Drama (5 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

I

n the summer following my sixth-grade year I began to sense that something strange was going on. Whatever it was, it had taken me a long time to detect it. Looking back, I realize that my parents must have been living through a period of queasy anxiety, both in Stockbridge and in Yellow Springs. But they had a kind of genius for concealing this fact from their children. For my part, I must have been equally ingenious at ignoring their signs of stress.

The only evidence that anything was wrong was the fact that we kept relocating to different parts of town, house-sitting in other people’s homes. For years we had lived in our own big, beloved ramble on Dayton Street, full of our own comfy, well-worn furniture. The house was the ideal small-town manse, with a broad front porch and a porch swing. It was shaded by a giant oak, and surrounded by fruit trees, peony bushes, and my father’s splendid grape arbor. A weathered barn stood off by itself, but it was nothing more than a vast playhouse for us kids. An old jalopy was propped up on cinder blocks on the barn’s dirt floor. My parents had bought it for my big brother David to indulge his passion for tinkering with engines. All of these childhood glories were suddenly relics of the past and the stuff of nostalgic memory. I don’t remember ever asking why. Apparently, I was perfectly content to pack up and move on, three times in one year, to strange homes whose owners had temporarily left the premises, to do research, take a sabbatical, or get a divorce.

The last of these places was the most unlikely. We all crowded into a few rooms on the second floor of a farmhouse outside of town. It was August, weeks before the start of school. My family must have been floating in limbo, but, ever the cockeyed optimist, I was oblivious. I was having a wonderful time! With my equally adventurous big sister, I explored empty silos, cluttered toolsheds, groves of trees on the edge of vast cornfields, and a clear, swimmable creek.

For those weeks, Robin and I were billeted in the same bedroom. One night we were idly playing a board game, laughing and chatting with the radio on in the background. Paul Anka reached the end of “Diana,” and the local news came on. Robin and I were barely listening until we heard our father’s name. Our heads jerked up from the game, we caught each other’s eyes, and heard the announcer’s voice state that Arthur Lithgow had resigned from Antioch College and would leave his longtime position as managing director of the Antioch Shakespeare Festival.

My response to this news was inane: I was thrilled that my own father merited such attention on a radio broadcast. My older and wiser sister must have realized that the news was not good. In an instant, our lives had changed irrevocably, and not for the better. My childhood in the midwestern Eden of Yellow Springs, Ohio, was over. I was now destined to receive the best training any young actor could ever have. I had been cast as “the new kid in town,” and I would play the role, over and over again, for the next decade of my life.

A Kiss on the Neck

W

hat in the world were we doing in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts, on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, a week after Labor Day, in September of 1957? Every year, at the moment the summer season ends, the Vineyard becomes almost ghostly. Its population plummets and almost all of the Cape Cod gingerbread homes are boarded up. In the towns, the streets are eerily empty. The carousel in Oak Bluffs is shuttered and silent. As the days pass, all signs of human life disappear from the windswept beaches, leaving them desolate and melancholy. Even the water in the ocean seems to turn gray. Why move to Oak Bluffs? And why at such a dispiriting time of the year?

There was a reason, but it was a strange one. Seven years before, my father had banded together with a troupe of young actors to present a festival of plays by George Bernard Shaw, in a shabby little summer stock playhouse in the piney woods of East Chop, on the outskirts of Oak Bluffs. Toward the end of that summer, a waspy summer resident from nearby approached Dad as he sat in front of his makeup mirror, preparing to go on in

The Devil’s Disciple

. The man offered Dad the chance to buy a rambling five-bedroom vacation home near the playhouse. The price was astoundingly low. Dad jumped at the opportunity, thinking that such a house could serve as the perfect dormitory for his acting company the following summer. He never paused to ask himself why the house was so cheap. Only later did he learn that the residents of East Chop had conspired to lure lily-white neighbors into their midst. This was their ignoble attempt to fend off an incursion of middle-class African-American homebuyers. The attempt failed: in the last fifty years, Oak Bluffs has grown into one of the largest communities of vacationing black families in the United States.

As it turned out, Dad’s impetuous purchase had been woefully misguided. “The following summer” never came. Instead of a Shaw festival on Martha’s Vineyard, he started the Shakespeare Festival in Yellow Springs, which would consume his summers for the next several years. As a result, we were the proud owners of a vacation home on Martha’s Vineyard, for no good reason at all. In all those years, I can only recall one actual summer vacation there, which lasted about a week. I remember an untended front yard of knee-high, straw-colored grass, wicker furniture creaking from old age, the smell of disuse in all of the rooms, and the queasy feeling that we were poor relations visiting someone else’s estate.

Our first and only extended stay in the house began in 1957, the year in question. When Dad precipitously quit Antioch, we had nowhere else to go. Bidding farewell to uncomprehending friends, we bolted from Yellow Springs and headed for Oak Bluffs, where the mournful, untenanted house sat waiting for us. Our sole purpose for moving there was to sell the place and plot our next move. With forced cheeriness, my sister and I picked out our bedrooms, settling into a drafty summer home for the cold months of a New England seacoast fall and winter. Dad sealed off half of the house with wallboard and mastered the workings of the big coal furnace in the basement, which roared to life after decades of idleness.

If I felt out of place in our huge saltbox manse, imagine my sense of dislocation in the Oak Bluffs public school. My classmates were the children of Martha’s Vineyard year-rounders, a multiethnic mixed bag of fishermen and service-sector workers who catered to the recently departed population of vacationing rich folks. Half of my seventh-grade class had the last name of DeBetancourt, all of them descended from generations of Portuguese emigrants. The class was blessedly small. As an exotic newcomer, I was welcomed into their midst with a mixture of suspicion and offhand curiosity. Why had I arrived in Oak Bluffs at that time of year, when everyone like me had just left town on the last Labor Day ferry? I didn’t even try to explain it. I barely understood it myself.

Our teacher was a tall, angular man in his forties named Mr. Troy. Looking back, I can’t imagine what he was doing there. He was charismatic, intelligent, intense, and cynical, clearly overqualified to teach this roomful of ragamuffins. He would hammer their lessons into them and ruthlessly mock them when the information didn’t stick. The class would respond to his mockery with squeals of delight—what did they care? One especially thick-headed student named Crosly sat next to me at the back of the room. Pasty and lubberly, he liked to twist his great bulk around in his seat and try to kill flies on the floor by smacking at them with a ruler: clack, clack, clack. One day Mr. Troy lost patience with this and, in an electrifying moment, interrupted our math lesson by hurling an eraser the entire length of the room, squarely nailing Crosly in the middle of his broad, fat back. The class cheered maniacally.

My mother and father dutifully showed up at school for Parents’ Night, halfway through the fall semester. Afterwards, with hilarity shot through with guilt, Mom described their parent-teacher conference. Mr. Troy had kept the meeting short and to the point. Forgoing any introductory remarks, he had simply exclaimed, “Get him out of here!”

That December, I went to a school dance in the gymnasium. By this time, I had managed to work my way into the good graces of the seventh-grade Oak Bluffs “in” crowd (such as it was). I had accomplished this mainly by befriending the brawny, black-leather-jacketed class tough, Ashley DePriest, and by accepting his offer of my first cigarette. I got along fine, too, with the loud, raunchy girls who turned up the heat in all the flirty sexual interactions of our class. But although my hormones were approaching the boiling point, I was still the shy new kid in town and nowhere near secure enough to act on even the most chaste of my impulses.

So imagine my astonishment at the school dance when scrawny, bespectacled, and wildly sexy Ruthie Legg attacked me from behind, wrapped her arms around me, planted a moist, lipsticked kiss on my neck, and then ran back to a shrieking gaggle of girls, having made good on a dare. A glandular explosion erupted inside me. A breathtaking revelation almost caused me to faint: I was the object of a group crush! Impossible but true! I was attractive! Maybe life in Oak Bluffs was not the cold, barren tundra I had made it out to be.

T

wo weeks after this intoxicating episode, I was gone. The Lithgow family abruptly packed up and left Martha’s Vineyard behind them. Unbeknownst to me, my parents had sold our house and engineered our next move. We were heading to a small town on the Maumee River in northern Ohio, a move just as bewildering as the one before. I never saw any of my Oak Bluffs classmates again. None of them, that is, except one.

A crazy-quilt history like mine generates some astonishing coincidences. Fifteen years after my strange Martha’s Vineyard adventure, I found myself in New York City, a twenty-six-year-old unemployed actor, married, with a six-month-old baby boy. A friend invited me to direct two plays in a summer-stock theater he had founded a year before. The theater was situated in the gymnasium of the public school in the town of Oak Bluffs, on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. Stunned by the coincidence, and grateful for any work at all, I accepted. As I walked into that gym, utterly unchanged in all those years, I headed straight for the spot where Ruthie Legg had jumped me from behind. I stood there for a long moment, savoring the rich, exquisitely painful irony of life.

On the day I left Martha’s Vineyard, having finished my work on both of my shows, I sat with my wife and baby in the Black Dog Tavern in Vineyard Haven, waiting for the ferry to the mainland. During my month on the island, I had searched the faces of everyone I passed, hoping to catch sight of one of those long-lost classmates from Mr. Troy’s seventh grade. I had spotted no one. But on this morning, looking across the tables of the Black Dog, I recognized a large man in a mechanic’s monkey suit leaning over a cup of coffee. He had greasy blond hair combed into a fifties-style ducktail. He smoked a cigarette. Except for a droopy mustache, he had not changed in fifteen years. I walked over to him.

“Excuse me,” I said, “but aren’t you Ashley?”

Silence.

“Ashley DePriest?”

“Yuh.”

“This is incredible. I’m John. John Lithgow. You gave me my first cigarette.”

More silence.

“From Mr. Troy’s class. Seventh grade, remember? With Debbie DeBetancourt? Denny Gonsalves? Ruthie Legg?”

Ashley DePriest looked at me with bleary blue eyes, expressionless.

“I remember all of

them

. But I don’t remember

you

.”

Not remember!? How was that possible? Had all of these people, so vivid in my memory, retained no image of me at all? Had I simply slipped in and out of their lives, a forgettable minor player? Had Ruthie Legg forgotten, too? For the first four months of seventh grade, I had desperately struggled to overcome my fear, to assert myself, to fit in. In my own mind, I had been a nervous, untested young actor, gradually winning over his toughest crowd. That morning, Ashley DePriest was my most dismissive critic. I had been completely unmemorable.

Lachryphobia

A

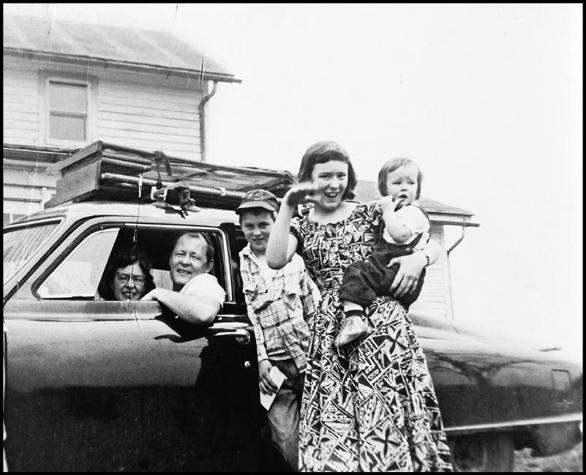

s I recall it, the drive from downtown Toledo to the town of Waterville takes about a half hour. There were five of us in the car when I first took that short trip. My father, my mother, and my baby sister were escorting my big sister and me to our first day of school. It was halfway through the school year, and Robin and I were sick with anxiety. The January day was clear but brutally cold, with gusts of snow snapping across the flat, brown fields. By some innate wizardry, my mother had managed to secure yet another big house for us to live in, but we couldn’t move into it just yet. For now we were billeted in a Toledo hotel, hence the January commute. On the radio, Buddy Holly was singing “Peggy Sue.” I remember listening with intense concentration, mentally reassuring myself. “I know this song,” I thought. “I’ll have something in common with them.”

So began the next chapter of the cockeyed story of my teenage years. My father was attempting to relaunch his summer Shakespeare Festival in a new setting. This time, the actors would perform in the outdoor Toledo Zoo Amphitheatre, where, in years past, the Antioch company had made frequent guest appearances, to the roars of lions and the shrieks of peacocks. He had five months to gear up for the summer season, and the sleepy town of Waterville was to be our bedroom community.

Joining a second seventh-grade class was bad enough. But joining it in the middle of the year was horrific. The small measure of confidence I had achieved in Oak Bluffs had vanished. My twelve-year-old’s self-esteem had dropped to zero. I felt like I had been sent back to square one. In retrospect, my situation was hardly the stuff of a severe childhood trauma. There was nothing to fear from my cheerful, milk-fed new classmates, many of them sturdy farm kids with names like Weimer, Marcinek, Scheiderer, and Hiltabiddle. But I was terrified nonetheless. The causes were twofold: I was desperately afraid I would burst into tears (which occurred five or six times in the first week) and that someone would notice one of my inexplicable erections (which occurred every twenty minutes). I was a mess.

The fear of tears was a real problem. Call it lachryphobia. I simply couldn’t get to the end of a day without crying, and every time it happened I was mortified with embarrassment. For example, I recall a halting conversation with a pleasant fellow named Denny Bucher across our lunch trays in the school cafeteria. In an act of almost corny kindliness, he asked me what Santa Claus had brought me for Christmas. His simple solicitude opened a floodgate of maudlin self-pity in me. I exploded with sobs in front of everyone, spilling tears and snot all over my chipped beef and biscuits.

By an uncanny maternal intuition, my mother sensed what was going on. Her response was swift and pragmatic. Behind the scenes, she arranged for me to simply walk home for lunch every day. Fortified by that daily half hour at our own kitchen table, I gradually got my sea legs and once again began to adapt. My first full day of school with no tears was a pathetically small victory, but a victory nonetheless. Within weeks I had collected a few friends, unveiled my nascent sense of humor, and put my days of lachryphobic geekiness behind me. As the winter weather gradually gave way to spring, my spirits continued to improve. Just as I had blended in with the deracinated young delinquents of Oak Bluffs, I now joined the wholesome ranks of Waterville’s backyard boys and girls: riding bikes, flying kites, and playing intense rounds of kick-the-can until nightfall. I even spent weeks building a bright-red ersatz Soap Box Derby racer. My friends and I pushed each other around in it, up and down the leafy sidewalks of Waterville, hour after idle hour on end.

O

ne evening that spring my father had something to show us. He had worked all day on a brochure to announce his upcoming summer season of plays. Using pen and ink, he had hand-lettered all the information in the brochure and created ink drawings to illustrate it. The drawings depicted scenes from each of five plays–

The Tempest

,

Charley’s Aunt

,

The Devil’s Disciple

,

Ah, Wilderness!

, and something called

Pictures in the Hallway

, billed as “a new play” adapted from the prose writings of Sean O’Casey. Dad was visibly proud of his own handiwork, and I recall being pretty impressed by it, too. I don’t remember the slightest concern that the brochure looked cheap and amateurish. But in retrospect I can picture it vividly, and it did.

That evening, I didn’t think to ask myself any of the questions that seem so obvious to me now. Why was my father making his own brochure? Why was he doing it on the kitchen table? Why did my mother have that anxious, skeptical look on her face? Why was there only one Shakespeare play included among the five offerings? And why were the plays going to be presented in the small indoor theater adjoining the Zoo Amphitheatre, and not in the huge Amphitheatre itself? And the biggest question of all didn’t even occur to me: “Is anything wrong?”

There was plenty wrong. But, typically, my parents shared none of it with their kids. Years later, when my father was an old man, he told me the events of that year from his point of view. I finally learned what he and my mother had so expertly kept from me while it was actually going on.

Originally, the summer season was to be sponsored in large part by Toledo’s major newspaper,

The Blade

. Assured of their backing, Dad had posted an “Equity bond” and had engaged a company of actors, signing their contracts himself. Almost all of these actors were friends and veterans of his former Shakespeare Festival. The new festival was to be precisely modeled on the old one, even using its distinctive unit stage design. Continuity was everything. He planned to capitalize on the reputation of the old festival and retain its huge following, both in Ohio and in neighboring states.

As it happened, my father relied too heavily on his own optimism and the good faith of his backers. To his shock and dismay,

The Blade

withdrew its funding, but too late for him to cancel the season. He was trapped, both by legal obligations and loyalty to his long-time troupe of actors. With a fraction of his projected budget and a stack of signed contracts on file, he had to come up with an alternative plan in a matter of days, and it had to be cheap. Hence the smaller theater, the shorter list of plays, and the tacky brochure on the kitchen table. The season went forward, and if memory serves, the shows were pretty good. But nobody came. By mid-August, my father’s last-minute summer theater festival was a slowly unfolding catastrophe. But as the clouds gathered, I was blithely oblivious. My summer days were spent swimming at the quarry outside of town, and my evenings were devoted to playing third base for the Indians of the Waterville Little League.

Not once did I notice, even for a second, that both my parents had been seized by desperate panic. As Dad told the story in old age, the acute anxiety of those days still had the power to unsettle him. The fact was that by the end of that summer, he was in serious trouble. As a manager and businessman, he had always been vague and haphazard. But this time, with no one to look after the books, his negligence had caught up with him. In struggling to keep the company afloat, he had played fast and loose with payroll taxes. The season was drawing to a close. The festival was a washout. My parents were broke. Creditors were clamoring. Auditors were converging. In a nightmare scenario, Dad saw himself frogwalked to prison by the Feds, leaving his penniless family behind him.

At this juncture, a deus ex machina appeared in the form of a man named Hans Maeder. Maeder was the cheerfully despotic German headmaster of The Stockbridge School. This was a boarding school near Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the town where I had spent fifth grade. My brother David was just about to graduate from the school, having lived there for the previous three years (hence avoiding the mad vicissitudes of our recent moves). Out of the blue, Herr Maeder offered my father a job teaching English and drama. He even threw in a spousal appointment for my mom as a school librarian.

For my panicky parents, this dual offer was a lifesaver. They accepted it, but not before huddling with the Toledo festival’s legal counsel. This man assured my father that he would find a way to clean up the financial mess that Dad had left behind. But at the same time, he urged Dad to get out of town as fast as he could. And so, as if grabbing the caboose railing on the last train out of the state, we loaded up our black Studebaker sedan and sped away.

For the second time in a year, I left behind a hard-won community of friends whom I would never see again. But this time, the change would be less of an adjustment, and far less wrenching. In Stockbridge, I would rejoin my old fifth-grade class from three years before. Familiar teachers, schoolmates, playmates, and crushes were all there, waiting for me, three years older. This would not be so bad.

Try as I may, I can’t picture the moment when my parents announced this most recent disruption. I can’t recall my reaction to the news, nor my emotional state of mind as we watched Waterville disappear in the rearview mirror. But I can guess. I imagine that I was not so fearful this time, not so confused, not so resentful. I was heading back to Stockbridge, a world I knew and liked. And Waterville, like Oak Bluffs before it, represented a modest personal triumph, a hurdle I had cleared, a battlefield where, thirteen years old, I had emerged unscathed. I suspect that I felt pretty good. I was getting better at this.