Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? (44 page)

Read Dorothy Parker: What Fresh Hell Is This? Online

Authors: Marion Meade

Tags: #American - 20th century - Biography, #Women, #Biography, #Historical, #Authors, #Fiction, #Women and literature, #Literary Criticism, #Parker, #Literary, #Women authors, #Dorothy, #History, #United States, #Women and literature - United States - History - 20th century, #Biography & Autobiography, #American, #20th Century, #General

24) Dorothy seated between Laura Perelman and her sister Helen in Hollywood., 1943. Dorothy proudly cunducted Helen on a tour of the movie capital and introduced her to stars such as Marlene Dietrich. “Everyone makes a swell fuss over Dot,” Helen wrote to her son. (HELEN IVESON, ROBERT IVESON, MARGARET DROSTE, SUSAN COTTON)

25) Dorothy and Alan’s second wedding, August 17, 1950, in Hollywood. Dorothy explained the remarriage by telling wedding guests, “What are you going to do when you love the son of a bitch?” The marriage, however, failed to last even a year. (WIDE WORLD PHOTOS)

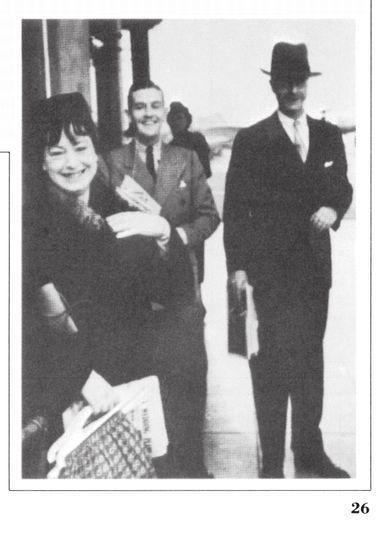

26) Dorothy and Alan with Donald Ogden Stewart at Los Angeles Airport in the late 1930s, before embarking on one of their frequent cross-country air trips between Hollywood and their farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Dorothy is carrying her ever-present knitting bag. (DONALD OGDEN STEWART, JR.)

27) Alan and Dorothy reunited after an eleven-year separation, outside Alan’s bungalow in Norma Place, Hollywood, 1962. He is behind the wheel of his new green Jaguar, confidently purchased in the hope that a script slated for Marilyn Monroe would lead to a rebirth of their career as a screen-writing team. (PAUL MILLARD)

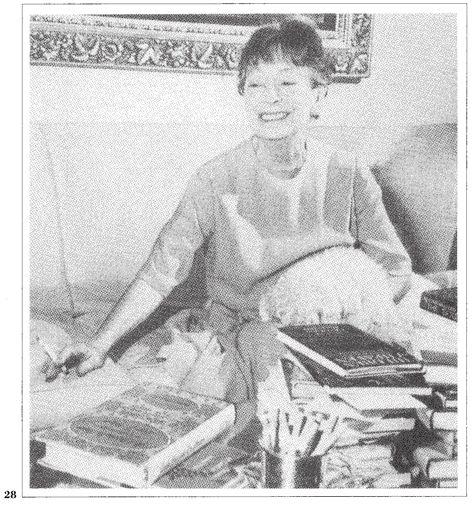

28) A grinning Dorothy, holding her poodle Cliché, after deciding to remain with Alan in Hollywood, June 1962. On the table are heaped review copics that she received for her monthly book column in

Esquire,

a task that became increasingly difficult to carry out. Unemployment insurance—and the sale of review copies—helped support them during lean times. (© 1962 LOS ANGELES TIMES)

That summer Alan was offered a job playing juveniles with the Elitch Gardens stock company in Denver, which meant a separation of several months. Dorothy decided to go along with him; they could rent an apartment together, and she could write while he was busy at the theater. Alan insisted that it would be a wise move to buy a secondhand car and motor across the country. He promised the trip would take only four days, and Dorothy began to dream of their romantic progress toward the western sun, riding through fields of windswept grain. Among those who saw them off on the morning of June 8 was Marc Connelly, who recalled that their car, a 1929 Ford that resembled a sitz bath, “was the most goddamnedest most-loaded vehicle you ever saw. There was more junk in it, completely unnecessary stuff,” not to mention the two Bedlingtons. When they reached Newcastle, Pennsylvania, Dorothy stopped to telegraph the Murphys, who were sailing for Europe the next day.

THIS IS TO REPORT ARRIVAL IN NEWCASTLE OF FIRST BEDLINGTON TERRIERS TO CROSS CONTINENT IN OPEN FORD. MANY NATIVES NOTE RESEMBLANCE TO SHEEP. COULDN’T SAY GOODBYE AND CAN’T NOW

BUT GOOD LUCK DARLING MURPHYS AND PLEASE HURRY BACK. WITH ALL LOVE, DOROTHY.

The trip west delighted Dorothy. She decided that the finest people who existed operated filling stations and that most Americans west of Pennsylvania lived entirely on catsup. Wolf sat on her lap the whole trip; Cora annoyed Alan. On the fourth day, having just crossed the Nebraska-Colorado state line, they decided it would be fun to wire Don Stewart in Hollywood:

WE ARE IN JULESBURG, COLORADO, IN OPEN 1929 FLIVVER WITH TWO BEDLINGTON TERRIERS. PLEASE ADVISE.

Stewart had no suggestions and replied,

I HAVE NEVER BEEN IN JULESBURG, COLORADO.

Arriving at Elitch Gardens, they stepped into more “fresh hell.” The telegram to Stewart had been signed with both their names and apparently he showed it to a Hollywood journalist. “We got out of the car into a swirl of reporters, camera men, sports writers, and members of the printers’ union,” Dorothy recalled. They naively assumed they would be able to live together as in New York but immediately realized their mistake. “Eyebrows,” Connelly said, “shot up to the tops of the cathedrals. I don’t know why they expected to go out to Denver and get away with having an affair.” When they heard phrases like “living in sin,” they both lost their heads. Before Dorothy could stop him, Alan’s southern chivalry had bounded to the forefront, and he boldly declared that they were married, lies that led to further lies because naturally the reporters then wanted details about where and when. Improvising, Alan said the wedding had taken place last October by a justice of the peace in Westbury, Long Island. Dorothy told other reporters that the ceremony had been performed at her sister’s house in Garden City. When the wire services searched the vital statistics of North Hempstead Township, they could find no registry of the marriage, nor had the municipal clerk issued a marriage license. When they called Helen’s home, Victor Grimwood said it was news to him, in fact he was quite sure no ceremony had been performed at his house.

There seemed to be only one way to save face. A few days later, on the evening of June 18, they drove across the state line to Raton, New Mexico. It was nearly midnight by the time they located a justice of the peace. In an effort to conceal the marriage, Dorothy gave her name as Dorothy Rothschild, age forty, and Alan said he was Allen [sic] Campbell, age thirty-two (he was only thirty). The next day, back in Denver, Dorothy sent her sister a wire from one of the dogs:

COMMUNICATION HAS BEEN IMPOSSIBLE IN APPALLING CONFUSION. BUT MANAGED UNANNOUNCED DRIVE TO NEW MEXICO YESTERDAY WHERE PARENTS DIFFICULTIES PRIVATELY SETTLED, IT IS HOPED

FOR ALL TIME. BOTH VERY HAPPY. BEST LOVE AND MOTHER IS WRITING.

She signed the telegram CORA. A wire-service photograph snapped the day before their marriage reveals that they were in fact very happy. Dorothy, trim, radiant, and looking closer to thirty than forty, wore a dress printed all over with daisies and seemed like an adorable Japanese doll next to Alan, who was beaming as usual.

Still, reporters continued to trail them. Dorothy began to feel persecuted. “Oh, this is the first real happiness I’ve had in my whole life,” she cried. “Why can’t they let us alone?” Her attorney, Morris Ernst, advised showing the marriage certificate but keeping well concealed the date or place it was issued, which she did. While she was at it, she threatened to bring a fifty-thousand-dollar libel suit against the New York Post for suggesting she had lied about having been married the previous autumn.

Otherwise she was, as she wrote in an ebullient letter to Aleck Woollcott, “in a sort of coma of happiness.” Being Alan’s wife was “lovelier than I ever knew anything could be.” She also felt rapturous about her new status as a wife. When she heard from Scott Fitzgerald in early July, she wired him back:

DEAR SCOTT THEY JUST FORWARDED YOUR WIRE BUT LOOK WHERE

I AM AND ALL MARRIED TO ALAN CAMPBELL AND EVERYTHING ALAN PLAYING STOCK HERE FOR SUMMER.

She sent him deepest love from both of them.

It was one of the happiest summers of her life. For only fifty-five dollars a month they leased a furnished bungalow at 3783 Meade Street, which Dorothy named “Repent-at-Leisure.” For the first week or so, they attempted to keep house for themselves. Alan did the cooking and put tomatoes in every dish he prepared, while Dorothy’s contribution to housekeeping was a botched effort to make the bed. She offered to help in the kitchen but failed sublimely. Alan ordered her to stay out. Once rehearsals started, the system broke down, and they had to seek help from an employment agency. They needed, Alan stated, a man who would market, cook, serve, clean, and keep the cigarette boxes filled. A man was preferred because, in their experience, maids tended to chatter, and it was essential for any servant of theirs to observe silence. His wife, he explained to the agency, must never be disturbed: She wrote.

During the first week, the newlyweds hired and fired three servants, one of whom turned out to be a nonstop talker. Dorothy disliked him so passionately that she was inspired to write a short story about him, “Mrs. Hofstadter on Josephine Street,” which was probably the quickest story she had ever written. It appeared in the August 4 issue of

The New Yorker.

They finally retained a housekeeper, who insisted on calling Dorothy “honey” and who was genteelly fond of her liquor.

As for Dorothy, she was drinking less. Blaming the altitude, she explained that “two cocktails and you spin on your ass,” but she also felt happy and relaxed. Expecting to hate Denver, she confessed that “I love it. I love it. I love being a juvenile’s bride and living in a bungalow and pinching dead leaves off the rose bushes. I will be God damned.” Ensconced in the little bungalow, she did nothing but eat, sleep, and knit socks for Alan. Some days she saw little of him because he was in rehearsal, then performed at night, including Sunday. Dorothy was fanatical about staying away from Elitch Gardens; she had once read in a movie magazine that Hollywood respected Clark Gable’s wife for staying out of her husband’s business. Probably this was a wise decision on Dorothy’s part because she had taken to making wildly slanderous observations about the company’s leading lady, telling Alan that she looked like “a two-dollar whore who once commanded five.”

Some of Dorothy’s closest friends did not take her marriage seriously. Aleck Woollcott, told of her happiness, only snorted sourly and replied, he had read nothing of hers lately that was worthwhile, “That bird only sings when she’s unhappy.” Eventually he became close to Alan. They shared many of the same obsessions and sensibilities and, to a lesser degree, they had in common confusions about gender identity. Dorothy knew that Woollcott accepted her marriage when he began playing his usual practical jokes. After Alan applied for a department store charge account and gave Woollcott as a financial reference, Aleck responded with a fake carbon copy of his reply to the store:

Gentlemen:

Mr. Alan Campbell, the present husband of Dorothy Parker, has given my name as a reference in an attempt to open an account at your store. I hope that you will extend this credit to him. Surely Dorothy Parker’s position in American letters is such as to make shameful the petty refusals which she and Alan have encountered at many hotels, restaurants, and department stores. What if you never get paid. Why shouldn’t you stand your share of the expense?