Dublin Folktales (3 page)

Authors: Brendan Nolan

Boxing bouts had no time limits at the time, so that two men fought to exhaustion or victory before cheering onlookers. Donnelly's most famous victory was against George Cooper, the heavy-weight champion of Britain, whom he beat on the Curragh of Kildare. But fame is fleeting. It is said that drinking copious amounts of cold water after a later fight killed Donnelly in the end. By then, he had failed as a pub owner several times and was broke once more.

Thousands of people turned out for his funeral and internment at Bully's Acre. The cemetery was claimed, rightly or wrongly, to contain the grave of Brian Boru, the High King of Ireland. Donnelly was no sooner buried than his body was stolen by the Sack-'em-Ups and sold to a Dublin surgeon named Hall. But Hall was not to be in possession of the body of the people's champion for long.

It was soon established which surgeon had paid cash on delivery for the body of Dan Donnelly, the people's champion. Tense discussions took place between Donnelly's followers and Hall over the body. Accepting that the remains must be returned, Hall negotiated the removal of the right arm from the body and the attached shoulder blade in order to study the muscle structure. When this was agreed, the body was re-buried in the Kilmainham graveyard with due reverence, where it lay undisturbed from then on.

Donnelly's right arm was to do more travelling than the rest of his body ever did. It was displayed in a pub for many years in the town of Kilcullen, County Kildare, not far from the scene of its most famous fight. After that, it travelled the world to appear in various exhibitions of Irish interest.

The cemetery, where its companion arm and the rest of Donnelly's body fell into decay is no longer in use and there are no Sack-'em-Ups in operation any more.

Another story told about the robbers relates how a Peter Harkan, a well-known Dublin surgeon and teacher of anatomy, died in Bully's Acre in the early 1800s while on

a corpse-stealing exhibition. He was spotted in the cemetery by a party of watchmen who chased him and his assistants. The assistants crossed the perimeter wall in time but Harkan was caught by the legs by the watchmen. Harkan's pupils pulled his upper body to free him but such was the counter force used by both parties that the grave robber Harkan died in the graveyard that he had come to rob.

Some say it was a fitting end for him, others argue that Harkan and the resurrectionists performed a public duty in expanding the knowledge of the human body. It would have been nice, however, if they had asked permission of the bereaved before digging people's bodies up again and spiriting them into the Dublin night while they were freshly dead and not yet at their eternal rest.

When you die that should be the end of it. Otherwise, what's the point of death?

B

LOOD

F

IELD

Ghost stories were told aplenty in olden times in Ireland. They were told with such conviction that people believed them. Many things that seem in darkness to be real, may in daylight seem more a fancy of the night. Nonetheless, people paid attention when the storyteller told the tale, for who knew what might befall them on the dark roads when night fell?

Reports of ghostly appearances and hauntings died away when rural Ireland was electrified in the twentieth century under a scheme that brought connection to the national grid for most houses, however remote and inaccessible. Dancing candle and shadows thrown by paraffin lamp gave way to a steadier light.

The wandering spirits also began to disappear to the detriment of ghostly storytelling, but to the greater peace of local inhabitants. Reports of strange shapes and appearances in darkened rooms fell away. However, a working clairvoyant relates a twenty-first-century story concerning a house in County Dublin in which Michael, a six-year-old boy, lived with his parents and family.

A frightened Michael told his parents that he was seeing visions at night of soldiers from an army of long ago, moving towards and away from a battle. They were passing along the road outside their home. Some of the warriors had

even passed through their semi-detached home, he said. His parents rationalised the stories as the imaginings of a child. While not entirely dismissing the boy’s stories, they were content when he went asleep each night, for his dreams were waking dreams and all the more unsettling for that. While he slept, silence settled on the upper floors of the small home on a modern estate in the suburb of Clondalkin in the west of the city.

However, the clairvoyant was called in by Michael’s father when he, the father, encountered an armed soldier on the stairs of the house, giving credence to the boy’s story and frightening the adult man as much as it terrified the child. The soldier passed by without a word and seemed to pass out of the building without touching the closed, locked and secured door. The father then fervently agreed with his son that there was indeed something stirring in their home.

The clairvoyant came to the house and did what she could for the dark curly-haired boy and his family so that calm could be returned. She sat with the boy and talked about what they could both see. She helped him draw in his special dreams until they were finally closed off to the boy’s vision.

Before the window closed down, the clairvoyant gazed at the visions with Michael and through him they saw an encampment of a time from long ago, on the streets and roads where the new houses now stood. There were tents and weapons stacked together and defences raised around the encampment against sudden attack by the opposing army.

In the distance, at night, there were red and yellow bonfires blazing in the sky. Flickering shadows of men passed before and behind the fire. At other times, women could be seen on a battlefield seeking fallen family members and administering to the wounded and the dying. Armed soldiers with long, matted hair tucked into their belts, clad in

makeshift body armour and armed with shields and swords and long two-handed battle-axes passed by the boy’s home in the middle of a housing estate, without a word.

A man clad in sackcloth lingered nearby, on another day, waiting for someone to come by, amidst the crying of grown men and the rolling sounds of mortal conflict from a battlefield not far away. Bodies of the shocked dead and terrified wounded were piled high and moved back on creaking two-wheeled carts, drawn by weary oxen away from the battle. The dead were tumbled to one side where they lay; the wounded were tended with rudimentary care and dressings. Some of these returned to battle, some withered and passed away in their own time.

There was nothing the watchers could do except gaze at the drama unfolding before them. In time, the images dimmed and vanished from the ken of the little family. When all was quiet once more, the clairvoyant moved on.

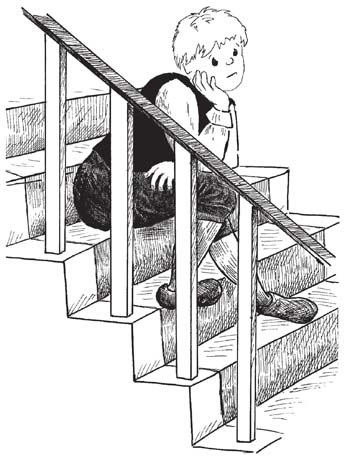

At the same time in another house in the same area, a young mother had an unexpected guest each night when she told bedtime stories to her two young children. A small boy came down the stairs from an attic room and sat upon the steps staring through the banisters until the stories were told once more. He was dressed in clothes of another time. He never spoke, but walked quietly to the top of the house when the story ended. When

the adults went to search for him, he was nowhere to be found, no matter how hard they looked. Yet each night there he was again waiting for a story to be told.

In time, he stopped appearing.

In the same area, many years earlier, Aisling, now a grown woman, lived as a young girl, before acres of modern houses were planted in the verdant fields. She had wandered free across rolling meadows in the summer of her childhood. That is, except for one field which she avoided, for the strong smell that came from it repulsed her senses when she approached the enclosure. Though she was too young to recognise the smell’s origin as blood, in her childish way Aisling called it the ‘Weirdie Field’. She saw with young eyes that the grass was a deeper green and lusher than the surrounding fields. She felt there was a restless silence about the place and she did not like it. Aisling continued to play in the other fields and didn’t let the ‘Weirdie Field’ bother her.

As an adult, living elsewhere in Dublin, and with the fields of her childhood now covered in housing estate after housing estate, with housing stock rolling across hill and plain alike, and the city approaching ever closer, she researched the lore of her home place to satisfy an adult curiosity. She discovered the name of the field to be the ‘Blood Field’, in the old tongue. It was named so in a time when names were descriptions of places and the events that occurred there. It was where a battle had taken place, more than a thousand years ago, and where it seemed ghosts of the fallen lingered on awaiting some resolution.

A Viking settlement once stood many fields away from Aisling’s childhood home, she discovered. It was ruled over by Olaf the White, a Viking chieftain who was named King of Dublin by the Vikings. The settlement was in the townland of Dunawley (Olaf’s Fort) in the general area of Clondalkin. Not content with Irish tribute and subjugation, Olaf and his men sailed down the nearby Liffey in their warships and

across the Irish Sea in a great fleet of fighting men to raid in Northumbria, in or around

AD

850. While he was away, Gaithine, an Irish chieftain, raided the Viking settlement to wrest control from the Viking garrison. Much blood was shed in the battle for supremacy between the opposing forces.

It was to be a further sixteen years before Olaf returned to Dublin, laden with booty from his warring escapades. He and his belligerent warriors came with great determination to tackle the Irish fighters. Further killing and mayhem ensued across the open fields in the highlands above the valley of the River Liffey, before the warring was done. Thousands of souls perished through those years of attrition and retribution. We know not what matters may lie unfinished among the souls of the dead.

One-on-one combats were fought to finality in the midst of huge battles where thousands of desperate men killed their foes. When it was over, the bodies of the fallen were covered over where they lay. The soil was enriched by their spilt blood and their crushed bones. In time, rotting carcasses produced bone meal that fertilised the blood field where green grass grew high above where they lay, forever stilled.

Aisling moved away to her new married home. Her childhood home is no more; it was sacrificed for a new road from Dublin to the west, many years ago now. Michael’s modern house has been set to rest; no more visions intrude on his life. His father has seen nothing since the clairvoyant left and his mother does not speak about it at all. But there is a sense of unfinished business in the air. A sense of watchers watching. For what we know not.

In modern times, a local businessman met an associate in an overspill shopping-centre car park, to hand over some documents relating to some business they had together. On a warm July day in West Dublin they shook hands and parted. But as the businessman turned to step back into his car, a breeze ran across the otherwise empty car park and he shivered. Someone had stepped on his grave.

He looked across to where some very old trees grew in the distance. He fancied he saw some flitting dark shadows moving beneath the trees, but when he blinked and looked again, he could see nothing. All was still. Heat returned to his head and he turned back to his car to leave as expeditiously as possible. That car park is built close to the old Blood Field. It was daylight. Shadows of firelight were not at play. That businessman said he will not return there.

Unless he must … For who knows what lies beneath or beside the Blood Field of Dublin? Some matter lies unfinished there. There are some shadows that not even the brightest of lights can dispel and some stories of which we know nothing.

T

WO

M

AMMIES

AND A

P

OPE

It’s a traumatic time for anyone when a mother is lost. Tom lost his mother among a million people in Phoenix Park, and his mother-in-law somewhere on a Dublin beach in high summer.

Tom’s mother-in-law had invited all her adult children and their lovers and spouses to go to Portmarnock Beach on a sunny Sunday afternoon. However, she caught a bus to Dollymount Strand instead, because she had been to Portmarnock too many times before. Her family spent the day walking the sands looking for her. They tramped in and out of the dunes, had rows, said they were sorry, had a quick hug in this time of need, and walked on again. They stared out to sea with their hands to their eyes in case she had been kidnapped by pirates or had swum out to a shipwreck and found a new life there with survivors on Ireland’s Eye beside Dublin Bay.