Early Dynastic Egypt (19 page)

region. This may be significant: apart from stone vessels reused for the burials of Peribsen and Khasekhemwy at Abydos (Petrie 1901: pl. VIII.13; and Amélineau 1902: pl. XXI.5, respectively), Ninetjer is not attested outside the Memphite region. It is possible that court activity in the early Second Dynasty was largely, if not entirely, confined to Lower Egypt. This might account for the internal tensions—maybe amounting to civil war – which appear to have engulfed the country towards the end of Ninetjer’s reign. The Palermo Stone hints at possible unrest in Ninetjer’s year 13 (Schäfer 1902:24). The entry reads ‘first feast of

Dw3-Hr-pt.

Attacking the towns of

Sm-r

and

H3’.

The name of the second locality means ‘north land’, and some have interpreted this entry as recording the suppression of a rebellion in Lower Egypt (Emery 1961:93). Although the Palermo Stone breaks off after year 19, two further events which probably belong to the latter part of Ninetjer’s reign are known from stone vessel inscriptions. The ‘fourth occasion of the Sokar festival’ (Lacau and Lauer 1965:88, fig. 172 [no. 273]; Helck 1979:128) probably took place in year 24, judging by the periodic nature of its celebration; the ‘seventeenth occasion of the [biennial] census’ (Lacau and Lauer 1965:89, fig. 173 [no. 274]; Helck 1979:128) will have occurred in year 34.

With so long a reign, it is likely that Ninetjer celebrated at least one Sed-festival. No contemporary inscriptions attest such an occasion, although the statuette of the king discussed below is certainly suggestive. The stock of stone vessels found in the Step Pyramid galleries may originally have been prepared for Ninetjer’s Sed-festival (Helck 1979). According to this theory, the vessels remained in the magazine at Saqqara and were never distributed because internal unrest had already broken out, disrupting communications and weakening the authority of the central administration; the vessels were subsequently appropriated by kings of the late Second and early Third Dynasties. This hypothesis is certainly appealing and has received recent support from Buto (Faltings and Köhler 1996:100 and n. 52): an analysis of the pottery from the Early Dynastic level V indicates a date not later than the reign of Peribsen; the same level also yielded seal-impressions naming ly-en-khnum, one of the most prominent officials mentioned on stone vessels from the Step Pyramid galleries, and placed by Helck in the reign of Ninetjer.

The statuette of the mortuary priest Hetepdief indicates continuity between the first three kings of the Second Dynasty, their mortuary cults being served by one and the same individual. Ninetjer certainly maintained the mortuary cult of one predecessor: an inscribed stone vessel from the Step Pyramid juxtaposes the

serekh

of Ninetjer and the

ka

-chapel of Hetepsekhemwy (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 15 no. 74). Apart from the numerous inscribed stone vessels (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pls 13–16), only two objects bearing the name of Ninetjer have survived. One is a small ivory vessel from the Saqqara region (Kaplony 1964: fig. 1074). The other is of far greater importance in the history of Egyptian art: an alabaster statuette of the king, enthroned and wearing the close-fitting robe associated with the Sed-festival (Simpson 1956). The statuette represents the earliest complete and identifiable example of three-dimensional royal statuary from Egypt.

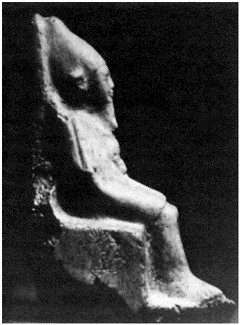

Plate 3.2

King Ninetjer. Crude stone statuette of unknown provenance, now in the Georges Michailides Collection (photograph courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society).

Weneg

As we have seen, there are indications of a breakdown in central authority at the end of Ninetjer’s reign. Before order was re-established towards the end of the Second Dynasty, the kingship seems to have been held by a number of ephemeral rulers who are only poorly attested in contemporary inscriptions (Figure 3.4). Ninetjer’s immediate successor, at least in the north of Egypt, was a king whose

nswt-bỉty

name has been read as Weneg (Grdseloff 1944:288–91). His Horus name remains unknown (cf. Wildung 1969b; Helck 1979:131). An unpublished inscription of Weneg from a mastaba at North Saqqara (S3014: Lacau and Lauer 1959:16, n. 2) is very similar to an inscription of Ninetjer (Lacau and Lauer 1959: no. 68), suggesting that this may be another case of a king re- cutting one of his predecessor’s

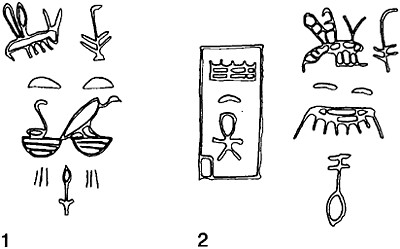

Figure 3.4

Ephemeral rulers, 1: Weneg (1) and Nubnefer (2). Both kings seem to have ruled in the middle of the Second Dynasty. The royal names were incised on stone vessels found in galleries beneath the Step Pyramid of Netjerikhet at Saqqara (after Lacau and Lauer 1959: planches V.4, VI.4).

stone vessels (Helck 1979:124). A second stone vessel from the same Saqqara tomb names the two tutelary goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Wadjet (Kaplony 1965:7, figs 6 and 8, 16 n. 6; Helck 1979:131). However, Weneg is unattested outside Saqqara and there is no evidence to confirm that his rule extended into the south of the country. Twelve stone bowls from the Step Pyramid complex name Weneg (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pls 19 no. 105, 20 nos 101–7). Weneg’s tomb has not been located. If, as is likely, it followed the pattern of earlier Second Dynasty tombs and comprised a set of subterranean galleries, then it may lie beneath the North Court of Netjerikhet’s Step Pyramid complex. Alternatively, there is a possibility that other Second Dynasty royal tombs once stood to the south of the Hetepsekhemwy and Ninetjer galleries; this would explain the location of Sekhemkhet’s step pyramid enclosure some distance to the west. The whole area was levelled by Unas for the construction of his pyramid and causeway.

Sened

According to later king lists, Ninetjer’s second successor was a king with the

nswt-bỉty

name Sened (Helck 1984c). Unfortunately, there are no proven contemporary inscriptions of this ruler. The best piece of evidence is a block, inscribed with the words

nswt-bỉty Snd,

reused in the funerary temple of King Khafra at Giza (Steindorff, in U.Hölscher

1912:106). It may be Second Dynasty, although the epigraphy of the inscription would tend to suggest a slightly later date. An undisputed Fourth Dynasty inscription, in the tomb of Shery, provides the second mention of a King Sened, and indicates that his mortuary cult was celebrated at Saqqara and was still current over one hundred years after his death (Grdseloff 1944:294; Wildung 1969b: pl. III.2; Kaiser 1991). Shery’s titles suggest a connection between the mortuary cults of Sened and Peribsen, a king of the Second Dynasty who is otherwise only attested in Upper Egypt. If Sened ruled only in the north of Egypt and Peribsen only in the south, the juxta-position of their two mortuary cults at Saqqara may indicate that the territorial division of the country which is proposed after the reign of Ninetjer was amicable at first (Helck 1979:132). The only other occurrence of Sened’s name is on the belt of a Late Period bronze statuette of a king (Wildung 1969b: pl. IV.l). This suggests that, however obscure Sened may be to modern Egyptology, he was still remembered by his countrymen centuries after his death. As with Weneg, Sened’s tomb has not been identified. Given the reference to his mortuary cult in the inscription of Shery, it must have been located somewhere in the Saqqara necropolis. It has been suggested, though without firm evidence, that the galleries beneath the Western Massif of the Step Pyramid complex may have been Sened’s tomb, since the tomb of Shery (overseer of the king’s mortuary priests) probably lay a short distance to the north (Dodson 1996:24).

Nubnefer

This name is attested just twice, on stone vessels from the Step Pyramid (Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. VI.3–4 [nos 99–100]). By a network of associations, we may conclude that Ninetjer and Nubnefer were near contemporaries (Helck 1979:124). Nubnefer cannot easily be the

nswt-bỉty

name of Ninetjer, since this name is known (it is also Ninetjer). Nubnefer may, therefore, have been an ephemeral ruler who held the kingship briefly during the period of unrest which seems to have followed the death of Ninetjer. His exact place in the order of succession cannot be established.

Peribsen

Considerable uncertainty likewise surrounds another king from the middle of the Second Dynasty who, uniquely in Egyptian history, chose to replace the Horus-falcon surmounting the

serekh

with the

Seth-animal

. Just why Peribsen chose to break with custom and emphasise the latter god is a mystery. The change may have had ‘real political implications’, perhaps indicating a new development in the ideology of kingship (Hoffman 1980:351). Some scholars have seen a connection between the change of title and two other aspects of Peribsen’s reign: his decision to be buried in the First Dynasty royal cemetery at Abydos, and the fact that he is not attested by contemporary inscriptions outside Upper Egypt. It is possible that Peribsen ruled only in the southern part of the country; he may have been descended from the First Dynasty royal family, hence his decision to be buried at Abydos. Alternatively, if he was an Upper Egyptian usurper, the choice of the Umm el-Qaab as his burial place may have been intended to confer legitimacy, by association in death with the kings of the First Dynasty. The special

features of Peribsen’s reign easily lend themselves to speculative historical reconstructions, but caution should be exercised.

To judge from the tomb inscription of Shery, Peribsen’s mortuary cult seems to have been celebrated at Saqqara despite the fact that his tomb (Petrie 1901: pl. LXI) and funerary enclosure (Ayrton

et al

1904:1–5, pl. VII; Kemp 1966; sealings: Ayrton

et al.

1904: pl. IX.l, 2) are located at Abydos. It is at the latter site that Peribsen is best attested. Some of the sealings from his tomb bear the

epithet

ỉnw S t,

‘tribute (or ‘conqueror’?) of Setjet’ (Petrie 1901: pl. XXII.181). The town determinative after Setjet seems to indicate that the locality lay within Egypt, rather than being the land of Syria-Palestine (also called Setjet by the Egyptians). The town has been plausibly identified as Sethroë in the north-eastern Delta (Grdseloff 1944:295–9), known to have been a cult centre of the god Seth in later times. It is possible, though not provable, that the town was incorporated into the Egyptian realm and a cult of Seth established during the reign of Peribsen. However, this would clearly require Peribsen to have ruled Lower Egypt as well as Upper Egypt.

Two funerary stelae were discovered in front of Peribsen’s Abydos tomb (Fischer 1961:52, fig. 7; BM 35597: Spencer 1980:16, pls 8–9 [Cat. 15]). An official’s sealing from the reign of Peribsen was recently discovered on the island of Elephantine, in the settlement area north of the Satet temple (Dreyer, in Kaiser

et al.

1987:107–8 and 109, fig. 13a, pl. 15a). The inscription names the ‘seal(er) of all the things of Upper Egypt’, and thus indicates the existence of state administrative structures on Elephantine from at least the late Second Dynasty (Pätznick, in Kaiser

et al.

1995:180). Mastaba K1 at Beit Khallaf, dated to the reign of Netjerikhet, none the less yielded a sealing of Peribsen (Garstang 1902: pl. X.8). An unprovenanced cylinder vessel of red limestone is decorated with the

serekh

of Peribsen in raised relief (Kaplony 1965:24 and 26, fig. 51 [line drawing], pl. V fig. 51 [photograph]). Curiously, the name of Peribsen also occurs on a stone vessel fragment found by Petrie in the First Dynasty tomb of Merneith (Petrie 1900: pl. IV.7). The only possible explanation is that it represents later contamination of the tomb contents, perhaps from Amélineau’s excavations.

Other books

Animal Heat: A Paranormal Romance (The Animal Sagas) by Charles, Susan G.

Clubbed to Death by Ruth Dudley Edwards

August: Mating Fever (Bears of Kodiak Book 2) by Selene Charles

Forever Man by Brian Matthews

The Shoggoth Secret - Lovecraftian Erotica by Amy Morrel

Rendezvous in Rome by Carolyn Keene

Frenzy (The Frenzy Series Book 1) by Casey L. Bond

Saving a Wolf: Moonbound Series, Book Six by Camryn Rhys, Krystal Shannan

Motor City Mage by Cindy Spencer Pape

The Cottage Next Door by Georgia Bockoven