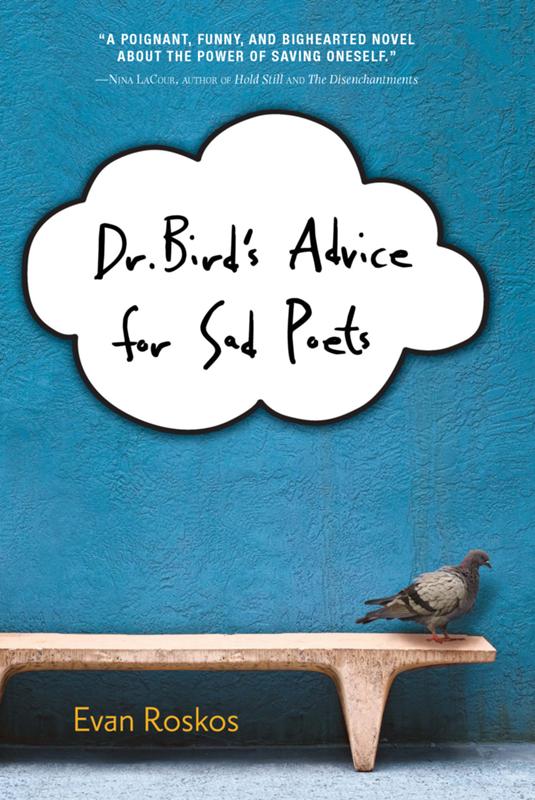

Dr. Bird's Advice for Sad Poets

Read Dr. Bird's Advice for Sad Poets Online

Authors: Evan Roskos

Copyright © 2013 by Evan Roskos

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Houghton Mifflin is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Roskos, Evan.

Dr. Bird’s advice for sad poets / Evan Roskos.

pages cm

Summary: A sixteen-year-old boy wrestling with depression and anxiety tries to cope by writing poems, reciting Walt Whitman, hugging trees, and figuring out why his sister has been kicked out of the house.

ISBN 978-0-547-92853-1

[1. Depression, Mental—Fiction. 2. Family problems—Fiction. 3. Poetry—Fiction.] I. Title. II. Title: Doctor Bird’s advice for sad poets.

PZ7.R71953Dr 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012033315

eISBN 978-0-544-03565-2

v1.0313

To Rin

and

Laura

And henceforth I will go celebrate any thing I see or am,

And sing and laugh and deny nothing.

1.—Walt Whitman

I YAWP MOST MORNINGS

to irritate my father, the Brute.

“Yawp! Yawp!” It moves him out of the bathroom faster.

He responds with the gruff “All right.” He dislikes things that seem like fun.

I do not yawp like Walt Whitman for fun. Ever since the Brute literally threw my older sister, Jorie, out of the house, I yawp at him because he hates it. My father says reciting Walt Whitman is impractical, irrational. My father says even reading Walt Whitman is a waste of time, despite the fact that we share his last name. My father says Walt Whitman never made a dime, which is not true. I looked it up. Not on Wikipedia but in a book that also said Walt used to write reviews for

Leaves of Grass

—his own book!—under fake names.

Who does that? Walt does!

The perfect poet for me. I’m a depressed, anxious kid.

I hate myself but I love Walt Whitman, the kook. I need to be more positive, so I wake myself up every morning with a song of my self.

Walt says:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I say:

I am James Whitman.

I define myself and answer the question that was asked with my momentous birth!

I am light! I am truth! I am might! I am youth!

I assume myself and become what you assume!

I leap from my bed, bedraggled but lively! Vigorous, not slowpoked and sapped with misery (despite my eyes and aching teeth, which grind all night)!

I bathe, washing the atoms that belong to me but are not me.

I brush my teeth. Away! Away! Gummy grime of six hours’ sleep! Six hours of troubled dreams will not slow my hands as they scrunch my cowlicked hair into an acceptable—no,

vital

—posture!

I adorn a bright shirt—sunburst of red on white, a meaningless pattern. But so is a sunset! So are clouds! I choose low-cut socks and cargo shorts with enough pockets to carry all my secrets.

It is April, the first warm day of the year, a day where I can loaf and lounge and contemplate a spear of grass lying in my palm. A day when the sun has to work hard to burn off the mildew of a dillydallying winter that beat me to a pulp. A day when I forget depression, forget my beaten and banished sister, Jorie, living alone somewhere. A day to

YAWP!

out across the moist air of the park on my way to school. I do not mind the grass tickling my ankles. I do not mind the chill because I have my old green hoodie infused with the musk of the prior fall, the dander in the hood, the history of sweat!

Ah, my self!

I sing through the park, greeting trees, stopping beneath them to stare at the way the morning sky filters through the newborn leaves.

I chitter at squirrels, who celebrate themselves.

“Hello, my nutty friends!”

Contemplating my demeanor, they hold their tiny paws to their mouths. But I need to keep walking, to keep moving, to get to school before my mood falls apart.

Walt says:

Dazzling and tremendous how quick the sun-rise would kill me,

If I could not now and always send sun-rise out of me.

Some days I feel like I’m on the verge of supernova-ing.

Other days I’m a leaf of grass.

Every day I miss my sister, expelled from home and school with just a few months left. No prom, no graduation, no celebration, no gifts. A metaphorical footprint on her ass after years of literal bruises on her body put there by my mother, the Banshee, and my father, the Brute. I loafed in my room while she raged on the front lawn, cursing the very house for the miserable nails that held it together to protect me and my mother and yawp-hating father.

I hug trees, dozens on especially bad mornings when the walk to Charles Cheeseman High School feels long and insufferable.

When I hug trees, the bark marks my cheek and reminds me I’m alive. Or that my nervous system is still intact. The trees breathe all the time and no one really notices. They take in the air we choke on. They live and die in silence. So I hug them. Someone should.

When people see me hugging an old maple tree in the park, they probably think I’m a kook. I am okay with that, though I’d prefer they not let me know what they think of me. Let me be, I ask.

Like Walt says:

I cannot say to any person what I hear . . . . I cannot say it to myself . . . . it is very wonderful.

I also hug trees to apologize to them. When I was in fourth grade, Jorie and I threw chunks of scrap bricks at a dogwood tree. Brick can really do some damage. Tears the thick skin right off and exposes pale tree flesh. When we stopped for a moment to collect the larger brick bits, my sister looked real close at what we did and said she felt horrible.

“The tree is crying!” she said.

“A tree’s a tree,” I said, ready to adjust my technique for some real damage. “It can’t feel anything.”

But Jorie said that just because the tree couldn’t feel or speak or think didn’t mean we should throw bricks at it. She left me in the backyard. I spent an hour trying to put bark back on the vulnerable tree.

ANOTHER TERRIBLE HIGH SCHOOL DAY

awaits, though I’m calm after embracing four trees that will outlive me. As I step out of the park onto the pale sidewalk, I see Beth King across the street. The sight of her reminds me what a girl in a spring-friendly outfit looks like:

wonderful.

(Imagine butterflies so drawn in by a bright flower that they forget how to fly; that’s the feeling I get from Beth in her warm-weather outfit.)

I pause to hug one last tree before jaywalking. I want Beth to notice me but not the crazy part of me. So, I keep my hand on the tree trunk and let her move ahead so I can follow her.

As we walk, I see a bird in the street. It’s not flying away, and I know birds tend to hop a lot when scrounging for food. This one flaps one little wing like it’s injured. I look at the bird and at Beth and back at the bird. For a moment I think it would be awesome if she noticed the bird and showed some kind of concern, but she’s texting on her phone very intently.

A car passes and I cringe—but it misses the bird, who flaps its wing frantically. I need to save the bird! No one else notices these things!

If I can grab the sparrow (or finch or swallow) and get it to the other side of the street, then Beth will see I’m a sensitive, bird-loving man! Huzzah! A heroic grab of the bird and a well-timed “Yawp!” will win her heart!

I jog at the perfect angle so that I can grab the bird, dodge oncoming traffic, and arrive light-footed on the opposite curb. Maybe even a somersault! This will be the greatest how-we-met story ever!

I dart into the street and make a quick grab for the critter. I need to hurry to get through the lane and over to the other sidewalk, so Beth can cheer me and hug me and appreciate the acrobatic Olympic double-roll hop I’ve just somehow initiated.

I’m airborne!

I’m really a superhero!

I think I’ve been hit by a bus!

The horizon flips around—twice, I think. The bird crumples in my hand. Suddenly I cannot see clearly. I hold on to the bird but lots of things hurt.

The diesel smell of the bus is the smell of my shame. The kids on the bus are laughing at me. I know none of them thinks this is a serious issue. The bus driver comes out and screeches at me.

“What the heck are you doing?! Running out in front of me? How’d you miss a big yellow bus?”

I hold up the bird.

“I was saving a bird.”

The bird’s not struggling to flee my grip. The bird might be dead!

“That’s a damn Tastykake wrapper, you idiot!”

So it is.

I look over and Beth is gone. She didn’t see me almost die. Or she did and didn’t think it was that important.

EVERYONE AT SCHOOL

is calling me Short Bus.

A kid in the hall says, “High-five, Short Bus!”

I hold up my cast and the kid tries to bump our forearms in mock camaraderie.

At least I’m famous, right? (How many people in history have thought “At least I’m famous!” for doing something stupid? Probably tons, thanks to YouTube.)

Before homeroom, my friend Derek tries to make me feel better with the only wit he can muster.

“Heard you tried to jump on the short bus to be with your own kind.”

I should mention he’s my only real friend.

Derek and I have known each other since preschool. He’s a year ahead of me, though he still lowers himself to be seen with a high school junior now known as Short Bus. Derek tends to get along with tons of people, which I admire but also find curious. I’m not sure how he gets people to like him. People just do.

Sometimes I think that people automatically like Derek because his dad died. That seems mean, but there it is. It’s not just that with Derek, though; he listens and laughs and never says bad stuff about anyone behind their back. Derek’s dad died when Derek was in fifth grade. It was my first funeral. Derek’s relatives swarmed his mother and sisters, but kept telling him he was the man of the house in a way that seemed very official and menacing. Derek told me a few days after the funeral that he didn’t know what being a man of a house meant. We speculated that he now had to sleep in his parents’ bed and go to his dad’s job.

Derek has a permanent marker ready to sign my blank cast. (My mom offered to sign it, but that’s the kind of hit to my already terrible reputation I wouldn’t survive.) I don’t watch what he’s writing because his proximity to me is unnerving. When people get this close to me—doctors, teachers, waiters—it puts me on edge. Derek doesn’t seem to care how close his body is to anyone in the world. In fact, it’s like he’s allergic to clothes. He plays basketball shirtless. He mows the lawn shirtless. He even grills shirtless. He sits around his house in nothing but boxers, even when his mom and sisters are around. He’s usually one awkward movement away from flashing his ball sack.