Early Dynastic Egypt (15 page)

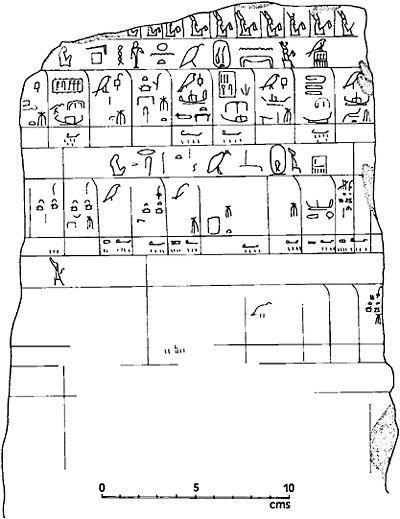

Figure 3.2

Royal annals. The Cairo fragment (new collation from the original).

THE FIRST DYNASTY

Ironically, it is the First Dynasty, the remotest sequence of kings in the Early Dynastic period, that is the best understood, in terms of the number of rulers and the order of their succession. The Abydos king list and Manetho agree in recording eight kings for the First Dynasty, and this number is confirmed by the recently discovered necropolis sealing of Qaa. Indeed, this sealing provides the best contemporary evidence for the historical

accuracy of Manetho’s First Dynasty. The original identification of Merneith as a king, rather than a queen regent (Petrie 1900:5, chart opposite p. 1), caused some confusion, leading to Narmer’s exclusion from the dynasty and a focus on Aha as the first king. There is no doubt that Aha’s reign was marked by important innovations; none the less, first place in the sequence of eight kings properly belongs to Narmer (Lauer 1966:169– 70; Shaw and Nicholson 1995:18 and 89; contra Baines 1995:131), and the Den and Qaa necropolis sealings confirm that this was the belief of subsequent generations of Egyptians as well. The difficulties in correlating the names recorded in later king lists (usually the

nbty

names) with those attested on the monuments (usually the Horus names) have confused what should be a relatively straightforward picture. The debate about the true identity of Menes—first king of the First Dynasty according to the Abydos list and Manetho—has also muddied the waters (Emery 1961:32–7). Those scholars who identify Menes with Aha posit the existence of an ephemeral King Athothis between Aha and Djer (Dreyer 1987:39) in order to make up the required eight rulers for the dynasty as a whole, although no such ruler is attested on contemporary monuments or inscriptions. (The possible royal tomb at Abydos comprising the pit B40 with or without the adjacent tomb B50 has been attributed to ‘Athothis’ on the basis of its location and design [Dreyer 1990:67–71], although there are no inscriptions to support this view, and the necropolis sealing of Qaa would seem to argue against the existence of an extra king between Aha and Djer.) Despite such difficulties, something of a consensus has been reached about the composition of the First Dynasty, greatly assisted by new discoveries, especially in the royal cemetery at Abydos. The duration of the First Dynasty cannot be estimated with any precision, since accurate historical records are, for the most part, absent from this early period. Estimates depend to a large extent on hypothetical reconstructions of the Palermo Stone and its associated fragments, together with a notional figure of twenty-five to thirty years for a generation. Various scholars have proposed figures ranging from two hundred to two-hundred-and-forty years for the eight kings of the First Dynasty (Lauer 1966:184, especially n. 5), but such guesses are unlikely to be improved upon without new, more precise, historical evidence.

Narmer

Some time around 3000 BC the king whom we know as Narmer acceded to the throne of Egypt. The contemporary writings of his name—usually abbreviated to a single sign, the catfish (which had the phonetic value

n r

in later periods)—make it rather unlikely that his name was read as ‘Narmer’; however, this name is universally used and will no doubt remain so until an acceptable alternative reading is proposed. According to Manetho, the First and Second Dynasty kings originated from Thinis (or This), the capital of the Abydos region, thought to lie near—or indeed under—the modern town of Girga. The presence of First and late Second Dynasty royal tombs at Abydos seems to confirm Manetho’s account, since Abydos was the principal necropolis of the Thinite region. Whether or not Narmer had a royal residence at This, he clearly felt strong enough ties to the region and to his Predynastic forebears to maintain the tradition of being buried in the ancient ancestral necropolis. If Narmer is to be associated with the historical and/or legendary figure of Menes (Lloyd 1988:10), he may have been the first King of Egypt to reside at Memphis. Herodotus recounts how Menes diverted the course of the Nile to

found his new capital. However, it is noteworthy that, to date, no monument of Narmer has been found at Saqqara, the élite necropolis serving Memphis.

One of the most heated and protracted debates in Egyptology has raged over the identification of Menes: Narmer, Aha, a conflation of the two, or a mythical figure representing several rulers involved in the process of state formation? Dependent upon this argument is also the proper placement of Narmer: at the end of so-called ‘Dynasty 0’ or at the beginning of the First Dynasty? Although there is perhaps stronger evidence for the latter view (and for the identification of Menes as Narmer), the entire debate is actually rather anachronistic, since the dynasties were not invented until some two-and-a- half-thousand years after Narmer’s lifetime. Nor did the Egyptians have the same sense of history as ourselves. What is of significance is the position held by Narmer in the eyes of his immediate successors, the kings of the First Dynasty. For at least two of them, Den and Qaa, Narmer seems to have been regarded as a founder figure, at least in the context of the royal burial ground at Abydos. In this context, it may also be significant that the earliest inscribed stone vessel from the hoard of thousands buried under the Step Pyramid at Saqqara dates from the reign of Narmer (Lacau and Lauer 1959:9, pl. 1 no. 1). It has been suggested that the inscribed ‘heirlooms’ collected together by Netjerikhet to furnish his burial may have represented an attempt to harness the authority and legitimacy of the king’s predecessors (F.D.Friedman 1995:10).

It is tempting to interpret the significance of Narmer’s reign in the light of his most famous monument, the ceremonial palette from the ‘Main Deposit’ at Hierakonpolis (Quibell 1898a: pls XII-XIII, 1900: pl. XXIX; Petrie 1953: pls J-K; Kemp 1989:42, fig. 12). The scenes carved on this object are probably the best-known and most intensively studied from early Egypt. Whilst the symbolism of the scenes is clear—they convey Narmer’s triumph and dominion over both Upper and Lower Egypt, particularly the latter—the occasion for which they were carved will never be known. A straightforward historical interpretation of the monument is now generally considered to be unsophisticated and old-fashioned. Instead, it is argued, the palette may commemorate the ritual re-enactment of an earlier military victory (the ‘Unification of the Two Lands’ was an integral component of early coronation rituals), or may belong entirely within the realm of myth and symbol, conveying the omnipotence of the king without alluding to any specific historical incident. However, a partially preserved year label of Narmer, found during the recent German excavations on the Umm el-Qaab, may offer support for the older, historical interpretation of the Narmer palette. The label apparently records the same event as the palette: it shows the catfish of the king’s name smiting a bearded captive, identified by the papyrus plant on his head as an inhabitant (and leader?) of Lower Egypt.

Another important monument of Narmer’s reign is the decorated macehead, also from the Hierakonpolis ‘Main Deposit’. Like the palette, themacehead has been variously interpreted. An earlier generation of scholars believed it to commemorate Narmer’s wedding to a northern princess. However, the (female?) figure in a carrying-chair shown before the enthroned king may represent a deity, and given the likely southern origin of Queen Neith-hotep there is no corroborative evidence that Narmer sealed the political unification of Egypt by marrying a northern heiress. None the less, a Lower Egyptian setting for whatever ceremony is depicted seems to be confirmed by the depiction of a shrine with a pitched roof, surmounted by a heron: this was the shrine of Djebaut, a

district of Buto in the north-western Delta. A complicating factor is the wavy-walled enclosure shown beneath this shrine, which has been compared with the ceremonial centre recently excavated at Hierakonpolis (R.Friedman 1996:33).

Compared to his known predecessors, Narmer is much more widely attested in archaeological contexts. His name has been found on sherds as far afield as Tel Erani (Ward 1969:216, fig. 2), Tell Arad (Amiran 1974,1976) and Nahal Tillah in Israel’s northern Negev (Levy

et al.

1995). Similar sherds have been excavated in the north- eastern Nile Delta (for example, van den Brink 1992b: 52, fig. 8.3; in preparation), suggesting active trade between Egypt and southern Palestine in Narmer’s reign. It has been suggested that the Narmer Palette records a military campaign against Palestine (Yadin 1955; Weill 1961:20), although this interpretation is disputed (Ward 1969). More convincing evidence for direct contact between Egyptians and

Asiatic

s during the reign of Narmer is provided by a fragment of inscribed ivory from Narmer’s tomb (B17) at Abydos. It shows a bearded man of Asiatic appearance in a stooping posture, perhaps paying homage to the Egyptian king (Petrie 1901: pl. IV.4–5). In the Delta, a complete vessel bearing Narmer’s

serekh

was found in a grave at Minshat Abu Omar (Kroeper 1988: fig. 141) and a sherd incised with a damaged

serekh

which may be the name of Narmer was excavated at Buto (von der Way 1989:293, fig. 11.7). Further objects bearing the name of Narmer have come to light at Zawiyet el-Aryan (Kaplony 1963,1:65–6; II: nn. 252–3, 255; III: pl. 120, no. 721; Dunham 1978:26, pl. XVIa), Tura

(Junker 1912:47, fig. 57.3–4; Fischer 1963:46, fig. 3c-d, 47) and Helwan (Saad 1947:165, fig. 13a) in the Memphite region; Tarkhan, near the entrance to the Fayum (Petrie

et al.

1913: pl. LXI; Petrie 1914: pls VI, XX.l, XXXVIII; Fischer 1963:44 and 45, fig. 2;

Kaplony 1964: figs 1061–2); and Abydos (Petrie 1900:5, pl. IV.2; 1901: pls II.3, 4, 6, 7,

X.I, XIII.91–3, LII.359), Naqada (Spencer 1980:64, pls 47, 52 [Cat. 454]) and

Hierakonpolis (Quibell 1900: pl. XV.7=Kaplony 1963, III: pl. 5, fig. 5; Garstang 1907: pl. III.l=B. Adams 1995:123–4) in Upper Egypt. Finally, there is a rock-cut inscription comprising the

serekh

of Narmer and a second, empty

serekh

at Site 18 in the Wadi Qash, half-way between the Nile valley and the Red Sea coast in the eastern desert (Winkler 1938: 10, pl. XI.l). Activity in Egypt’s desert border regions is attested from Predynastic times, and the attractions of the eastern desert (principally its stone and mineral resources) clearly encouraged state-sponsored expeditions from the beginning of the First Dynasty.

Aha

There is little doubt that Narmer was succeeded by a king whose name is rendered as Hor-Aha, or more simply as Aha (‘the fighter’). One of the most impressive monuments from the early First Dynasty was the royal tomb at Naqada (de Morgan 1897), now sadly lost through erosion. Identified originally as the tomb of Menes, it is now generally acknowledged to have been the burial place of a senior female member of the First Dynasty royal family named Neith-hotep (see de Morgan 1897:167, figs 550–5; Spencer 1980:63, pls 46 and 51 [Cats. 449, 450]; 1993:61, fig. 41). The occurrence of several labels and sealings of Aha in the tomb probably indicates that the occupant died during the king’s lifetime, and that he oversaw the burial. In this case, Neith-hotep is most plausibly identified as the mother of Aha. The location chosen for her tomb may indicate

her provincial origins. Naqada is known to have been a major centre of political and economic influence in the Predynastic period, and it is not unlikely that Narmer—a member of the Thinite royal family – would have taken as his wife a member (perhaps the heiress?) of the ancient Naqada ruling family, to cement an important political alliance between two of the key centres of Upper Egyptian authority.

Aha seems to have made a decisive choice in favour of Memphis as the principal centre of government: the earliest élite mastaba tomb on the escarpment at North Saqqara—overlooking the site of ancient Memphis—dates to his reign (Emery 1939), and belonged to a senior figure in the national administration, perhaps a brother or other male relative of the king’s. Aha himself maintained the tradition of his forebears, and was buried in the ancestral necropolis at Abydos (Petrie 1901). One of the accompanying

subsidiary burial

s yielded objects bearing the name Benerib (Petrie 1901: pls III.l, IIIA.13; Spencer 1993:79, fig. 57)—literally ‘sweet of heart’—and this may have been the name of Aha’s wife. The design of the king’s mortuary complex shows important new features; taken together with the Naqada and North Saqqara tombs, it marks out Aha’s reign as a period of architectural innovation and sophistication. Craftsmanship, too, seems to have flourished under Aha. A few inscribed objects have survived to attest the skills which the king could command: two copper axe-heads; a fragment of an ivory box bearing the king’s name and that of Benerib (Emery 1961:53, fig. 13; Spencer 1993:79, fig. 57); a fragment of a large vessel of

glazed composition

(faience), with the king’s

serekh

inlaid in a darker glaze (Petrie 1903:23, pls IV, V.32; Spencer 1993: 73); and two immaculately inscribed white marbles (Kaplony 1965:6 and 7, fig. 4).

Other books

This One is Deadly by Daniel J. Kirk

A Cry for Self-Help (A Kate Jasper Mystery) by Girdner, Jaqueline

Punto crítico by Michael Crichton

Wild Card: Boys of Fall by Mari Carr

Dawn of the Mad by Huckabay, Brandon

Critical Care by Calvert, Candace

Lauren Barnholdt - At The Party 04 - KissingPerfect by Barnholdt, Lauren

Dark Legacy by Anna Destefano

The Elegant Gathering of White Snows by Kris Radish

Wild Iris Ridge (Hope's Crossing) by RaeAnne Thayne