Drama (12 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

I had never seen my father like this. Witnessing his tantrum, I was frozen in my seat, caught between anxiety and relief. I hated to see Devereaux treated so ruthlessly, but I was enormously relieved to see him finally getting the thrashing he needed. His passion spent, Dad instructed Romeo and Juliet to begin the scene again from the top and then strode back to his seat. Devereaux had been shaken to the core, but he climbed to his feet, shook his head and his hands, and began again. The second time through, the scene was transformed. Devereaux never grew into a great Romeo, and the entire play never quite caught fire. But my father’s harsh medicine had been both necessary and effective. From that moment on, Devereaux, Romeo, and the production itself were all mightily improved.

That day I felt that I had seen my father at his very best. His love of Shakespeare and his passion for theater were abundantly on display. He filled me with admiration and pride. Questions hung in the air, of course. Why did he wait until dress rehearsal to tear apart an actor’s performance? Why did he allow Romeo to wear that awful costume, makeup, and hairdo? Why was such a fatuous actor ever cast in the first place? Besides compromising the production, wasn’t this a cruel disservice to the actor himself? Such questions went to the very heart of my father’s strengths as a theater manager. But as I sat watching him in that darkened auditorium, either those questions didn’t occur to me or I scrupulously ignored them. And why should I have cared, anyway? What emotional investment did I have? After all, this was not my career. I wasn’t going to be an actor. This was a lark, a fun summer before I went off to college. It was years before I asked all those questions about my father. When I finally did, the answers would weigh heavily on me.

Veritas

T

he dreams of an artist die hard. Despite all the fun of my first season with the Great Lakes Shakespeare Festival, I was still nursing ambitions of being a painter. And so it was that, halfway through my freshman year at college, I set my sights on Skowhegan, Maine, for the upcoming summer. As it is today, Skowhegan was the site of a summer-long art school and the seasonal retreat for a whole colony of high-powered New York painters. In my dorm room I filled out an application, typed out a brief essay, assembled slides of drawings and paintings from my Art Students League days, and sent off the whole package. I was bursting with high hopes and creative zeal. What with the hectic frenzy of the summer festival and the crushing workload of my freshman year, my artistic output had slowed to a trickle. I was counting on a meditative summer in Maine to get it going again. In the weeks after I mailed my application, I awaited word.

While I waited, I went home to my family in Princeton for Spring Break. On my first day back, my father had a bright idea. Since arriving at McCarter Theatre, he had made the acquaintance of Ben Shahn, an authentic American master of painting and printmaking whose home and studio were in nearby Roosevelt, New Jersey. For years Shahn had been a summertime fixture at Skowhegan and a dominating presence at the art school there. To boost my chances of admission, Dad called up Shahn himself and asked if I could visit his studio to talk to him about the summer program. Shahn said yes, and a few days later Dad and I drove out to Roosevelt to meet with him.

When we walked into his bright, airy studio, the bespectacled Shahn was working on a series of small watercolors. He was enthroned like a pasha, surrounded by a happy clutter of drawings, paintings, photos, and art supplies. Afternoon sun poured in the windows, filtered through the spring leaves of birch trees out in his yard. Mozart played softly on the radio. I took in the scene with awe and envy. It was everything I had dreamed of: a serene creative idyll, perfectly conducive to the unfettered flow of art.

But Ben Shahn himself was anything but serene. In his late sixties, he had the big head, broad shoulders, meaty hands, and expansive girth of a longshoreman. He spoke in a deep growl and his manner was brusque. His defiant, left-leaning politics, frequently expressed in his social realist paintings, seemed to color his every word and gesture. He needled and challenged me, rabbinically testing my fiber with irascible good humor. The questions came thick and fast. What have you done? Where have you studied? Whose work do you like? Why do you want this? What do you aspire to? Where do you stand? I burbled my earnest answers, feeling utterly intimidated and inadequate. Then came the biggest question of all:

“If you want to be an artist,” he barked, “what the hell are you doing at

Harvard

?”

I

went to Harvard because I got in. This is not the best reason to pick a college, but in retrospect, it’s the best reason I can come up with. In those days, to an even greater extent than today, the very word “Harvard” represented the pinnacle of high school achievement, the ultimate flatterer of a seventeen-year-old’s vanity. The heady aura of the place swept aside all other considerations. This was still the era of Jack Kennedy’s pre-Dallas Camelot, and the place shimmered with his reflected glory. Admittance to Harvard was a gilded invitation to join the company of the best and the brightest, long before that phrase had taken on its dark, ironic overtones. If you got in, you went, simple as that. My letter of admission arrived, I accepted without hesitation, and the following September I arrived in Cambridge and moved into Wigglesworth Hall, my freshman dorm, in the shadow of Widener Library. I was a newly minted Harvard undergraduate, Class of 1967, without knowing a thing about the place and, in fact, without ever having laid eyes on it.

From the moment I arrived at Harvard, I sensed something in the air. It emanated from the moist red bricks of Sever Hall. You heard it in the Brahmin drawls of the all-male undergrads. You saw it in the lazy waggle of their cigarettes and the droopy forelocks of their unbarbered hair. You could practically smell it on their damp tweed sport coats and crimson wool scarves. It was a certain indefinable culture of languid male success, an unspoken awareness that having gained access, you were expected to effortlessly excel, both at Harvard and beyond. Everyone there bore these great expectations in one of two ways: they either regarded them as a mantle of privilege or as an onerous burden. This made the Harvard men of those days highly susceptible to virulent strains of self-importance, self-doubt, self-contempt, or some complex combination of all three. However you responded to the pressures of the place, one thing was clear: to thrive at Harvard, or even to survive there, you must stake out some domain where you can

succeed

, and move into it like an invading army.

It didn’t take me long to find mine.

By centuries-old tradition, Harvard turned up its nose to formal training in the arts, an attitude that is only just giving way in this day and age. And yet its student body at any given moment has always been packed with students of exceptional talent, ready to pour their energies into extracurricular artistic activity. How else can you explain the long list of career artists that Harvard has produced over the years: Robert Frost, Leonard Bernstein, Alan Jay Lerner, Arthur Kopit, Jack Lemmon, Pete Seeger, and John Updike from earlier generations; and more recently Yo-Yo Ma, Terrence Malick, Christopher Durang, Bonnie Raitt, John Adams, Peter Sellars, pianist Ursula Oppens, sax player Josh Redman, and movie stars Natalie Portman and Matt Damon. All of these notables were feverishly active in the arts at Harvard. Only one or two of them actually studied their discipline there.

Read over that list again. You will notice a glaring omission. Not one of these impressive artists worked in the visual arts. Ben Shahn was right. You didn’t go to Harvard to paint pictures. The year before I’d arrived, Harvard had unveiled the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, a stunning piece of sweeping architecture designed by Le Corbusier. A seductive photo of the building had caught my eye the year before, when I was sifting through college literature and choosing schools. On one of my first days on campus I went inside it and snooped around its glass, steel, and concrete interior. The bright rooms were weirdly empty. The walls were covered with what looked like technical drawings, analytical design projects featuring black-ink outlines of geometrical shapes, seemingly intended to transmute fleshly art into bloodless science. By all evidence, art at the Carpenter Center had to meet some dry, academic, almost technological standard or it was disallowed. There were no paint-smeared rags, no turpentine smell, no racks of unfinished canvases, no plaster dust, no clutter, no mess. It had the feel of an art school where actual artists had been told that they need not apply. Clearly this was not the place for me. I walked out the gleaming glass doors and for the next four years I barely went back.

That same day, I sought out another building. This one lay blocks away from Harvard Yard, crouching on Brattle Street like a mutinous exile. This was the Loeb Drama Center, a state-of-the-art two-theater playhouse entirely devoted to extracurricular dramatics. The building was only two years old but already looked comfortably lived in. The walls were lined with photos of student productions. The bulletin boards were crammed with casting calls and handbills. Coats and book bags were flung in every corner. Laughter and fast talk echoed in the halls and spilled out of the open doors of rehearsal rooms. And lolling everywhere, with an air of cocky ownership, there were students. These students, the denizens of “the Loeb,” were funky artistic types of both sexes, and included the first Harvard upperclassmen and graduate students I had ever laid eyes on. They were a breed apart from the timorous, tentative young men in jackets and ties who huddled together at meals in the Freshman Union. Taking it all in, my heart raced and creative juices pumped through my veins. I could hardly believe my good luck. In my very first week, I had found my place at Harvard.

In the meantime, I had also found a friend. He was hard to miss. He was my roommate. Weighing our histories, Harvard had housed me in Wigglesworth Hall with two other freshmen with an artistic bent. One of them was David Ansen. David and I could hardly have been more different. He hailed from Beverly Hills High School, a child of Hollywood whose father had written short films and trailers in the movie industry. In those days, David was an aspiring writer of fiction, poetry, and plays. His serious demeanor and bookishness were belied by a worldliness, sly humor, and vivid sexual history. We probably found each other equally exotic. When he walked into our dorm room for the first time, I was already there. I had staked out a corner desk and was laboring away at a woodcut, barely acknowledging his arrival. A woodcut! An hour after arriving at Harvard! Who

was

that strange boy? David later told me that, at first sight, he had thought I was a painfully shy hayseed from the South, invited to Harvard as part of an outreach program, there to practice and refine some kind of arcane hillbilly handicrafts. From such unpromising beginnings we soon became best friends, and we’ve been best friends ever since.

With his Hollywood pedigree, there was absolutely nothing that David did not know about film. Within days of that first meeting, we went to a movie. It was the first of scores of films that we saw together over the next four years. He became my de facto professor of the history of film, eager to drag me to both new movies and old ones that he’d seen several times before. And what a time for an intensive movie tutorial! This was the early sixties, and our generation was drunk on cinema. Boston was dotted with revival houses, presenting an unending repertory of classic films from every era and every genre. New international movie trends kept crashing on our shores like waves. In France there was the Nouvelle Vague, in Sweden there was Ingmar Bergman, in Italy there were Fellini, De Sica, Visconti, and Antonioni. As for American filmmakers, they were on the verge of their greatest period of innovation, with Stanley Kubrick in the vanguard. Ansen was there to mark every development, trace its roots, and tell me all about it.

But David was no cinema snob. His interests extended far beyond art films. He was just as eager to see

Goldfinger

,

Lawrence of Arabia

,

A Hard Day’s Night

, or, for the umpteenth time,

Casablanca.

And whenever he got home from a movie, he would take out a little notebook and add the title to a master list he kept of every film he had ever seen. In the same book, he wrote down his personal picks every year for Oscar winners in every major category, along with his predictions for what the actual winners would probably be. It is amazing that, given David’s obsession with movies, it never occurred to any of us (himself included) that he would end up a film critic. But of course that is exactly what he became. For over thirty years he was the lead critic for

Newsweek.

I never thought I’d be a movie actor, either, but in the course of those three decades, David Ansen, with studied neutrality, reviewed my performances on film ten different times.

Utopia

W

ithin weeks of my arrival in Cambridge, the floodgates had opened and I was swept into the world of Harvard undergraduate drama. Days after that first visit to the Loeb, I auditioned for the first big Main Stage show of the year and landed a major role in it. I was to be Reverend Anthony Anderson, one of the two rival leading men in Shaw’s

The Devil’s Disciple

(my father had played Dick Dudgeon, the other leading man, back in Oak Bluffs when I was five years old). I was the only freshman in the show, and as I rehearsed with the rest of the cast in the basement of the Loeb, I keenly felt my rookie status. I was an unlicked whelp among a lot of swaggering juniors and seniors, the youngest actor playing the oldest of the major roles. But my years of experience fortified me. In rehearsals I held my own, and in performance I was self-assured and commanding. The joke went around that in three more years I’d be running the place.

As it happened, my Harvard years were the most active and creative of my life. The fact that there was no academic program in theater meant that all of us operated in an atmosphere of reckless, unsupervised creative abandon. It was the last time I worked in the theater for the pure, unfettered joy of it. Some of the work was excellent, much of it was dreadful, but its quality was never really the point. Joy was the point. If someone wanted to try something, there was somewhere to do it, a starvation-level budget to pay for it, and an entire army of eager classmates ready to join in. These were smart young kids, brilliant students of science, math, economics, political science, you name it. Only a tiny fraction of them ever dreamed of actually pursuing a life in the creative arts. They were merely looking for an outlet, a social context, and a little fun outside the demands of a Harvard undergraduate education. And yet hundreds of them spent more than half their waking hours feverishly slaving away—as stagehands, set builders, costumers, lighting technicians, musicians, designers, producers, directors, and, yes, actors—on one of the fifty-odd shows which, at any given moment, were in various stages of production on that vast, sprawling campus.

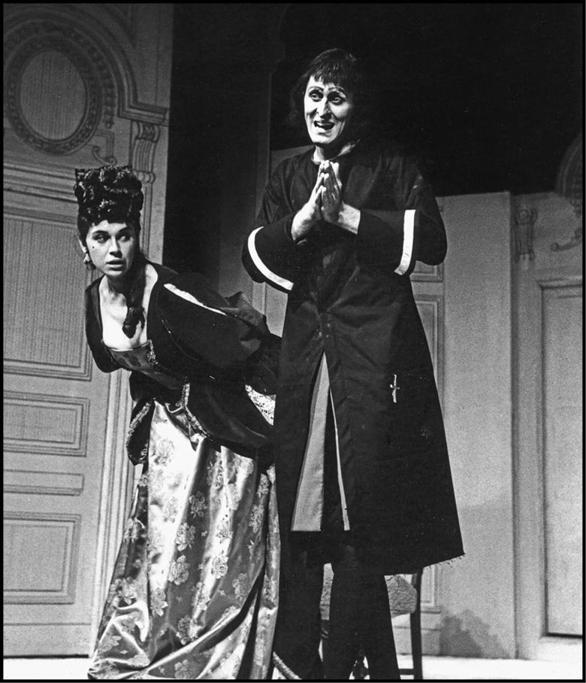

Courtesy Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

To illustrate the variety and creative ferment of those Harvard years, here, in a rough chronology, is a sampling of my extracurricular entanglements there:

• I played the title roles in

Tartuffe

,

Macbeth

, Christopher Marlowe’s

Edward II

, and Lord Byron’s

Manfred

(I bet you’ve never seen

that

one onstage).

• I played the ancient, blinded Duke of Gloucester in

King Lear

(I was eighteen at the time and wore a wig once worn by Sir John Gielgud).

• I directed and acted in a one-act play by Molière called

The Forced Marriage

(I also designed the set and created masks for all the characters).

• As president of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society, I directed and played the Learned Judge and the Lord Chancellor in

Trial by Jury

and

Iolanthe

, respectively.

• I recruited dancers from the Boston Conservatory and staged a double-bill of one-act opera-ballets made up of Stravinsky’s

Renard

and Menotti’s

The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore

(I made the masks for that one, too).

• I directed, designed, and played the role of the Devil in a fully staged version of Stravinsky’s

L’Histoire du Soldat

.

• In a Radcliffe College common room, I recited Dylan Thomas’s poetic reminiscence “A Child’s Christmas in Wales.” Beside me, a Radcliffe girl in a black leotard (future actress Lindsay Crouse) did a Jules Feifferesque dance interpretation of the entire piece.

• With a few ringers from the New England Conservatory of Music, I staged Mozart’s

Le Nozze di Figaro

in a dorm dining hall (the conductor grew up to be the Pulitzer Prize–winning composer John Adams).

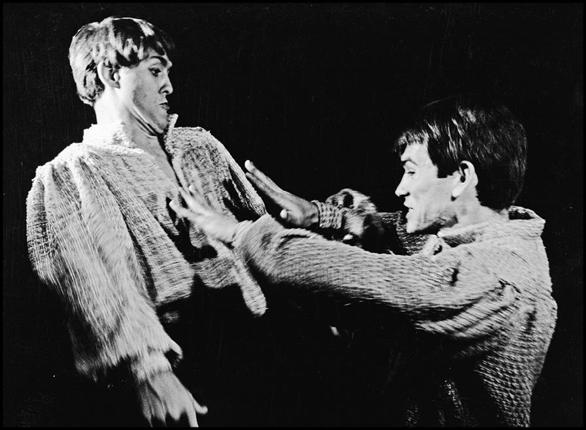

• I played the role of Sparky in

Sergeant Musgrave’s Dance

by John Arden (the title role was played by a student from Texas, a year younger than I, named Tommy Lee Jones).

• I directed John Gay’s

The Beggar’s Opera

in yet another dining hall (the orchestra’s harpsichord was played by future world-class conductor William Christie, and the cast included a talented, bawdy young actress named Stockard Channing).

• I designed the sets for Sean O’Casey’s

The Plough and the Stars

(though in truth they were the ugliest, most ungainly sets ever seen on the Main Stage of the Loeb Drama Center).

• I designed and directed an elaborate production of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck at the Loeb. This is a dark, expressionistic German work, seething with hot-blooded sex, sulphurous jealousy, and murderous vengeance. Although I was a senior by this time and twenty-one years old, I didn’t have a clue about even the most basic of these primal human emotions. But more on that particular blind spot later.

MS Thr 546 (71), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Of the many students swirling around me in those days, several were destined to intersect with my professional life in years to come. One of the actors in that Molière one-act was a fellow named Tim Hunter. He wasn’t much of an actor, but he later became a notable filmmaker and directed me in an episode of the TV drama

Dexter

. The stage manager of every show I directed was a peppy, tart New Yorker named Victoria Traube. Still one of my best friends, she is a longtime executive of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization and an indispensable fixture of the New York theater scene. In my senior year, an eager freshman named Tom Werner arrived on the scene. Although I never knew him at Harvard, years later he too became a good friend. He also became my boss. His company Carsey-Werner produced the six seasons of

3rd Rock from the Sun

for NBC-TV. Also showing up that year was a young would-be journalist who immediately started writing for

The Harvard Crimson

. Before long his gimlet eye would be sizing up my performances on Broadway in his role as drama critic for the

New York Times.

His name was Frank Rich.

But all of these estimable figures in the cultural landscape of the future were happy amateurs like me in those days, with unformed notions of what was to come. We were all fiercely ambitious without being entirely sure what the object of that ambition was. For the moment, we were grabbing at everything Harvard had to offer, unguided missiles trying on different versions of ourselves in an effort to figure out who the hell we really were. True, I was wide open to periodic spasms of insecurity and self-doubt all through those years. But those moments were rare and fleeting. Mostly I was having a wonderful time.

Y

ears later I had a rare opportunity to vicariously recapture the excitement of all that extracurricular activity. In the twenty years after I graduated from Harvard, I had little to do with the place. I rarely even told people that I had gone there. When you are struggling to establish yourself as a working actor—trying out for a soap opera, for example, or for a laxative commercial—you tend to keep a Harvard degree to yourself. But in my forties, in the midst of a thriving acting career, I finally restored the Harvard connection. I was elected to a six-year tenure on Harvard’s Board of Overseers, a thirty-person governing board chosen by the alumni. As the first candidate from the creative arts since Robert Frost in the 1930s, I was a shoo-in. I even outpolled Bishop Desmond Tutu. From 1989 to 1995, I attended seven Cambridge meetings a year, in the company of bankers, lawyers, corporate magnates, college presidents, and senators (among them Tommy Lee Jones’s old roommate, Al Gore). For the first three years of my service I was an empty suit, wondering what in the world I was doing in the company of such movers and shakers.

But then I began to make my presence felt. I embraced my role as “the overseer from the arts.” I launched an initiative on behalf of Harvard undergraduates that, since then, has evolved into an essential Harvard institution. It is called Arts First. It was the best example in my life of the power of a simple idea. Arts First is an annual festival of undergraduate arts, held on the first weekend of every May. It is an exhilarating celebration of springtime, of the completion of the school year, and of youthful creativity and talent. And it is arguably my proudest achievement.

First produced in 1993, halfway through my time as an overseer, Arts First has grown into Harvard’s version of the Edinburgh Festival. By now it is impossible to imagine a year at Harvard without it. During its four-day span, hundreds of students act, dance, sing, play music, exhibit their art, and show their films. Thousands more watch. Every theater and concert hall on the campus is pressed into service. Twenty-odd college buildings are converted to performance spaces. Harvard Yard is flung open to the public and nearly everything is free. And every spring I show up, an eager vicarious participant. Each year, my hair is a little grayer and there’s a little less of it, but my enthusiasm never flags. The students regenerate me. In them, I see my dimly remembered self of many years ago, with all the reckless, inexhaustible excess of youth.

A

nd what about my actual Harvard education?

As a student, let’s just say I was a very good actor. Concurrently with all of my frenzied extracurricular exploits, I managed to fake my way through my studies. I had chosen an extremely rigorous major, English History and Literature. This was an academic field packed with star professors and driven, high-powered students. Although I never completed the reading for a single class and sat mute through most classroom discussions, nobody seemed to notice what a plodding intellectual slowpoke I was.

Oh, but I was crafty. A prime example of my craftiness was an “independent study” I cobbled together for course credit. It focused on London in the eighteenth century, taking Daniel Defoe’s

Journal of the Plague Year

as its central text. To my shame, I never even read the book. My one-on-one teacher was an amiable young assistant professor named David Sachs. The course consisted of three or four pleasant conversations in his office, spread over an entire semester. In years to come, Sachs would achieve a distinguished career in academia. I ran into him by chance a few years ago, and he gently reminded me that I still owed him a paper.

But despite my academic sleight of hand, my distracted brain managed to absorb great swatches of knowledge. Most of my professors were grizzled old superstars of the Harvard firmament who had long since learned how to put on a great show. Lecturing for as many as six hundred students at a time, they were masters at conveying and inspiring a genuine passion for their various subjects. The names of these venerable men barely register now, but in those days they were spoken of around Harvard with solemn reverence. I learned the Homeric epics from John Finley, the history of drama from William Alfred, Romantic poetry from Walter Jackson Bate, art history from Seymour Slive, a smattering of psychology from Erik Erickson, and on and on. And if I did the least possible amount of studying to get by, get by I did. I never got less than a C (and I only got one of those), I wrote a sixty-page honors thesis (on satire in Restoration comedy), I graduated magna cum laude, and I was one of a handful of my classmates inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. On the day I graduated, I secretly felt as if I had gotten away with murder.