Dreaming in Chinese (17 page)

Read Dreaming in Chinese Online

Authors: Deborah Fallows

Tags: #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Translating & Interpreting, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Once home, I looked up

xìngfú

in my dictionary, which elaborated on the standard definition of “fortunate.”

Xìngfú

, it said, is “used in a sublime sense, denoting a profound and almost perfect happiness.”

That was a poignant moment for me. Sasha, a working girl from the coal provinces of the middle of China, had plucked out a perfect word to describe our homegoing to our family and friends.

I try now to appreciate the compound words, in English as well as in Chinese. I try to not let them become so commonplace that I don’t really hear what lies behind them.

18

In this case, Chinese had borrowed a lot of

diàn

words from

Japanese. Japan modernized earlier, and they created new compound words for technological terms and Western ideas based on their own characters, some of which Chinese later adopted.

19

The fourth tone on

nào

is lost when it becomes part of the compound word

rènao

.

Tīng bù dǒng.

I don’t understand.

10.

A billion people; countless dialects

M

Y WORST EXPERIENCE

with a Mandarin teacher in China was with a guy I’ll call Eddie. I studied with about a dozen different tutors and teachers during our time in China and found there were two types, whom you can think of as professional and amateur. The pros, college-trained teachers of Chinese as a foreign language, all seemed cut from the same cloth. They were enthusiastic, practiced and patient. They really knew their stuff technically: the grammar, the drills, the rhythms of a class. The amateurs, mainly freelance tutors, were more of a mixed bag of eccentric personalities and styles. It took a certain chemistry and meeting of minds between tutor and student for the interaction to work well. When the chemistry was right, the results could be great. I learned my most useful and practical “street language” from some of my amateur tutors.

Eddie was an amateur. I found him on Craigslist, which offers plenty of tutors to choose from. Eddie’s résumé showed that he had an unusual background, one in classics and linguistics, so I was intrigued. Unfortunately, there turned out to be a gap between the Craigslist Eddie and the real-life Eddie. (Surprise surprise!)

Real Eddie was rather puffed up about his scholarly background and dead set that I should learn exactly what he wanted to teach me. For my own good, he said, I needed to learn to talk about antiquities and Confucius. I told him that actually, it would be a lot more valuable to me to learn grammar and language for everyday life.

Ignoring me, Eddie pushed on: “How old is China?” he demanded. “China is five thousand years old,” I answered, parroting part of an oft-heard catechism. Then he asked me the Chinese names for some other ancient countries besides China. I happened to know India (Yìndù), but stalled on Greece. “

Xīlà,

” he said. (I should have known that one.) “How about Egypt?” he asked. Who would know this, I wondered. (It is

Aijí.

)

Eddie was starting to seem like a bully. “Mesopotamia?” he asked. I told Eddie flat-out that I didn’t want to learn how to say Mesopotamia in Chinese, because I would never remember it, and I didn’t want to know how to say Sumeria either, because I would never have occasion to use it. He was not pleased. We both recognized a deadlock, and Eddie looked relieved when I said I would “get back to him” about the next lesson.

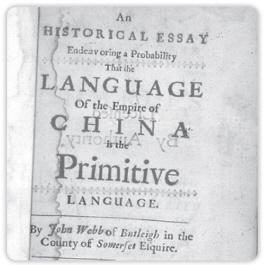

It was a pity, because I think Eddie would have had a lot to teach me about the history of Chinese. It was clear that he, like many Chinese people, loved much about his country—its ancient history, its deep culture and the stories of its linguistic evolution. Eddie would probably love the account I stumbled across about John Webb, a seventeenth-century English architect and amateur scholar. Webb wrote about Stonehenge, and he also dipped his toe somewhat sloppily into the history of Chinese language. Webb argued that Chinese was the language of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the original language before the Tower of Babel, a hypothesis quite readily dismissed by others.

He produced a now quaint-seeming book on the subject (

see below

). I am sure that Eddie would have made good use of it.

A more accurate history of recent developments in the Chinese language would report that it took a sweeping turn in 1912, at the end of the imperial era and the founding of the Republic of China. It was apparent to the idealistic new leaders that the current language situation was dysfunctional as a backbone for a young, unified nation. They needed a change.

At that time, imperial court officials spoke a version of the Beijing dialect for governmental purposes, leaving masses of ordinary people and daily life across the vast reaches of the rest of the country awash in a soup of mutually unintelligible disparate languages and dialects. Only a thin slice of the highly educated elite mastered the written-only language, called Wenyan, or as we know it, classical or literary Chinese, a language of thousands of characters that largely lacked tenses, gender, grammar, and even prepositions, and that

no one actually ever spoke

. This was an extreme version of the Catholic Church’s situation before the reforms of the 1960s, in which Latin was the official language, one that no parishioners actually spoke; the difference was that many ordinary Catholics at least understood the Latin Mass. China’s situation effectively cut off the ordinary people from high literary culture. But as China engaged with the outside world, intellectuals began to recognize that to pull their new country into the modern era, they needed to address both language issues: the spoken languages that varied so dramatically from region to region, and the written language that was inaccessible to all but a tiny elite. What followed was about four decades of confusing and emotional language debates, the linguistic element of the mass effort that began to pay off in unifying the country.

The question for the spoken language was: should China formally establish a single national language? On one side of the principled argument were those who said a national language would unify the country and help move it forward as a strong, more integrated modern republic. They were largely Beijingers, who knew that they had some advantages on their side: their northern dialect was more widely spoken than any other dialect, and since Beijing was the main cultural and intellectual center, a variant of the Beijing dialect was the most logical candidate for such a “national language.”

On the other side were those who said that choosing any one language was unfair; it would marginalize everyone who was not a native speaker of that language. Arguing this side were, for example, the Shanghainese, who feared the one-language solution (probably a derivative of Beijing Mandarin) could snuff out their own regional culture. The rivalry between Beijingers (

Běijīngrén

) and Shanghainese (

Shànghǎirén

) has long been both personal and bitter.

Then as now, Shanghai had bling, sophistication, commerce. Beijing had cultural power, history, the academy. Today, almost a century beyond the official language debates, I regularly hear the question “Shanghai or Beijing, which do you like better?” It is a dreaded query, one that brings trouble no matter which way you answer it. Here is a typical scene of how the exchange plays out.

One nice Beijing morning, I went looking at apartments. I dreamed of moving from our sterile if convenient digs, and I called an agent who was showing an apartment in a funky old diplomatic compound. (Luckily for us, foreigners can now live just about anywhere they want to in China, a dramatic change from being restricted to a few designated housing compounds through the mid-1990s.) The agent was one tough young city woman. We got around to chatting about my having lived recently in Shanghai. In the middle of our conversation, she blurted out, “I hate Shanghai people!” I was taken aback and asked her why. “I don’t know. I just hate them. I hate them all.” I asked her then about Shanghai people: “Do they hate Beijing people?” “They hate everyone,” she answered. Conversations like this were not rare.

Squabbling over the choice of a national language lasted a few decades. Interestingly, the Nationalists, who were in power first and later fled for Taiwan, and then the Communists, who followed them into power, both reached a consensus that a derivative of northern Mandarin spoken around Beijing (but which toned down some of the more identifiable markers of Beijing-speak, like the classic pirate-sounding “arrr” endings) would be the official language. The Nationalists called this

Guóyǔ

, “the national language.” The Communists called it

Pǔtōnghuà

, “the common speech.”

The debates and decisions about the written language were even more fundamental and consequential. In the exciting, infectious spirit of the new republican and post–May Fourth Movement era of the early 1920s, when the Chinese began to reexamine almost every aspect of their traditional culture, writers like the still-revered Lu Xun (who was by tradition a writer in classical Chinese but who switched his allegiance to the idea of a written language for the common people) were creative, daring and prolific. The new written language (often referred to as the “vernacular” in this context), was a much better match, grammatically and otherwise, with the way people actually spoke. It was called

Báihuà

, literally, “white language” or “plain language,” and it made literature newly accessible to ordinary people. Mass-circulation magazines and newspapers were also born during this time, which gave many more ordinary people so much more to read besides what they had been used to—mostly just official notices and street signs!

There was another problem, however, because the Chinese character system, which was suited to ancient, unspoken literary Chinese, was a cumbersome match with the very different vernacular in which the new literature was being written—the language of everyday life.

As a solution, some writers and reformers began to believe that it was time for China to make the switch to a Western-style alphabet, or some other phonetic writing system. (Korea’s

hangul

and Japan’s

hiragana

and

katakana

, for instance, have no relation to Western alphabets but are logical and phonetic and fairly easy to learn.) Reformers pointed out various advantages of adopting a phonetic writing system. A phonetic alphabet, with agreed-on pronunciations for each letter or symbol, could help codify an “official” pronunciation of a new nationwide official language and could help kids learn “correct” pronunciation. Also, it could help more people learn to read and write more easily. (As it happened, the idea of official nationwide pronunciation was eventually abandoned, in the face of powerful, deep-rooted regional accents. Even in his day, Chairman Mao spoke with such a heavy Hunan accent that most of the Chinese masses he ruled simply couldn’t understand him when he talked. It would be like forcing people from Mississippi to talk as if they were from Boston, or Liverpudlians to talk as if they were from London. Look how much trouble Henry Higgins had teaching one sharp little girl!)