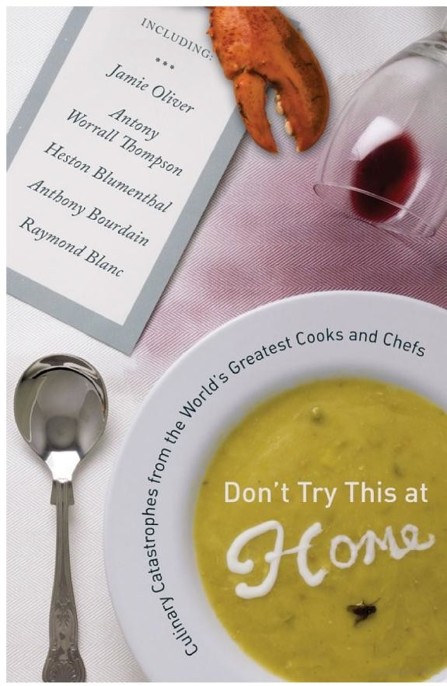

Don't Try This at Home

Read Don't Try This at Home Online

Authors: Kimberly Witherspoon,Andrew Friedman

Tags: #Cooking, #General

"Take a handful of culinary masters, toss in stories of utter humiliation or heartache, and you wind up with a spicy little

essay collection . . . Lots of fun for foodies both ardent and casual."

—

Kirkus Reviews

"A reminder that—in real life as in the kitchen—guts are as important as genius."

—

People

****

"A dishy collection of stories . . . lively additions to the

Kitchen

Confidential

genre."

—Julie Powell,

Food & Wine

"Surely, you think, real chefs aren't bedeviled by these problems. Think again. You can't even imagine the hidden kitchen

terrors recounted by professionals in

Don't Try This At Home"

—

Washington Post Book World

"Happily reminds us that even big shots have off days."

—

Publishers Weekly

"A sometimes comical and always unique glimpse behind the scenes of restaurant kitchens [and] a fantastic collection of personal

stories that depict these great chefs as real people."

—

Library Journal

"As in every other profession, chefs love their war stories. Finally someone had the good sense to collect some of the best."

—

Los Angeles Times

"Witherspoon and Friedman have gathered memorable stories from some of the best chefs in the world, and it's just plain satisfying

to read about their flubs."

—

New York Sun

"You'll love

Don't Try This at Home

. . . It's proof that celeb chefs climb into their checked trousers one leg at a time just like the rest of us."

—

Oregonian

"For those considering a life in the kitchen, these are cautionary tales, since they suggest that a career in a place replete

with sharp tools, open flames and stressed-out lunatics may be fraught with peril. But for true foodies, these comic tales

are a delight."

—

Winston Salem-Journal

"An inspiration for anyone who has been discouraged or shy to return to the kitchen after burning a soup or adding sugar instead

of salt to a recipe."

—

San Antonio Express-News

"What a wonderful idea for a bedside table book . . . these comic tales are a delight."

—

Virginian-Pilot

"There's often humor in disaster, especially at the hands and in the kitchens of some of the world's top chefs . . . You'll

smile and remember your own kitchen disasters."

—

Kansas City Star

A NOTE ON THE EDITORS

Kimberly Witherspoon

is a founding partner of Inkwell Management, a literary agency based in Manhattan. She is also the coeditor of the collection

How I Learned to Cook

and is very proud to represent seven of the chefs in this anthology: Anthony Bourdain, Tamasin Day-Lewis, Gabrielle Hamilton,

Fergus Henderson, Pino Luongo, Marcus Samuelsson, and Norman Van Aken. She and her family live in North Salem, New York.

Andrew Friedman

has coauthored more than fifteen cookbooks with some of the most successful chefs in the country, including Pino Luongo, Alfred

Portale, Jimmy Bradley, and former White House chef Walter Scheib. He is also the coauthor of

Breaking Back,

the autobiography of American tennis star James Blake. He lives in New York City with his family.

DON'T TRY

THIS AT HOME

Culinary Catastrophes from

the World's Greatest Chefs

Edited by Kimberly Witherspoon

and Andrew Friedman

BLOOMSBURY

To Summer and Paul

—K.W.

As always, to Caitlin, and for the first time,

to Declan and Taylor, two great kids

—A.F.

Copyright © 2005 by Inkwell Management

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Don't try this at home : culinary catastrophes from the world's greatest chefs / edited by Kimberly Witherspoon and Andrew

Friedman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-940-2

1. Cooks—Anecdotes. 2. Cookery—Anecdotes. I. Witherspoon, Kimberly. II. Friedman, Andrew, 1967-

TX649.A1D66 2005

641.5—dc22

2005017992

Excerpt from "Brick House": Words and music by Lionel Richie, Ronald LaPread, Walter Orange, Milan Williams, Thomas McClary,

and William King. © 1977 Jobete Music Co., Inc., Libren Music, Cambrae Music, Walter Orange Music, Old Fashion Publishing,

Macawrite Music, and Hanna Music. All rights controlled and administered by EMI April Music Inc. All rights reserved. International

copyright secured. Used by permission.

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury in 2005

This paperback edition published in 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

CONTENTS

MICHELLE BERNSTEIN

Two Great Tastes That Taste Great Together

HESTON BLUMENTHAL Lean Times at the Fat Duck

DANIEL BOULUD On the Road Again

ANTHONY BOURDAIN

New Year's Meltdown

SCOTT BRYAN

If You Can't Stand the Heat

TOM COLICCHIO

The Traveling Chef

SCOTT CONANT

This Whole Place Is Slithering

JONATHAN EISMANN

The Curious Case of

Tommy Flynn

GABRIELLE HAMILTON

The Blind Line Cook

PAUL KAHAN

(Not) Ready for My Close-Up

GIORGIO LOCATELLI

An Italian in Paris

MICHAEL LOMONACO

A Night at the Opera

PINO LUONGO

A User's Guide to Opening

MARY SUE MILLIKEN SUSAN FENIGER a Hamptons Restaurant &c Our Big Brake

SARA MOULTON A Chef in the Family

ERIC RIPERT

You Really Ought to Think

About Becoming a Waiter

ALAIN SAILHAC You're in the Army Now

MARCUS SAMUELSSON The Big Chill

LAURENT TOURONDEL Friends and Family

GEOFFREY ZAKARIAN The Michelin Man

N

EARLY TWO HUNDRED years ago, the legendary French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin observed that "the truly

dedicated chef or the true lover of food is a person who has learned to go beyond mere catastrophe and to salvage at least

one golden moment from every meal."

In these pages, a selection of the world's finest chefs share, in refreshingly frank detail, the stories of their biggest

mishaps, missteps, misfortunes, and misadventures. To our delight, much of what they salvage goes beyond the strictly culinary.

For their honesty, we thank the chefs themselves, who may surprise you as they discuss moments they'd rather forget, bringing

their stories to life with revelations of humility, self-doubt, and even shame. Disasters, especially those involving food,

are funny to look back on, but can be ego-deflating when they occur—it's a credit to these chefs that they are able to be

simultaneously profound and laugh-provoking.

As we consider the stories, a number of themes emerge: The fish-out-of-water syndrome that greets young cooks working and

traveling abroad proves itself a fertile breeding ground for near-farcical scenarios. The constant struggle to find and keep

good employees is another popular motif, leading to tales of everything from a blind line cook to a culinary faith healing.

Restaurants make for strange bedfellows, a truth examined in these pages via the tension between cooks and chefs and chefs

and owners. Finally, the chaos that ensues when a chef leaves his or her kitchen and takes the show on the road can lead to

countless unforeseen catastrophes.

For all of us, both cooks and noncooks, this book offers its own form of hope—evidence that even those who are the very best

in their chosen field, famous for exhibiting perfection on a nightly basis, can make a mistake, maybe even a disastrous one,

and then laugh at it, and at themselves.

Even more reassuring is how often, and how well, these storytellers improvise a way out, finding inspiration when they need

it most, and emerging victorious, even if it means sometimes telling a white lie.

"In my business, failure is not an option," writes one chef in his story. It's one thing to say that and quite another to

live it. These professionals live it on a daily basis, and we're grateful that they took time out to rummage through their

memories and pick out the worst—by which we mean the "best"—ones to share.

KIMBERLY WITHERSPOON

ANDREW FRIEDMAN

FERRÁN ADRIÀ

Ferrdn Adrià began his famed culinary career washing dishes at

a French restaurant in the town of Castelldefels, Spain. He has

since worked at various restaurants, served in the Spanish

military at the naval base of Cartagena, and in 1984, at the

age of twenty-two, he joined the kitchen staff of El Bulli. Only

eighteen months later, he became head chef of the

restaurant

—

which went on to receive its third Michelin star in 1997.

Adrià’s gift for combining unexpected contrasts of flavor,

temperature, and texture has won him global acclaim as

one of the most creative and inventive culinary geniuses in

the world;

Gourmet

magazine has hailed him as

S(

the Salvador

Dali of the kitchen.”

T

HE LOBSTERS ARE off," said the voice on the other JL end of the telephone.

This was

not

good news:

Off

is the word we in the culinary business use to express succinctly that something has spoiled, or gone bad in some way. Usually,

when something is off, it's so far gone that you can detect it by smell alone. Indeed, tasting something that's off is often

a very bad idea.

That the lobsters were off on this particular day was worse news than it would normally be. Normally, you could remove them

from your menu for one night, or secure enough replacement lobsters to remedy the situation before your first customers arrived,

and nobody would be the wiser.

But on the day in question, the lobsters were to be the main course of a private function we were catering: an international

medical congress in Gerona, a beautiful city in northern Catalonia, near the French border. Dinner was to consist of four

courses, what we called our Fall Menu: a chestnut cream and egg white starter, hot pickled monkfish with spring onions and

mushrooms, and a dessert of wild berries with vanilla cream. The piece de resistance was a lobster dish garnished with a cepes

carpaccio and a salad with Parmigiano and a pine nut vinaigrette.

And there was another detail that made the lobster news particularly alarming.

The dinner was to serve thirty-two hundred people.

When chefs have nightmares, it's moments such as these that play out in our heads. Unfortunately, I was wide awake and the

situation was very, very real.

A banquet for thirty-two hundred people was not something I did every day. Never in my twenty-five years as a chef had I catered

for anywhere close to such numbers. Our routine at El Bulli is fifty people a night. Admittedly, we serve fifteen hundred

dishes at each sitting, but still, going from fifty to thirty-two hundred is like jumping out of a warm, familiar bath into

an icy hurricane sea.

Naturally, our kitchen at El Bulli wasn't up to the task. So, to ensure ample space, we commandeered three production centers:

two vast kitchens nearby in Gerona and one in Barcelona. In addition, we hired plenty of extra help; more than a hundred people

were on the job. But even if we'd had a thousand people on board, that wouldn't have prevented the lobsters from going bad.

I received the lobster call at 8:00 a.m. on November 18, 1995—a date forever imprinted in my memory—and was instantly plunged

into a state of fear, uncertainty, and panic the likes of which I have never experienced in my professional life, and hope

never to experience again. The call came from the Barcelona kitchen, ironically situated in the city aquarium, right on the

waterfront.

It wasn't just some of the lobster that was off; practically our entire stock had fermented overnight: 80 percent of our lobster

haul was unusable, inedible, unfit for human consumption—never mind in any state to grace a dish prepared by the chefs of

what was then a two-star Michelin restaurant.

How could this have happened?

To maximize efficiency, we had shared out different tasks among the three production centers. The chief task of the aquarium

team was to clean, boil, and cut the lobster, before dispatching it to Gerona by road for assembly on the plate alongside

the carpaccio and the salad. They had already done the cleaning and boiling and cutting—three pieces of lobster per dish—the

night before, and the idea was that we'd simply load it all onto a van the next morning and off we'd go. Consequently, the

lobster, all cut up and ready, had been placed inside white polystyrene containers until morning. We'd never done such a thing

on such a scale and we supposed this was the right thing to do. The thermal containers insulated the lobster from the outside

temperature, which seemed like a perfectly good idea; indeed it

was

a good idea—at least for the hot road trip north to Gerona. When it came to the refrigerator, however, the night before, it

was an absolute calamity. Inside the containers, the lobster pieces were also insulated from the cold of the refrigerator.

And so, while we had carefully refrigerated the lobster, none of the cold could actually get through the polystyrene to reach

the lobster—which consequently remained at room temperature all night. Room temperature, for that length of time, was the

lobsters' ruin.

So, as you can see, it was the end of the world, the end of civilization as we know it. My first reaction—which I imagine

is the first reaction of anyone, in any context, on receiving catastrophic news—was, "It's not possible. I cannot believe

it. It cannot be true. Tell me, please tell me it's a bad joke." Once I had digested the indigestible and acknowledged that

it was, indeed, true, that I was awake and so it was actually a lot worse than a nightmare, I proceeded to descend into despair.

As second by mortifying second passed, the implications of what had happened sank in deeper: thirty-two hundred mouths to

feed in thirteen hours' time and the chief raw material of our main dish missing! I kept asking myself, "What are we going

to do? What the hell are we going to do? How in God's name are we going to manage now?"

But then, with my heart still hammering at a hundred kilometers an hour, I thought, Okay, calm down. This is probably an absolutely

hopeless case . . . but maybe there is something we can do, maybe we'll get lucky. Maybe there will be a miracle. So I started

to think and think, trying to come up with ways to get around this. Though the one thing I knew for sure was that, whatever

finally happened, ahead of me lay the most excruciatingly stressful day of my life.

The first and foremost question, of course, was how were we going to find the one thousand lobsters we needed—yes, a thousand—in

time to get them cleaned, cooked, delivered to Gerona (more than two hours away), and ready for consumption by nine o'clock

that same night. So, amid the utter chaos of it all, I gave the order, "Let's hunt down every last lobster in this city! Let's

get them all until not one is left!" We got on the phone and called everyone and anyone who could possibly have a stock of

fre sh lobster ready to go. "How many have you got? You've got fifteen? Great! Hold them, we'll go and collect them now .

. . How many have you got? Twenty-five! Fantastic! Can you bring them over? Perfect." After a frantic rush of phone calls,

we assembled a team of ten people in the aquarium kitchen—most of them having imagined that their work had been over the day

before—to clean, boil, and cut up the lobsters as they arrived.

By late morning, we realized that five hundred lobsters was the maximum that we were going to get. So what to do? Simple.

Here was the solution: reduce the contents of each dish by one piece of lobster, from three to two. That allowed us to stretch

the utility of the 20 percent that had not gone off overnight and to fill the quota we needed, especially as the happy news

filtered down from Gerona around lunchtime—this did help bring the temperature down a bit, at last—that a few hundred participants

of the medical congress would be going home early, and the total number of dishes required had fallen below the three thousand

mark.

By 11:00 a.m. we had our first batch ready, a hundred or so lobsters' worth. Off went the first vanload to Gerona. There was

some slight relief at its departure, but it was mostly overshadowed by the suspense, the worry that the van might break down

or crash or God knows what. In those days, we didn't have mobile phones. You couldn't keep track of the van's progress the

way you could now. So what happened was that the van driver, under strict orders to reassure us, would phone us at intervals—the

team in Barcelona

and

the two kitchens in Gerona—from a highway cafe or gas station to let us know that he was making progress, that he was edging

his way up to his destination. "It's okay. All's well. I'm on my way. Relax, guys!" We would all cheer with relief. But between

calls, it was hell. After what had happened, we were preconditioned for disaster. If anything could go wrong, we imagined,

it would.

And yet, miraculously, it didn't. Five vanloads of chopped lobster successfully made it from the Barcelona aquarium to Gerona—each

time inspiring the same drama of anxiety and reassuring phone calls—and finally, at about six in the evening, we looked at

the dish, reduced to two pieces of lobster but beefed up with an extra helping of cepes carpaccio, and knew that, barring

the habitual worries that always loom for a chef at this time of night, the immediate crisis was over. We had survived.

And, in the end, I learned some lessons from all this. First, never store things that need to be cold inside a fridge in closed

polystyrene containers. Second, keep a closer eye on things, especially when you have so much to do in so little time, when

your available reaction time, in case things go wrong, is drastically reduced. When you're feeding up to two hundred people

there's a certain amount of flexibility built in, some room to maneuver. More than two hundred and you're in a totally new

space. The logistical dimension of the exercise becomes so much more unwieldy.

The final and most valuable lesson I learned is that every day you start fresh. I know it sounds trite, maybe even foolish,

but it's true. Every day is a new challenge, a new adventure, and you must never be complacent; you must be constantly on

your toes, ready to deal with the unexpected, ready to respond—with as cool a head as you can—to whatever surprise comes.

(Translated from the Spanish and

co-written with John Carlin)