Dog Sense (9 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

The absence of dogs in known burial sites older than fourteen thousand years almost certainly means that dogs were, before then, rather rare. If the culture represented in this group grave in Russia had used dogs for hunting, it seems likely that there would also be evidence of dogs in this or similar gravesâeither bones or, as with the horse, some kind of representation. That there are no such traces indicates that the society from which these people came did not have domestic dogs. If they had, these dogs' remains would probably have been indistinguishable from those of wolves; but in fact there is no trace of any wolf-like animal, domestic or wild, in the Russian group grave, even though wild wolves would almost certainly have been in the vicinity. Indeed, very few graves hold traces of ancient wolves.

Unlike dog burials, which, as noted, were quite common after they first appeared in the archaeological record, wolf burialsâwhether alone or accompanying human burialsâseem to have been extremely rare throughout ancient human history. (If common, they might have provided evidence for the early stages of domestication, when the bones of

proto-dogs would have been indistinguishable from those of wolves.) Wolf teeth do feature, alongside those of other predators, in many burials of humans, but their significance is usually unclearâand, in any case, many probably came from animals that were killed for their pelts. The close emotional relationship that hunter-gatherers evidently had with the animals they hunted seems not to have been extended to their competitors in the hunt, including wolves. Thus there is very little archaeological evidence indicating any kind of relationship between hunter-gatherer humans and wolvesâeither wild animals or those already on the path toward domesticationâuntil dogs suddenly appear in burials some fourteen thousand years ago.

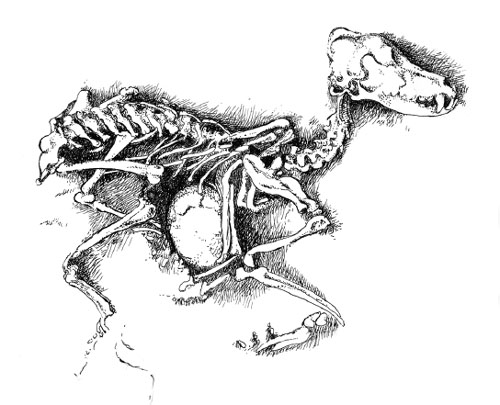

Among the very few wolf burials that have been discovered, one is particularly odd and may provide evidence for the transition from wolf to dog. Russian archaeologists recently found, in a cemetery near Lake Baikal, what they identified as a wolf buried with a human skull between its paws. The burial probably dates from only about 7,500 years ago, by which time there may well have been dogs in this area. What is remarkable about this wolf is that it was not local; it appears to be a tundra wolf and, if so, must have traveled several thousand miles before ending its days in this grave. But what if the animal is not a wolf at all?

A wolf burial near Lake Baikal in Siberia; its limbs enfold a human skull.

Rather than a far-flung tundra wolf, the wolf buried near Lake Baikal is, I believe, more plausibly the descendant of a “socializable” tundra wolf that had been adopted, many generations before, as a pet. Under this interpretation, such a burial gives us a tantalizing glimpse of the process of domestication in action. Domestication is very unlikely to have involved a steady transition from one group of wolves to today's dogs; on the contrary, it appears to have been a haphazard process in which several domestications occurred, in different places and at different times. The “wolf” in the grave may in fact be a proto-dog, the product of a late attempt at domestication in the frozen north, brought south, where it lived and died alongside its more “domesticated” cousinsâthe progeny of earlier domesticationsâwho, by then, were recognizable as dogs.

Archaeologists have found a few other burials of “wolves” that may in fact be proto-dogs. For example, 8,500 years ago in what is now Serbia, a small type of domestic dog was used for food, as attested by the many broken leg-bones and skulls found in rubbish pits there. Another (larger) type of dog from the same area and at about the same time was buried unharmed in proper graves, implying a role that included companionship. Even more pertinent, however, is evidenceâfrom the same location and periodâof the remains of what appear to be wolves. These may have been wild, but it is also possible that they were a third type of dog, which, unlike the other two, had not changed much in appearance from its wild ancestor.

Few traces of proto-dogs have been found in human burials, but is there anything in the fossil record to support the idea of gradual and haphazard domestication? Until recently, archaeologists were reluctant to identify wolf skulls more than fourteen thousand years old as belonging to anything other than a wolf, so any proto-dogs that were found were not labeled as dogs. The earliest distinct dog skull, from Eliseevich, in the Russian plain, was excavated from the edge of a pile of mammoth skulls, and it, too, has been dated to about fourteen thousand years ago; roughly the size of a husky's skull, it seems to have been buried accidentally rather than deliberately. However, three new skulls have recently been found that are intermediates between those of wolves and early dogs such as the Eliseevich dog. All three are very similar to today's Central Asian shepherd dog (although of course skulls cannot tell us anything about the texture or color of the dog's coat). The oldest of these skulls, from Goyet in

Belgium, is a staggering thirty-one thousand years old, more than twice the age of the oldest dog burial. The other two, from the Ukraine, are probably only about thirteen thousand years old, roughly contemporary with the first dog burials. The Goyet specimen is therefore something of an anomaly. Could it have been a direct ancestor of today's dogs? Or is it our only record of a very early domestication of the wolfâone that failed, hence the absence of any trace of dogs for the next seventeen thousand years?

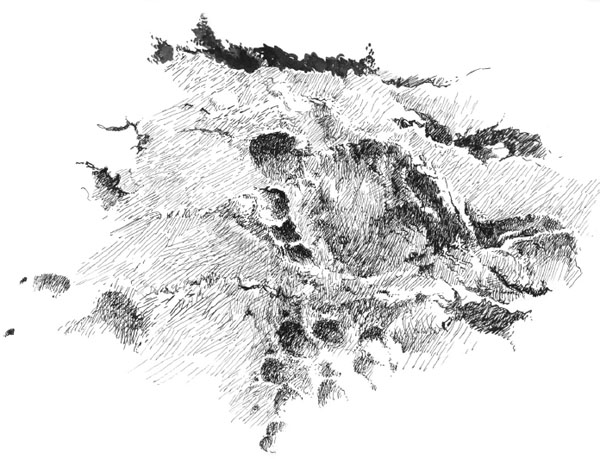

There is one more small piece of evidence that suggests a relationship between man and dog going back more than twenty thousand years. Deep in the Chauvet cave in the Ardèche region of France, which is famous for its prehistoric art, a fifty-meter trail of footprints made by an eight- to ten-year-old boy, alongside those of a large canid, hints at a close relationship between the two. The footprints of the canid are intermediate between those of a dog and a wolf. Soot from the torch that the child was carrying date the event at twenty-six thousand years ago, making these probably the oldest human footprints in Europe. With a little imagination, one can picture a boy and his faithful (proto-)hound, venturing into the cave to view the spectacular representations of wild animals painted on its walls.

Evidence such as the foregoing is, ultimately, too flimsy to give us a firm idea of when or where domestication of the wolf began. Nevertheless, this process does appear to have been repeated several times, in several locations in Europe and Asia, over a period of many thousands of years, to the point where domestic dogs may already have been established in some parts of the world at the same time that wolves were being taken from the wild in others. Some of these attempts must have succeeded; others almost certainly failed, leaving no trace in today's dogs. The habit of burying dogs with humans seems, for some reason that is still unclear, to have been adopted only after domestication was well advanced; otherwise, there would be human graves from somewhere between twenty-five thousand and fifteen thousand years ago that contained the bones of proto-dogs, indistinguishable from those of wolves.

We can say for certain, however, that the earliest confirmed dogsâat fourteen thousand years agoâlogically represent not the beginning of

domestication but, rather, the end of its first phase, marking the point at which dogs became physically distinct from wolves. Before that, there must have been changes in the brains of wolves that made them suited to living with people but left little or no trace in their skulls for archaeologists to find today. The question still remains as to how long those changes took, how many of those first alliances between dogs and wolves failed, and how many wolves left their traces in the dogs of today.

Single footprints of a child and a canid in the Chauvet cave, in the Ardèche region of France

Since we can account for the diversity of dogs' DNA only by hypothesizing that individual domestications of wolves occurred in different parts of the world, these different “proto-dog” populations must initially have been isolated from one another, and probably remained so for thousands of years. As domestication progressed, however, these early dogs would eventually have become manageable enough to travel with people on large-scale migrations, thereby allowing individuals from one proto-dog population to meet up with, and begin interbreeding with, individuals from another. The resultant churning of the dog's gene pool probably started more than ten thousand years ago, such that even dog

remains old enough to be fossilized may have originated in wolf populations many hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

Thanks to this complicated timeline of domestication, the location of the original domestication events has proved impossible to pin down. The wolf itself is a highly mobile animal, even though it has not benefited from being transported around by man. Migrations of wolves, even since the dog was domesticated, have resulted in the incidence of almost identical DNA among individuals in regions as far apart as China and Saudi Arabia. Thus the DNA of modern wolves gives only very weak clues as to where domestication might have taken place.

Leaving the wolf to one side and approaching the locational problem from the opposite end, other biologists have recently analyzed the DNA of local “village dogs.” The scientists' hope was that these dogs would turn out to be the direct descendants of the first wolves to be domesticated in the area, and the assumption was that, as dogs dependent on humans, they were much less likely than wolves to have traveled long distances since then.

3

One recent study has suggested that, because the village dogs of southern China have the most varied DNA found so far, it was there that domestication must have occurredâbut subsequent research has revealed that village dogs are almost as diverse in Namibia, where the nearest wild wolf is three thousand miles away.

4

To have gotten that far, and to have become so widespread (there is little difference between the DNA of village dogs in Namibia and the DNA of those in Uganda), these dogs must have had considerable help from mankind; perhaps they accompanied humans on their various migrations around Africa. There also appears to have been a substantial amount of interbreeding between apparently localized village dog populations, resulting in a gradual trickling of greater diversity into their DNAâeven in places as isolated as Namibia.

Despite all this considerableâand continuingâresearch, there are still no firm answers to the question of where the dog was domesticated. It must have happened in areas where wolves occurred naturally, yet North America has been ruled out, since the DNA of North American wolves is quite different from that of domestic dogs. This leaves most of Europe and Asia as possible locations. Beyond this consensus,

there is a great deal of conjecture, even disagreement, among the various researchers pursuing a definitive answer.

5