Early Dynastic Egypt (55 page)

State versus local religion

As for Egyptian religion of later periods, so cult of the Early Dynastic period must be divided into two categories: state and local. Not until the end of the Old Kingdom were local temples systematically ‘appropriated’ by the state, to be rebuilt and decorated in the formal style of the court as a way, no doubt, of binding the provinces more securely to the king and his government (cf. Kemp 1989:65–83). Throughout the Early Dynastic period it seems that the religious concerns of the court on the one hand and local communities on the other were entirely separate, and occasionally opposed. Local shrines served local communities, acting as foci for personal piety and probably for acts of collective worship at times of joy or trial. The character of community worship makes it likely that local shrines would have been accessible to the general public, at least as far as the forecourt. By contrast, temples built by and for the state were characterised by their exclusivity. This was emphasised in the architecture, a high enclosure wall restricting access to the temple in its entirety. A clear example of this is the rectangular enclosure- wall built around the temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis. In form it is similar to royal funerary enclosures of the Early Dynastic period, and its construction—effectively rendering the temple ‘off limits’ to the local population—may be connected with the programme of royal building work undertaken at Hierakonpolis by Khasekhem(wy). Whilst local cult activity was by its nature inclusive, state religion (in which royal cult played a large part) relied upon being exclusive (cf. Baines 1991:104).

Personnel

Little is known for certain about the personnel involved in Early Dynastic religion, national or local. Specific, if obscure, titles such as

s(t)m

and

sm3

are attested from the First Dynasty (Petrie 1901: pl. X.2; Emery 1958:31).

The leopard-skin garment worn by the

s(t)m

-priest has led one scholar to speculate that this figure was originally a shaman, practising more intuitive, magical rites, before the institutionalisation of a more ‘ordered’ religion at the beginning of the First Dynasty (Helck 1984d). There may also have been a connection between the

s(t)m

-priest and the goddess Seshat, who is often depicted wearing the same leopard-skin garment (Wainwright 1941:37). In later periods, the

s(t)m

-priest officiated at funerals, particularly in the ‘opening of the mouth’ ceremony (for example, Reeves 1990:72–3). This connection, together with the high status of the title

s(t)m

in the Early Dynastic period, has led to the suggestion that the holder of the office was the king’s eldest son and heir, second only in rank and authority to the monarch himself (Schmitz 1984:834). Indeed, as the person responsible for intimate royal rituals, the

s(t)m

would very likely have been a close member of the royal family.

A specialist class of funerary priest,

zh nw-3h ,

is also attested from the early First Dynasty (Petrie 1900: pl. XVI.119, 1901: pl. XV.111; Emery 1954:170, fig. 229), responsible for maintaining the mortuary cult of the king (and perhaps also of those of senior members of the royal family). The more general designation for priest,

hm-n r,

first occurs in the reign of Qaa at the end of the First Dynasty (Emery 1958:31, pl. 37.9). During the Second Dynasty we meet for the first time the title

h rỉ-hbt,

‘lector-priest’ (Amélineau 1902:144, pl. XXII.8; Lacau and Lauer 1959: pl. 14 no. 70). This in turn implies the formulation of theological texts and a role for the written and spoken word in cult practice. In general, however, the role of myth and dogma in early Egyptian religion was probably restricted, ritual being of primary importance in cult celebration. It has been argued that, prior to the Second Dynasty, the

s(t)m-priest

acted as keeper of ritual texts, but that this role was taken over by the newly created position of ‘lector-priest’ (Helck 1984d: 106).

Specialised priesthoods serving the major state cults seem to have emerged at the end of the Second and during the Third Dynasties. The title

wr-m3(w),

literally ‘greatest of seers’, held in later periods by the High Priest of Ra at Heliopolis but perhaps originally a title relating to astronomical observation, is first attested in the reign of Khasekhemwy (Amélineau 1902:144, pl. XXII.8); it was subsequently held by Imhotep, chancellor at the court of Netjerikhet. The title held by the High Priest of Horus of Letopolis,

wnr,

first appears at the end of the Third Dynasty (Goedicke 1966), as does the office of

h rp pr- wr,

‘controller of the Perwer (the national shrine of Upper Egypt)’ (Weill 1908:262–73).

A professional priesthood serving local cults is not attested until the Fifth Dynasty (Hornung 1983:226). However, there is evidence from the Early Dynastic period for the (part-time) priests of local cults holding important positions within their communities (Seidlmayer 1996b: 118). Thus, an individual named

Nmtỉ-htp,

owner of a large, richly furnished stairway tomb of the late Third Dynasty at Qau (Brunton 1927: pl. 18), is identified as a priest, presumably of the local cult (Seidlmayer 1996b: 118). Temples played an important role in local and national economies from an early period, and it is likely that temple personnel benefited materially, as well as in prestige, from an involvement with the local cult.

Royal cult

The ivory comb of Djet ‘presents concisely and clearly the central tenet binding together ancient Egyptian civilisation, the notion that the king fulfils a role on earth under the protective wings of the celestial falcon in heaven’ (Quirke 1992:21–2). The primary role of the king was as arbiter between the gods and the people of Egypt. In return for daily offerings and the celebration of their cult on earth, the gods looked favourably on Egypt and bestowed on the country their divine blessings. The channel of communication in this two-way process was the king. In theory, therefore, the king was the ultimate high priest in every temple in the land: ‘all cult in Egypt was royal cult’ (Quirke 1992:81). Implicitly, all temples were monuments to the king as well as cult centres for the deities to whom they were explicitly dedicated (Quirke 1992:81; cf. Fairman 1958:76). In discussing royal cult, therefore, a distinction must be made between the cults of deities which were in theory maintained by the king, and worship of the king himself as intermediary between the divine and human realms. The worship of the various gods and

goddesses is discussed below. The following discussion focuses on the cult of the king himself.

Royal cult statues

Several depictions of royal statues are known from Early Dynastic sources, indicating that the royal cult was celebrated, at least in part, by means of statuary (Figure 8.4). The earliest certain example dates to the reign of Den (Eaton-Krauss 1984:89). A seal- impression from Abydos shows three royal figures, each of which stands on a base-line (Kaplony 1963, III: pl. 93, fig. 364; F.D.Friedman 1995:33, fig. 19b). The accompanying hieroglyphs describe the statues as being made of gold. The manufacture of royal statues from metal is also attested in the late Second Dynasty (see below). On the Den sealing, the first figure wears the white crown and beard, holds a staff and mace, and is in a striding posture. The second figure wears the red crown and beard, and stands in a

papyrus skiff

in the act of harpooning a hippopotamus. It may be compared with two gilded statuettes from the tomb of Tutankhamun; these show the king in a similar posture of harpooning, although the object of the hunt (the hippopotamus) is not shown (Eaton- Krauss 1984:90). The third figure on the Den sealing shows the king wearing the red crown and

šndỉt

-kilt, in the unparalleled posture of wrestling with a hippopotamus. A link has been made between these last two representations and the entry for the reign of Den on the Palermo Stone which records a hippopotamus hunt. A further seal-impression of Den, from the tomb of Hemaka at Saqqara, may also show statues of the king (Emery 1938:64, fig. 26). Two royal figures are shown in striding or running posture, one wearing the red crown and one the white crown. A ground-line beneath the figures— which does not continue under the animals shown between them—suggests that they are to be interpreted as statues, since human figures on Early Dynastic sealings do not usually stand on a ground-line (Eaton-Krauss 1984:91). Comparable statues of the king in a striding or running posture are shown in the workshop scenes in the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Rekhmira (Davies 1943: pls 36, 37; F.D.Friedman 1995:33, fig. 19e). A seal- impression from the tomb of Djer may show a similar striding statue (Petrie 1901: pl. V.17), but the rudimentary publication of the sealing makes a certain identification impossible (Eaton-Krauss 1984:92, n. 484). If proven, the sealing would be the earliest representation of a royal statue, antedating the seal-impressions of Den by two generations.

Six incised stone vessels of Anedjib depict royal statues. Three of these, from Saqqara, bear identical inscriptions, showing a striding figure wearing the red crown, beard and kilt, holding a mace and the

mks

-staff. An inscription from Abydos differs only in that the king wears the white crown. A locality is named in association with the figures, and this probably indicates the cult place where the royal statues were kept. The stone vessels are likely to have belonged to the ritual equipment attached to the royal statue cult (Eaton- Krauss 1984:93). A rough and partially preserved inscription of Anedjib’s reign occurs on a stone vessel fragment from the Step Pyramid complex. It shows a striding figure in the act of harpooning. The head is lost, but, given the parallels from the preceding reign, it almost certainly showed the king (Eaton-Krauss 1984:94).

The fashioning or dedication of another royal statue is recorded in a well-known entry on the Palermo Stone. The statue depicted the last king of the Second Dynasty and was

called

q3-H -sh mwỉ,

‘high is Khasekhemwy’. The inscription states that it was made of copper; it may be compared with the life-size copper statue of Pepi I, found in the temple at Hierakonpolis (Quibell and Green 1902: pls L-LII; Sethe 1914). Some doubt surrounds the identification of the reign in which the statue of Khasekhemwy was commissioned. Some scholars favour Khasekhemwy’s successor (for example, Kaiser 1961), but it seems more likely that Khasekhemwy himself had the statue made (W.S.Smith 1971:147). The royal statues attested from the reigns of Den and Anedjib are examples of kings commissioning statues for their own cults. The creation of large-scale metal sculptures illustrates the technological sophistication of Early Dynastic craftsmen.

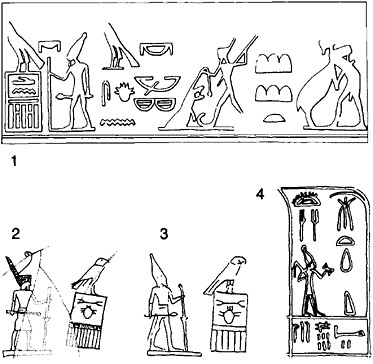

Figure 8.4

Royal cult statues. Evidence for the production and dedication of royal sculpture in the Early Dynastic period: (1) seal-impression of Den from Abydos showing three statues of the king engaged in various ritual activities; the accompanying inscription states that the statues were made of gold (after Kaplony 1963, III: fig. 364); (2) (3) inscriptions on stone vessels of Anedjib from the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerikhet; two

statues of the king are depicted, one wearing the red crown, the other wearing the white crown (after Lacau and Lauer 1959: planche III. 1–2); (4) entry from the fifth register of the Palermo Stone, referring to a year (in the reign of Khasekhemwy or his successor) as ‘the year of dedicating the copper statue “high is Khasekhemwy”’; this entry indicates that copper statuary was created long before the well-known images of Pepi I and Merenra found in the temple at Hierakonpolis (after Schäfer 1902: pl. I). Not to same scale.

The six relief panels installed beneath the Step Pyramid and South Tomb of Netjerikhet’s mortuary complex may depict royal statues rather than the king himself (F.D.Friedman 1995:32). The close parallels between one of the panels and the stone vessel inscriptions of Anedjib described above seem to support this hypothesis. A relief fragment of Netjerikhet from Heliopolis, showing the king enthroned and accompanied by three royal ladies, may also depict a royal statue, but this is not certain (Eaton-Krauss 1984:95).

Buildings of the royal cult

The construction of buildings for the royal cult seems to have been the most important project of each reign, absorbing much of the court’s revenue. Hence, the size of the royal mortuary complex offers a guide both to Egypt’s prosperity and to the power of the central government to exploit the country’s resources. Moreover, the increasing elaboration of royal cult buildings from the Predynastic period onwards is ‘one of the most socially, economically and politically sensitive indicators of the rise of the state’ (Hoffman 1980:336). The surviving buildings of the Early Dynastic royal cult are characterised in general by their apparent mortuary nature. The large enclosures of the First and Second Dynasties at Abydos, Saqqara and Hierakonpolis are usually termed ‘funerary’, and the Step Pyramid complex of Netjerikhet is regarded as having fulfilled a primarily mortuary role. However, the picture may not be so simple. There is evidence from the Old Kingdom to indicate that the royal cult at a pyramid was celebrated during the lifetime of the reigning king. Furthermore, the decoration of Old Kingdom royal ‘mortuary’ temples does not focus on funerary themes, but on the ritual duties and festivals of kingship, especially the Sed-festival (Seidlmayer 1996b: 122). The same appears to be true of the surviving relief fragments from the Hierakonpolis enclosure of Khasekhemwy, and of the six relief panels from the Step Pyramid complex. It is possible, therefore, that the Netjerikhet complex, and some if not all of its First and Second Dynasty antecedents, was used for the celebration of the royal cult before the king’s death.

Other books

Blood Judgment (Judgment Series) by Asher, Nickie

A Film Star, A Baby, And A Proposal by CC MacKenzie

Open Wide by Nancy Krulik

Smart Girl by Rachel Hollis

Swimming with Sharks by Neuhaus, Nele

3: Black Blades by Ginn Hale

Hot Property (Irish romantic comedy) by O'Leary, Susanne

The Purgatorium by Eva Pohler

Sweets for Sale: A Rough Stranger Sex Erotica Story by Sanders, Amy

Septimus Heap 4 - Queste by Sage, Angie