Drama (14 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

In the months leading up to our start date, things got a little strange. At the very time that I had begun to cook up a summer theater in Princeton, Tim Mayer had had the much more sensible idea of starting one in Cambridge. Quite naturally, Harvard actors flocked to Tim’s company. As a result, I was hard put to lure anyone to mine. By the time Paul and I had finally assembled our core group, he had enlisted six stalwarts from his New York crowd. I had brought aboard only one actress and a stage manager (the fiercely loyal Vicki Traube). And the Harvard-to-Columbia ratio was about to become even more unbalanced. In the middle of the recruitment process, Paul phoned me from New York with what he considered sensational news. His revered Shakespeare mentor, the great Tony Boyd himself, had agreed to join our company as an actor, and had even condescended to direct our production of

Twelfth Night

. Despite a growing sense of unease, I accepted Boyd’s offer with bovine submissiveness.

The debacle known as “The Great Road Players” unfolded like a ten-car pileup. Sadly, it took much longer.

With Tony Boyd in the title role,

Woyzeck

badly misfired. Its curtain-raiser, “Sweeney Agonistes,” was bewildering. Hardly anyone showed up.

Our board of directors, who had been expecting a palatable season of Shaw, Wilde, and Kaufman and Hart, treated us with withering scorn. They never showed up, either.

The Molière one-acts were diverting and fun, but still nobody came. I took to making curtain speeches, begging the sparse crowds to tell their friends about us.

Staffers from The Princeton Day School angrily complained as we began to leave our messy mark on their pristine theater.

Despite our paltry budget, subsistence salaries, and grab-bag sets, red ink flowed like a river.

The living room of my parents’ home became a crowded war room for our embattled staff. My mother, playing hostess to a second generation of theater lunatics, approached the breaking point.

Tony Boyd revealed himself to be a wildly inconsistent actor and a contempt-spewing megalomaniac. The notion of him directing us in a play was inconceivable to me. I fired him.

I quickly learned that Boyd’s presence in the company had been the principal reason that his devoted students had signed on. When I fired him, they were enraged.

My father offered to bail me out by taking over

Twelfth Night

. I presented the idea in a meeting of the full company. The Columbia contingent mutinied. They screamed invective at me and stormed out.

Two actors got other job offers (or claimed they did) and blithely walked away.

I called a halt to the season with two productions to go. Our tiny pool of subscribers were livid and demanded their money back. What money?

Word reached me from Cambridge, where, in the meantime, Timothy Mayer’s Harvard Dramatic Club Summer Players were in the midst of a triumphant inaugural season.

U

ntil that summer, everything I’d attempted as an actor and as a director had been kissed by success. Not The Great Road Players. It was a total fiasco. Its failure stunned and stupefied me. But it should not have surprised me. In retrospect, the project was fated to collapse. The odds were heavily stacked against us from the outset. I was woefully inexperienced. I had no sense of the challenges of creating a new institution or cultivating an audience. I had no support system beyond a well-meaning but distracted father. I had no leadership skills. I tried to accommodate everyone and recoiled from confrontation. When I hired people, my instincts were abysmal. When I fired them, I waited far too long. These failings, of course, would characterize virtually all twenty-year-old young men, and very few of them would ever put themselves in a position of such responsibility and stress. But I had no such perspective that summer. When The Great Road Players clumsily folded its tents, I could not forgive myself. And if the experience does not quite qualify as a major trauma, it certainly left its mark. I never again attempted to start up a theater company, nor aspired to run one.

B

y then, Jean Taynton had been my girlfriend for a year. She had accompanied me to Princeton that summer. She’d even played a small role in our first show. Through all of my Joblike agonies she had been staunchly in my corner. At that harrowing company meeting when everything fell apart, she was there to witness the insurrection. She even spoke up in an attempt to cool hostilities, bringing down upon herself a volley of angry insults. After the meeting, the two of us sneaked off to lick our wounds, benumbed by all that had gone before. We drove out of town, heading for the Jersey shore. We ate supper in a restaurant and went to see Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn in

Charade

. We did all that we could to put The Great Road Players out of our minds, at least for one evening. I felt comforted, grateful, and deeply attached to her. I’d left my own mother back in Princeton, but I was enfolded in Jean’s maternal love. And eight weeks later, in an Episcopal church service in Philadelphia, with fifty guests in attendance, including the two stricken parents of the groom, I married her.

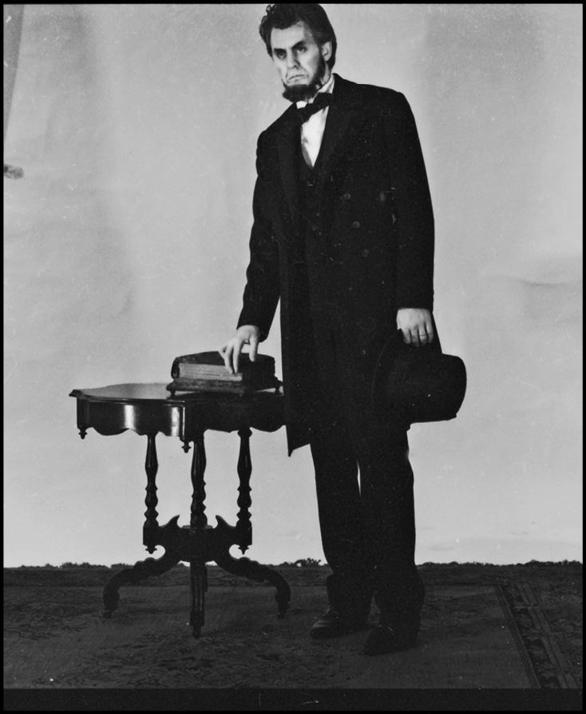

Three Lincolns

MS Thr 546 (155), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

A

t some point, every skinny six-foot-four American character actor is asked to play Abraham Lincoln. I’ve been asked three or four times. The only time I actually did it was in the summer of 1967, when I was twenty-one years old. I had graduated from Harvard and was heading to London in the fall to study acting on a Fulbright grant. I’d decided to stick around Cambridge for the summer prior to my departure, as a member of the Harvard Summer School Repertory Theatre. This was a company run by the professional staff of the Loeb Drama Center and made up of recent graduates of several college drama departments. After the runaway turmoil of the summer before, this job was comfortable and risk-free. (Tim Mayer’s far more raffish and daring troupe, now in its second season, was at the tiny Agassiz Theatre, across the street.) Our Loeb company presented four shows. The last of them was a new play about Abraham Lincoln called

White House Happening

. The writer and director of the play was, surprisingly, the larger-than-life impresario of the New York City Ballet, Lincoln Kirstein. And in Lincoln’s play, I was Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln Kirstein was a mighty figure in American arts and letters, particularly in the world of dance. Over many years he had poured his titanic energies and his considerable fortune into the creation of the New York City Ballet and its feeder institution, the School of American Ballet. He had lured the great choreographer George Balanchine to New York, inviting him to create the repertory of ballets that continues to define the company’s artistic identity. But since I knew precious little about the Manhattan arts scene, and even less about the world of ballet, I’d never heard of Lincoln Kirstein. Months before starting work on his play, I was sent to New York to meet him. It was like making the acquaintance of a turbulent, fast-moving human storm system.

First of all Lincoln Kirstein was big. At six-four, he was my height, but a solid, top-heavy 250 pounds. His wardrobe rarely diverged from a kind of uniform, made up of a navy-blue double-breasted suit, white shirt, black shoes, and dark tie. He was bullet-headed, with his silvery hair clipped to a prickly bristle. His posture was erect but he led with his chin, and his impatient gait always seemed to be just shy of a trot. His intense eyes glinted under a knit brow, and his smile was a grimace, giving him a mischievous, almost satanic air. That year he was sixty years old and at the height of his powers. On my visit to New York he briskly squired me around town, keeping up an animated running commentary on every conceivable subject, ranging far beyond his play. The highlight of the trip was an evening at the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. I sat next to Kirstein for a program of four ballets performed by his company. He was like an emperor proudly displaying his private treasure. At each intermission, he led me backstage, introducing me to the dancers as if they were beloved adopted children. At every moment he was an effusive host, the master of all he surveyed. I was awed and mystified by him in equal measure.

A couple of months later, Kirstein arrived in Cambridge to take charge of rehearsals for the world premiere of his

White House Happening

. The premise of this overheated historical drama is far-fetched and provocative. It proposes that Abraham Lincoln carefully plotted his own assassination. His motive, according to the playwright, was his conviction that the American North needed to make a blood sacrifice to the South to heal the wounds of the Civil War. Kirstein himself seemed utterly convinced of the truth of this wild hypothesis. His play takes place in the White House on the day of Lincoln’s fateful visit to Ford’s Theatre. Surrounding Lincoln is a cast of characters that mixes historical fact and fiction: his wife, a raving-mad Mary Todd Lincoln; his head of the Secret Service, a hand-wringing George Chatterton; his two earnest young aides, John Hay and John Nicolay; and a voodoo-spouting Creole housekeeper. Finally, there is a character that lends a whiff of historical scandal to the proceedings. This is a young mulatto man working as a steward in the White House. The young man is Abe Lincoln’s illegitimate son, born of a long-dead slave girl whom the morose president recalls with moony longing and lip-smacking sensuality. This unsavory historical stew was to be stirred by our writer-director Lincoln Kirstein, who had never directed a play in his event-filled life.

Lincoln directed with the wide-eyed delight of a child with a new toy. He had no conception of the rudiments of staging, and half of our rehearsal time was given over to his long, irrelevant tangents. But none of this mattered to us actors. Nobody could resist the man’s charm, his charisma, and his enthusiasm for the project. Among the cast was Tommy Lee Jones, playing the role of John Hay. Tommy and I were good friends by this time and we watched Lincoln at work with wary admiration and slightly conspiratorial bemusement. Neither of us had ever seen anyone like him.

As the weeks passed and we counted down to our first performance, strange things started to happen. We all watched with growing concern as Lincoln became progressively manic. As the play evolved from its halting first rehearsals to a polished imitation of reality, it seemed to touch some deep well of anxiety in him. One day things reached a tipping point. We arrived for rehearsal that morning, but Lincoln was nowhere to be seen. One hour passed, then two. He finally arrived, bursting into the room with volcanic energy and carrying an open bottle of vodka. He was an alarming sight. His clothes were disheveled, his face was flushed, and his eyes were wild with excitement. He immediately launched into another of his rambling speeches, but this one was fueled by a crazed intensity. As he spoke, he dispensed with his jacket, his tie, even his dress shirt, leaving only a T-shirt covering his massive torso. Every few minutes he swigged from the vodka bottle, emptying it as his company of young actors sat there watching, mute and incredulous.

Lincoln’s speech was wild and disjointed, but we gradually caught the gist of it.

White House Happening

was not about Abraham Lincoln. It was about Lincoln Kirstein. He rattled off the play’s connections to his own life. The mad Mary Todd was his wife, Fidelma; Hay and Nicolay were his extramarital gay infatuations; his black son was Arthur Mitchell, the New York City Ballet dancer whom Lincoln had made into the first great African-American ballet star. And Abraham Lincoln himself was the playwright-director, a haunted, torn, self-destructive creature, struggling to contain his demons. As the production of Lincoln’s play had inexorably taken shape before his eyes, its metaphorical reflection of his own life had become almost unendurable to him. It was pushing him toward a severe psychotic collapse. Listening to his long, tortured outpouring that day, I began to sense how complex my onstage and offstage roles had become. I was Abraham Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln was Lincoln Kirstein, therefore I was Lincoln Kirstein. And in Lincoln Kirstein’s fevered mind, he was gradually losing track of any distinction between the three of us.

Lincoln had lost control. He had been accompanied to Cambridge by an attentive male companion, a man close to his own age named Dan Malone. But not even this kind, solicitous soul could help Lincoln through this terrible crisis. The big man was bewildered and disoriented but full of ferocious, undirected energy. That afternoon he took to the Cambridge streets like an escaped animal, padding around barefoot in that same soiled T-shirt and trousers, with Dan doing his best to steer him clear of trouble.

T

he following day, we witnessed the full force of Lincoln’s mania. We were due to rehearse for the first time on our monumental set. The poor, pitiable man showed up in time for rehearsal, but he looked worse than ever. He was still barefoot, wore the same clothes, and by all appearances had not slept since the day before. When the cast assembled onstage, he ordered us to sit out in the house. For four weeks, we had been performing for him. Now he performed for us. Like a cartoon version of a madman, he acted out a frenzied pantomime. He barked, bellowed, and darted about. He seized a prop knife and whittled away frantically on a wax candle. He dashed behind the scenery, then stuck out his hand, his foot, or his head with jerky, percussive movements. The entire “performance” was agonizing to behold. Tommy Lee and I sat side by side in the theater, stealing looks at each other. No one knew what to do. But something definitely had to be done.

Lincoln appeared to have lost all sense of his own ego. Reminding myself that I was playacting the part of Lincoln Kirstein, I gingerly decided to take on the role of his other self. I stood up, walked forward, climbed up onstage, and spoke quietly to him.

“Lincoln.”

He looked at me as if I had suddenly come into focus.

“Yes?”

“Why don’t we call Dan on the phone?”

“Yes.”

“He can take you to the hotel, and you can have a nap.”

“Yes. Yes.”

His massive body seemed to slump with relief. I got him to the phone, Dan got him to the hotel, and an hour later he was fast asleep. We didn’t see Lincoln again until near the end of the run of his play, about five weeks later. In the meantime, we had learned a bit about his psychological history. Apparently he had experienced a few episodes like this in his adult life, though none nearly as severe or painful. When he reappeared he had lost weight, his hands trembled, his temples were marked with purple bruises, and his manner was tentative, muted, and sweet. Curiously, after all he had been through, he didn’t seem that interested in his own play. But he was grateful and generous to each of us when he came backstage afterwards. Knowing that I was heading off for a year in England, he handed me a stack of letters of introduction to his London friends, including Irene Worth, Cecil Beaton, and Sir John Gielgud.

The director of the Loeb Drama Center had taken over

White House Happening

and we had managed to open with no further mishaps. Despite the passion that Lincoln had poured into the project, it ended up a fairly unremarkable evening in the theater. But for me the experience was overwhelming. It taught me a frightening truth: creating theater, even not very good theater, is like working with volatile chemicals. And in the wrong combination those chemicals can burn you. For the first time I had seen a soul in agony, and that agony had arisen directly from his own emotional investment in the creative process. I had glimpsed real madness, not the pretend kind. And it was all the more poignant and pitiable to see it afflict such a warm, powerful, seemingly indomitable man. This was an acting lesson that couldn’t be taught.

Because of Lincoln Kirstein’s high profile in the cultural landscape of the nation, his play attracted far more attention than it probably should have. Critics flocked up to Cambridge to cover it, and so for the first time in my career I was reviewed in the national press. Lincoln’s notices were mostly dismissive, treating his play as something between a curiosity and a vanity project (to this day, it has never had a second production). As for me, I got one bad review and one good one. The description of me in the pages of

Newsweek

introduced me to the word “neurasthenic.” And the first mention I ever received in the

New York Times

appeared in the last sentence of a negative review written by Daniel Sullivan, their second-string critic:

“The role of Abraham Lincoln is played by John Lithgow, a young man with a future in the theatre.”