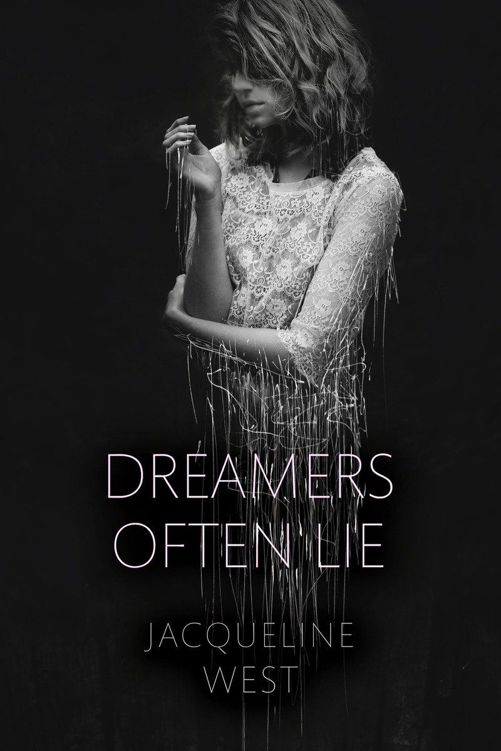

Dreamers Often Lie

Read Dreamers Often Lie Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

D

IAL

B

OOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

Copyright © 2016 by Jacqueline West.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

eBook ISBN 9780698407886

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: West, Jacqueline, date, author.

Title: Dreamers often lie / Jacqueline West.

Description: New York, NY : Dial Books, [2016] | Summary: “After waking up in the hospital, Jaye returns to school to discover a mysteriously familiar boy in her class and the trappings of Shakespeare’s plays all around her” — Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015031235 | ISBN 9780803738638 (hardback)

Subjects: | CYAC: Love—Fiction. | Brain damage—Fiction. | Theater—Fiction. | Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616—Fiction. | BISAC: JUVENILE FICTION / Love & Romance. | JUVENILE FICTION / Social Issues / Depression & Mental Illness. | JUVENILE FICTION / Performing Arts / Theater.

Classification: LCC PZ7.W51776 Dr 2016 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015031235

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters. places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Jacket photo © 2016 by Rachel Baran

Jacket design by Maggie Olson

Version_1

For Ryan

R

OMEO:

I dreamt a dream tonight.

M

ER

CUTIO:

And so did I.

R

OMEO:

Well, what was yours?

M

ERCUT

IO:

That dreamers often lie.

—

Romeo and Juliet,

A

CT

I

,

S

CENE

IV

T

here was blood on the snow.

White, with a smattering of red. Like petals.

One petal was stuck to my lips. I could feel it dissolving with my breath, its rusty sweetness coating my tongue.

My cheek hurt. Everything hurt.

And the sun was too bright. It seared through my eyelids, making my whole skull clench. I tried to turn my face away, but I couldn’t. I tested my fingers, my feet. Nothing moved. Maybe it was the cold, or the tight-packed snow, or that I felt only halfway inside of myself, like my body was a costume I hadn’t finished putting on. I just kept still, watching as the roses bloomed through the whiteness around me, their red petals growing larger.

I don’t know how long I’d been lying there when someone lifted my hand.

I squinted up.

Flares of sun erased his edges. I could make out a pair of pale eyes. Tangled black hair. The brightness made my head pound.

What’s going on?

I tried to ask.

How did we get here? Why is half of my face on fire?

But all that came out was a groan.

“She speaks!” His voice was deep and warm. “Oh, speak again, bright angel!”

No one with blue eyes and tousled black hair had ever called me an angel.

Wait—I knew that line. Was this a play? Were we rehearsing something?

He was still holding my hand.

I blinked up at him as he raised my hand to his lips and kissed the back of my wrist.

That’s nice,

I thought.

Old-fashioned. A little dramatic. But nice.

And there was something familiar about it. We must have practiced this before.

The world went diamond-bright and silent. My cue. What was my line? I scrambled after the thread of it.

Stay— Stay—

Something about hands. Something about light.

My arm settled back into the snow.

Too late. He was already gone.

Scene over.

The smell of roses grew stronger. The ground sagged, the whiteness sinking until the hole around me was so deep that it took a whole crowd to hoist me out.

Jaye,

said a new voice.

Stay with me.

Lots of hands lifted me. Lots of hands laid me down.

The place where they put me was thin and hard and narrow. It rattled as they rushed it over the snow. What scene was this? What was I supposed to do now?

A metal door slammed.

The white sun switched off and a red light switched on. It spun like a spoon in a glass full of blood.

Jaye

.

Come on, Jaye. Stay with me.

A knot of people twisted around me, faces looming closer, disappearing. The ground beneath me roared. Something in my head roared with it.

Hang on, Jaye. Stay with me.

But the cold had snipped and sliced at me until there was nothing left to feel it.

The petals rained over me, red and weightless.

I closed my eyes.

They buried me.

M

y eyes started to open without my permission.

I fought to keep them shut. The second I opened them, I’d be sucked up into the tooth-brushing, clothes-finding rush to school, searching for my algebra textbook, remembering the assignment I’d skipped when I got caught up in the Hitchcock marathon on AMC. By the time I staggered downstairs, everyone else would be dressed, flushed and glowing from their early-morning runs and showers, and I’d still have pillow creases on my face and a flat spot in my hair.

I tried to wriggle down into my rumpled purple quilt.

But this morning, the quilt was tucked with weird severity across my chest. And someone—probably Mom—had already come into my room and opened the thick velvet curtains I’d made with scraps from the costume shop.

Mom must have turned on the lights too, which meant I’d

really

overslept. The glow that fell over me wasn’t the chilly blue of dawn. It wasn’t even the paler blue that meant I’d already hit snooze twice. This light was yellow

and electric and ugly, and it was prying at my eyelids like a butter knife.

I flung out a hand and groped for the alarm.

But the alarm hadn’t buzzed.

And my arm didn’t move.

I opened my eyes.

This was definitely not my bedroom.

This room was spotless. Its tile floor gleamed. Its windows sparkled behind half-closed blinds. The walls were bare. No theater posters, no doodles, no collages of ticket stubs and quotes from Ibsen and Tennessee Williams. The sheets around me were as clean as printer paper. Everything was coated with that ugly yellow light.

That light. And that smell.

I knew that smell.

Liquid soap. Rubbing alcohol. Bodies.

Bodies that leaked and sweated and bled things that should have been kept sealed inside.

The hospital smell.

My throat constricted.

In the usual nightmare, I’d be running through the maze of hospital halls, veering around corners, looking desperately for the right room. Sometimes, just as I spotted the door, a blockade of nurses would appear and tell me that only family was allowed inside, and when I said I

was

family, no one would believe me. Sometimes I never found

the door at all. I always woke from these dreams with my legs cramped and tired, my heart pounding.

But this time, I was the one in the bed.

This time, the needle was in my arm. The machines beeped along to my own pulse.

This was wrong. This made no sense.

Might as well sink deeper and start again.

The darkness lashed out. It wound around me, tightening, pulling. I felt the bed tilt, my head rising, feet falling, until I slid straight out of the sheets into something covered in prickly upholstery.

When I looked up again, a long, empty stage stretched in front of me. Its red velvet curtains were bleached by the beam of a spotlight.

Yes.

Yes.

This was where I was meant to be. In the high school auditorium, waiting for rehearsal to start.

The panic of the dream flowed out of me. Happiness gushed into its place, bringing everything else with it. The sight of the cast list.

TITANIA, the FAIRY QUEEN—Jaye Stuart

printed there in big black letters, and still I had to read it six times to believe it. The sensation of the battered paperback script in my hands, all my gorgeous lines highlighted in ribbons of green ink.

I bounced in the creaky seat.

Where was everybody?

Tom and Nikki almost always beat me to the auditorium. By the time I got here, they’d be deep in some project, sketching makeup designs, arguing over the pronunciation of the word

zounds

. Crew members came even earlier, opening the curtains, flipping on the work lights. But now there was no one.

I craned around. Behind me, rows of empty seats dwindled upward into shadows. Except for that single burning spotlight, the entire house was dark. I was about to get up for a better look around when there was a soft creak to my left.

I turned, expecting to see Nikki or Tom. Maybe Anders or Hannah. Some other friend.

Not Pierce Caplan,

I told myself, before the beating in my chest could get too hopeful.

Don’t even think about Pierce Caplan.

But the person in the next seat wasn’t anyone I knew.

I recognized him anyway.

He had sunken cheeks, and a sharp, stubbly jaw. His hair looked like it had been through several nights of bad sleep. He was dressed all in black, so every part of him but his head and his hands seemed to seep into the surrounding dimness. There was a prop human skull in his lap.

He stared straight at me.

“Hello,” I said slowly.

“Hello.” Hamlet’s voice was low and polite. “Are you here for the play?”

“For rehearsal? Yes. But we’re doing

A Midsummer

Night’s Dream.

” I glanced down at the yellowish skull. “I think you’re waiting for the wrong show.”

He shook his head. “I’m only here to watch.”

“Oh.” I pulled my eyes away from the skull. “Well, we’re just getting started, so there won’t be much to see. Unless you really love high school drama.” I smiled. “The offstage kind, I mean.”

Hamlet didn’t smile back. “How so?”

“The usual stupidness. Someone likes someone who doesn’t like them back. Somebody gets a part that somebody else wanted. A bunch of the senior girls are mad that a junior—meaning me—gets to play Titania. A bunch of the theater kids are mad that a guy who’s never done a play before gets to be Oberon . . .”

“But you are not mad.”

“Me?” I turned to face him head-on. Hamlet’s eyes were like cracked ice. “Not really. No.”

“No.” Now Hamlet began to smile. It was a knowing, lopsided smile. It made the skin of my arms prickle. “Why should Titania cross her Oberon?”

I’ve honed a giant repertoire of expressions in my bedroom mirror.

Morose. Effervescent. Smitten. Terrified.

I can leap from one end of the spectrum to the other, pull off layers of strange combinations. It’s like having a thousand disguises that I can take with me anywhere. Now I smoothed my face into my innocent/nonchalant expression, the expression that said I didn’t care that Pierce

Caplan—perfect, golden, untouchable Pierce—was playing my husband in

A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

“We should really be getting started,” I said. “I wonder where everybody is . . .”

I craned around to search the house again. I could still feel Hamlet’s cracked-ice stare numbing my skin. I didn’t think he had blinked yet.

“God has given you one face, and you make yourself another,” he said at last, so softly that I wasn’t sure I’d actually heard him. When I glanced back, he was spinning the skull in a slow circle in his lap.

I put a little more space between us.

Hamlet stiffened suddenly. “

Shh.

Listen.”

“I don’t hear anything.”

He lifted the skull on one palm. Its features glinted in the semidarkness. “Do you know him?”

The skull’s empty eye sockets stared back at me. The crest of its forehead was ridged and uneven, one large crack spidering over the bumps of bone. Its grinning teeth were slightly crooked, some edges worn flat, others tilted inward. Too much detail for a prop.

I swallowed hard. “No. I don’t know him.” The twinge in my neck crept up into my own skull, opening like the petals of a flower. I could feel it pulse behind my right eye.

“He wants to speak to you.” Hamlet’s face was serious. Almost tender. Like he was lifting a puppy or a full bowl of soup, he tilted the skull’s gritted smile to my ear.

I forced myself not to jerk away.

“I don’t hear anything,” I said again, after a second. “Are you going to make it talk, like some creepy puppet?”

“Listen,”

Hamlet hissed. The skull’s teeth brushed my earlobe. “He says, ‘Remember me.’”

The pulse behind my eye thumped harder. “‘Remember me’? What am I supposed to remember about Yorick?”

“Not Yorick.” Hamlet frowned like this was obvious. “Your father.”

My whole body went cold. I whirled toward him, making my voice stiff and clear as an icicle.

Katharine Hepburn.

Maggie Smith.

“Don’t talk to me anymore.”

Hamlet leaned toward me again, his cracked-ice eyes wide. “I think I saw him yesternight.”

“Stop it.” I tried to stand up, but my body was fastened to the chair.

He pointed to the stage. “Look where it comes again!”

From behind the curtain, there came the hollow sound of footsteps.

The ache in my head froze. My heart shot up into my throat and stuck there.

The dusty velvet curtains twitched.

Another strangled heartbeat. Then the curtains parted, and a man stepped out onto the lip of the stage.

The dimness smudged his edges, and the spotlight gave him a blurry glow, but I’d seen enough portraits on scripts and books and classroom walls to recognize him. The

Renaissance-Elvis pompadour. The heavy-lidded eyes. The gold hoop earring.

In person, Shakespeare looked younger. Sharper. Every motion he made was pared down to fine lines, so he seemed to move with perfect precision, not a flicker of energy wasted.

His eyes were very dark. They speared through the spotlight, straight down into mine.

“Be as thou wast wont to be,” he said, in a quiet, resonant voice. “See as thou wast wont to see.”

“Jaye . . .” said another voice. “Jaye?”

The auditorium collapsed.

The armrests sagged under my elbows. The prickly upholstery flattened into cotton sheets. The ache in my head thawed, pounding back to life.

“Jaye? Are you still awake?”

A face floated above me. I blinked up at it, fighting against the flood of ugly yellow light, while the white ceiling and white walls and white floors rebuilt themselves, and the floating face crystalized into my sister.

Sadie looked a little like me, with all the good parts amplified and the bad parts erased. Her jaw was firm. Her nose was straight. She had a runner’s long, slim body. Her hair was sleek and wavy and shimmery red-brown. I suppose at least my hair might have looked like hers, if I wasn’t always dyeing it. But I needed the things that made me different from Sadie. Comparisons were a bad idea.

Sadie sat on the edge of the bed, wearing a thin green sweater and one of her million scarves. Its fringe brushed my arm as she leaned over me. “Are you okay?”

I didn’t know what expression to put on. I recognized the room, in a hazy way. And Sadie had said “are you

still

awake.” Terrified confusion didn’t seem appropriate. I struggled for a blank face.

“My head hurts.” My voice came out deep and raspy, like I’d been gargling with gravel.

“I know it hurts.” Sadie leaned back again. “You’ve said so about eight thousand times.”

“My cheek hurts too,” I said, in my new, raspy voice. “Have I said

that

eight thousand times?”

“Seven thousand.” Sadie’s eyes narrowed slightly, and I knew she was doing that thing where she tries to pry beneath my outer layers, to see past what I’m showing her and peel me down to the truth. “Do you remember where you are?”

“. . . The hospital.”

Sadie waited. So did I.

As usual, she cracked first. “And what are you

doing

in the hospital?”

I traveled backward through the fragments. The auditorium, Hamlet, the cracked skull. A sparkling white field. Snow. A deep voice. Someone gently lifting my hand.

“I was . . .” I mumbled. “It’s just—flashes.”

Sadie gave a muted sigh. “We were skiing,” she prompted.

“Skiing?” I blinked twice, but this time, the room didn’t change. “You mean—you and Mom and

me?

”

“I know. Jaye Stuart participating in a sport?” Sadie shook her head. “Blue moons colliding. Snowballs piling up in hell.”

It must have been the grogginess filling my body, because I almost broke the rule. “But we haven’t gone skiing since—”

“I know.” Sadie cut me off just in time. “Mom and I just thought it would be nice. Good memories. You know.”

I had to fight to keep the disbelief off my face.

Good memories? Mom and Sadie shushing happily off on their skis. Me wobbling, stiff and terrified, on the learner’s slope, whining about the cold, my sore ankles, the steepness of the hills. Dad’s teasing smile turning embarrassed. Then tight. Then angry. I remembered one trip—I must have been eight or nine—when he grabbed me by the arm and shoved me down the incline while I screamed and cried and strangers stared at us. At the bottom of the bunny hill, Dad leaned close and hissed at me through clenched teeth,

“You’re not even trying,”

before gliding away, leaving me alone. I’d spent the rest of that trip—and every ski trip afterward—waddling up and down the grounds near the lodge, trying to look like I had just finished a great run, or like I was just about to head out on another, practicing my lies for Dad.

I did the learner’s slope four times,

I’d say, hoping my frostbitten cheeks would be enough evidence.

I tried. Really.

“I hated those trips,” I told Sadie.

“Well, there may have been bribery involved, but you’ll have to ask Mom about that.”