Drama (17 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

P

erhaps all of this will explain why I finally returned to Shakespeare a few years ago, at the age of sixty-two. After spurning all those job offers for three decades, I finally received an offer I couldn’t refuse. In the summer of 2007, the Royal Shakespeare Company invited me to come back to England and join them for three months at Stratford-on-Avon. They asked me to play Malvolio in

Twelfth Night

, to reprise the role I’d played as a teenager in Ohio all those years ago, in junior high school assemblies and National Forensic League meets. This was my chance to tread the very boards where I had seen Judi Dench as Hermione, Helen Mirren as Cressida, Kenneth Branagh as Berowne, and where, in its most recent season, Patrick Stewart had played Antony and Ian McKellen had unveiled his King Lear. Forty years after my full-immersion Shakespeare training, here was a chance to finally put it to work. And, more significantly, Malvolio at Stratford was the perfect way for me to memorialize my father, three years after his death.

I took the job in a heartbeat.

And so began my

Twelfth Night

adventure, the most intense déjà vu experience I’ve ever had. On a morning in mid-July, I showed up for London rehearsals at the RSC studios in South Clapham and entered a dreamlike time warp right out of science fiction. Forty years had wrought vast changes in me, but England in 2007 was far more similar than different. And so was the business of putting on plays. From the outset, I felt as if I were reliving an earlier chapter of my own life. The morning tube rides, the drafty rehearsal rooms, the yoga mats, the rehearsal skirts, the chatty green room, the sugary tea, the pints at the pub, and the impulsive evening dashes to West End shows—all of it brought back the sights, sounds, and smells of my days as a young drama student in London, unburdened by the humbling weight of years.

We rehearsed for six weeks in South Clapham before moving up to Stratford, led by our endearing, exotic, comfortably camp director, Neil Bartlett. The first several days of work were given over to exercises, theater games, and improvisations, many of them conducted by RSC voice teachers and movement coaches. For the first two weeks, barely a minute was spent on the play itself. The days virtually duplicated my old LAMDA regimen. It was as if I had never left the place. This was not exactly good news. I began to secretly wonder why I had ever taken the job—wasn’t I a little old for drama school? But if the rehearsals smacked of theatrical boot camp, none of the other company members seemed to mind. Most of them were terrifically talented young actors, willing and eager to try anything. But even the old-timers were game for whatever Neil threw at them. Bit by bit, they brought me around. Neil’s work started to pay off, and my doubts evaporated. I realized that this was exactly what I’d signed up for. Our cast evolved into a strong, sprightly, mutually responsive ensemble, worthy of the company that had hired us. And at last we were ready for Shakespeare.

Twelfth Night

at Stratford was a glorious time for me. During the run of the show, I lived in a tiny row house in Stratford’s “New Town,” two blocks from Shakespeare’s burial place, in Holy Trinity Church. Every day I strolled around town, nostalgically retracing my footsteps from a dozen visits, forty years before. After every show I caroused with the cast at The Dirty Duck, the RSC’s traditional pub of choice. I rented an ancient Morris sedan and spent free afternoons idly exploring the quaint towns and rolling countryside of the English Midlands. I hosted friends, family, and Brit actor pals who trekked up to Stratford to see the play. I even engineered a sentimental sibling reunion with my brother and two sisters, complete with Cotswold picnics, midnight suppers, tipsy reminiscences, and maudlin toasts to our mother and to the memory of our dear, departed dad.

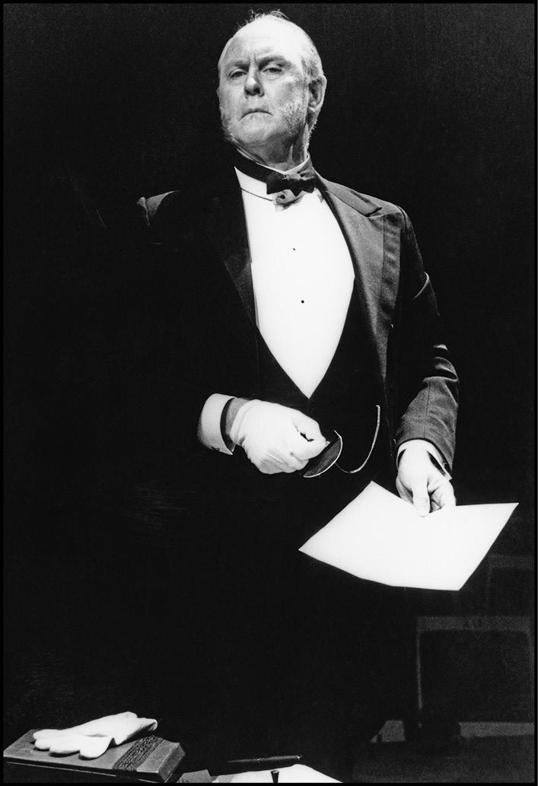

Malcolm Davies Collection © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.

A

nd the production itself? I was crazy about it. Neil had chosen to set

Twelfth Night

in a late-nineteenth-century Gosford Park kind of world. The severe black dresses, swallowtail coats, top hats, and starched collars of the period created an atmosphere of constriction from which the play’s sexual energy and drunken high jinks strained to break free. The comedy was there, of course, but it was shot through with anxiety and pain. As a result, the longing and melancholy of the characters had an unexpected depth. I loved working in these dark colors. Neil’s concept made Malvolio into a stern, dictatorial Edwardian butler, obsessed with protocol and coldly ambitious, a character torn from the pages of Trollope. I embraced this portrait wholeheartedly. My Malvolio was arrogant, judgmental, and sexually repressed, but with a prurient fantasy life. I had little trouble unearthing such strains, buried in my own Puritan nature. When Malvolio is gulled into giving vent to his fettered passions, the moment is wildly comic. But in our version, the joke went much too far. By the end, he had become a broken, vengeful creature, a figure of both pity and danger. Calibrating the stages of this complex comic story was, for me, a fascinating process with a thrilling payoff. After we opened, posters and ads for the production trumpeted a quote from Charles Spencer, the exacting critic from the

Daily Telegraph

. It proclaimed that “the American actor John Lithgow turns out to be one of the greatest Malvolios I have ever seen.”

Every actor savors a rave review, of course. But the

Twelfth Night

experience led to another tribute that I prize even more. By tradition, one of the rooms in The Dirty Duck is informally set aside for actors currently in residence at the RSC. Displayed on the walls of this room are fifty or sixty signed black-and-white photographs. These are portraits of the major actors and actresses who have performed with the company over the last few generations. The photos range from faded, yellowing shots of the young Michael Redgrave and Peggy Ashcroft to more recent glossies of Jeremy Irons, Miranda Richardson, and Ralph Fiennes. Toward the end of my run in Stratford, the owner of The Duck drew me aside and asked me for a signed picture to hang with the others. I was ecstatic. Next morning I urgently sent home for a photo. It arrived the day before we closed. I signed it and ran it over to the pub. I haven’t been back to Stratford since, but I’ve left my mark: mine is the only photograph of an American actor to grace the walls of the Actors’ Bar at The Dirty Duck.

Getting Out

I

n 1968, war was raging in Vietnam, and in the United States all hell was breaking loose. On March 31 of that year, Lyndon Johnson withdrew from the presidential election. Four days later, Martin Luther King was shot, setting off riots in every major city. In June, Bobby Kennedy was shot, too, and in August the Democratic National Convention roiled Chicago. American society was being torn asunder by violent forces of revolution and counterrevolution. This epic drama was fueled by the passions of Black Power and radical youth. Its soundtrack was acid rock and it played out in a haze of tear gas and pot smoke. And there was I, sitting with my wife in a South Kensington mews house and watching all of these dire events being reported in British accents by befuddled newsmen on the BBC. I stared at the evening news every night with a combination of lefty rage and the impotence of a self-exile. What the hell was I doing in

England

?

But my sense of political anger and dislocation wasn’t the only thing unsettling me.

During that time, most young American men in London fell into two groups: the ones who had gotten out of the draft and the ones who hadn’t. The boys in the first group were full of manic, subversive energy. Each had his draft-dodging story to tell, a story that got more elaborate and darkly comic with each retelling. The boys in the second group didn’t laugh at these stories. To them, the draft was not the stuff of comedy. A sullen, haunted look would cloud their faces whenever it was mentioned. Most were in London on student visas for a year of graduate studies. They were serious students, to be sure, but many of them also had an unspoken secondary agenda. They were relying on their studies to keep them out of the army. But the war in Vietnam continued to escalate, and student deferments were not going to last forever. A day of reckoning was approaching for these boys, even the fey young

artistes

in London drama schools. And the draft lay on their shoulders like a heavy weight.

I was in this second group.

In the spring of my D Group year I applied to renew my Fulbright. I couldn’t stay on at LAMDA, as there was no point in repeating a one-year program. But that didn’t stop me from submitting an application. By chance I had spent a few hours in RSC rehearsal rooms during my school year, teaching American accents to the likes of Michael Hordern and Peggy Ashcroft for Peter Hall’s production of Edward Albee’s

A Delicate Balance

. For my Fulbright renewal application, I spun this piddling part-time gig into a proposal to work as an intern or assistant director with London’s major theater companies. Extend my grant, I declared, and I’ll make good use of it. It was a pretty feeble case for renewal, and I didn’t expect it to work, but it was worth a shot. If the U.S. government was willing to continue supporting my studies in England, I figured there was no way it would send me to fight in Vietnam. To my amazement, my Fulbright was renewed. To my dismay, halfway through my second year in London, I was drafted anyway.

I had registered for the draft in Trenton, New Jersey, when I was eighteen years old. At that time, only a tiny fraction of the U.S. population had ever heard of Vietnam. I had filled out a form that included a question asking if there was any reason I should not serve in the American military. I had loftily written that I “disapproved of war as a means to settle disagreements between nations,” or words to that effect. This had been my only gesture toward earning myself conscientious-objector status. And four years later, at the height of the Vietnam conflict, with 500,000 American soldiers stationed there and thousands more being conscripted every day, that arch sentence had clearly made no impression on the Trenton draft board. A formal notification arrived at my London address, forwarded to me by my parents. It ordered me to report for a draft physical in Trenton, assigning me a date and time a few weeks hence.

I was barely ruffled. I fired off a letter to the draft board in response, confident that it would get me off the hook. The letter was bold and indignant, but my arguments against being inducted were absurdly thin. I firmly stated that I could not possibly show up in Trenton on the date assigned. I was in England, after all, on a U.S. government grant. I told them I was an assistant director on an important new play at the Royal Court Theatre in London, working with a core group of disciples of the great Peter Brook. On the ridiculous assumption that the name Peter Brook would mean anything at all to the Trenton draft board, I enclosed a letter from him claiming that I was “indispensable” to the project (this, notwithstanding the fact that I had never met the man). I even reminded the board of my watery antiwar protestations, written on that registration form six years before. In retrospect, I picture a table in an office in Trenton, New Jersey, surrounded by staffers from the Selective Service System, reading a letter out loud from a Fulbright scholar in England and sharing a good hearty horselaugh before tossing it in the wastebasket.

Shortly afterwards I heard from Trenton again. Once again I was given a date and time for my draft physical, but this time I was told to report to a U.S. Air Force facility, situated on an RAF air base just outside of London. This time I was scared.

In desperation, I decided to fake my way out of the army. With a combination of political self-righteousness and creative zeal (and a healthy dose of fear and cowardice), I set out to forge my most challenging, complex, and subtle performance to date. I would play the role of John Lithgow, but I would play him as an unrecruitable psychological basket case. For this particular piece of playacting, I would put aside the rigorous precepts of my LAMDA training and adopt my own half-baked version of the Method. I would forsake stage technique for sense memory and emotional truth. And I would play my part as if my life depended on it.

My basic approach was to create a heightened version of my darker self. In the week leading up to my physical, I lived the life of another person. Everything I did was a perversion of my customary behavior. I barely ate and barely slept. I went unshaven and unbathed. I picked my face and peed on my own fetid undershorts. One afternoon, I sat in the dark in a near-empty Soho strip club with a couple of furtive old men, staring at the desultory, sexless performance of a po-faced stripper who might have stepped out of a Diane Arbus photograph. By such means, I struggled to induce in myself a feverish state of anxiety, depression, and near-madness. And it worked. On the morning I reported for my physical, I was an ashen, quivering, foul-smelling mess. I had scrupulously rehearsed for a week, and now I was ready to perform.

My goal was to fool the military into thinking I was unfit for service. In fact, circumstances made it far easier for me to achieve this goal than I could have hoped. Since the physical was being conducted at an Air Force facility by Air Force personnel, no one had any particular stake in whether or not I was inducted into the U.S. Army. Everyone involved in my exam seemed bored and offhand, making no effort whatsoever to see through my act. My red eyes drooped with fatigue and my hands trembled as I filled out forms. I even fainted dead away when my blood was drawn. But none of this artifice raised the slightest suspicion among my examiners, or even much interest. They simply wrote down a description of whatever they saw, ready to send it back to Trenton as observable fact.

After completing my battery of tests, I was singled out for one more interview. I was ushered into the office of an Air Force psychiatrist. He was the only person I dealt with that morning who appeared to be seriously engaged in his duties. He was kindly and soft-spoken, an earnest young man with a distinctly unmilitary aura of compassion about him. He gently questioned me about my psychological state, and I was ready for him. In the weeks leading up to this interview, I had created a detailed psychological profile of myself. I now laid it out for this young man without making a single false statement. I had taken mildly neurotic aspects of my own nature and inflated them into full-blown psychosis. My garden-variety shyness was now pathological fear. My tendency to avoid confrontation was now a phobic terror of violent conflict. My scanty sexual experience was now a tormenting doubt about my manhood. When he asked me straightforwardly if I was homosexual, I obliquely replied that, in spite of my marriage, I often thought about my college roommate. As we spoke, he took down detailed notes, entirely persuaded. I was acting for an audience of one, and he had no idea that I was acting. This made my session with him the most convincing performance I’d ever given. A triumph! But I took no joy in it. The man was filled with such empathy and understanding that I actually felt bad for him. My self-contempt bloomed like a poisonous flower. Ironically, this only deepened my performance.

A month later, another letter from the Trenton draft board was forwarded to me in London. The reviews were in. I was a smash. They classified me 4-F. This was the Holy Grail of the antiwar generation. I would not be drafted.

T

hat year, Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant” was a huge hit in the United States. The song was a loopy anthem for the antiwar youth of America. It tells the story of Guthrie’s attempts to get out of the army by faking his way through his draft physical. It is a farce version of exactly what I went through in London that very year (and, by coincidence, much of it was set in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, one of my many hometowns). The tone of the song is comical and carefree. For Guthrie, dodging the draft was a clownish lark, a cause for celebration, and the raw material for a hit song. This was not my experience. I never regaled anybody with my draft story, nor ever dreamed of making it a public entertainment. Indeed, this is the first time I’ve ever told it. A sense of shame stayed with me for years and has never entirely disappeared. Some of that shame had to do with the appalling suffering caused by the Vietnam War, suffering that I so conveniently avoided. Some of it had to do with the fact that I showed so little courage and conviction in protesting the war and that I spent two of its most turbulent years leading a comfortable, fun life in swinging London.

But somewhere deep down there was another source of my shame. I didn’t get out of the army by acting. I got out by lying. There is a difference. When you act, you do it for a willing audience, ready and eager to be tricked into belief by a crafty imitation of reality. There is an unwritten pact between an actor and his audience: I will deceive you but I will do it for your delight, your edification, or your illumination. And I’ll only do it if you so desire. On that Air Force base I was violating that pact. Until then, I had always thought of acting as an art—a slightly tainted, highly suspect art perhaps, but an art nonetheless. The events of that morning troubled me deeply. If acting was an art, I had abused it. The concerned face of that Air Force shrink stayed with me. He wrote down my fake ailments without a trace of skepticism or doubt. As he did so, I was overwhelmed with relief. But at the same time, shame was churning inside of me.