf could consume. In summer, when alternative prey is often available, these larger packs tend to fragment into smaller units, perhaps coming back together again in autumn. It is flexibility such as this that's now seen as a second crucial factor allowing wolvesâa few of them, at leastâto adapt to living with humans.

The nature of wolf packs is crucial to understanding the social behavior of wolves, and thus the behavioral inheritance of domestic dogs, but until recently wolf packs have been wrongly thought of as competitive organizations. It's now known that the majority of wolf “packs” are simply family groups. Typically, a solitary male will pair up with a solitary femaleâeither or both will most likely have recently left a packâand raise a litter together. In many species the young leave or are chased away when they are old enough to fend for themselves, but not so in wolves. Provided that no one is starving, the cubs may stay with their parents until they are fully grown. Once they are experienced enough, they will participate fully in hunting, and thus a pack emerges. Often the younger members will still be part of the pack when the next litter of cubs is born and will help their parents to raise their brothers and sisters, bringing food back for them and babysitting them when the other members of the pack are out hunting. Contrary to many notions of wolf behavior, cooperation, not dominance, seems to be the essence of the wolf pack.

Modern biology demands explanations for the seemingly selfless behavior exhibited by the younger adult wolves operating within a pack. Logically speaking, a gene that influences one animal to help another to breed should die out, since it will be the animals not carrying the “unselfish” version of the gene who will leave the most offspring. Cooperative breeding must therefore have long-term advantages that outweigh its disadvantages. Biologists have been arguing for the past five decades about what the finer points of those advantages might be and

how they are expressed, but the theory of kin selection, first proposed in the 1960s, accounts for why cooperative breeding is much more likely to occur in families than in random assemblages of individuals.

By ascribing a benefit to the cooperation observed within wolf packs, scientists have been able to use the theory of kin selection to make sense of behavior that would otherwise be unintelligible. Offering cooperation to an unrelated animal carries risks, even in animals as smart as wolves; there is a danger, after all, that the favor may not be returned. On the other hand, performing a favor for a close relativeâsay, a son or a daughterâhas genetic advantages; even if that favor is never returned, the helper is still promoting the survival of some of his or her own genes, specifically those versions that are identical in the relative. (In a son or daughter there would be a 50 percent overlap, the other half coming from the other parent.) This advantage does not seem sufficient to promote lifelong abstinence from breedingâthe only mammals that exhibit such abstinence are naked mole-rats, which burrow beneath harsh deserts where a single breeding pair is unlikely to survive for long, even with the others' help. Nevertheless, kin selection does seem to be powerful enough to sustain temporary abdication from breeding, making it worthwhile for offspring to help their parents until the family group gets too large to sustain itself and the offspring leave to start families of their own.