Eat the Rich: A Treatise on Economics (17 page)

Read Eat the Rich: A Treatise on Economics Online

Authors: P.J. O'Rourke

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Business, #Humour, #Philosophy, #Politics, #History

The government of Cuba, with force aplenty at its disposal, decided that beef cost too much. The price of beef was fixed at a very low level, and all the beef disappeared from the government ration stores. The people of Cuba had to hassle tourists to get dollars to buy beef on the black market, where the price of beef turned out to be what beef costs.

When the price of something is fixed below market level, that something disappears from the legal market. And when the price of something is fixed above market level, the opposite occurs. Say the customers at suburban Wheat Depot won’t pay enough for wheat. The U.S. government may decide to buy that wheat at higher prices. Suddenly there’s wheat everywhere. It turns out that people have bushels of it in the attic. The government is up to its dull, gaping mouth in wheat. The wheat has to be given away. The recipients of free wheat in the Inner City Wheatfare Program hawk the wheat at traffic lights, and what they get for it is exactly what people are willing to give.

3. You Can’t Get Something for Nothing.

Everybody remembers this except politicians. Lately, it has been the fashion for American politicians to promise that government revenue—taxes—can be cut while government benefits—expenditures—remain intact. Benefits might even get larger. This will be done through efficiency, as if politicians are all going to invent the steam engine. Though, to the extent that steam is hot air, predictable jokes are invited.

Politicians have trouble giving up the idea of something for nothing; it’s such a vote catcher. A government can give most people something for nothing by taxing the few people with money. This is how Sweden has gotten into trouble. There are never enough of those people with money. And the people with money are the people with accountants, tax lawyers, and bank accounts in Luxembourg, so they end up not paying their taxes. Or even if they do pay their taxes, like good Swedes, the people with money are also the people who know how to manipulate the system. Therefore, instead of the situation that Samuelson posited in

Economics

where “modern democracies take loaves from the wealthy and pass them out to the poor,” we get a situation where loaves are taken from the wealthy and subsidized opera tickets are passed back to them.

A government can give all people something for nothing by simply printing more money. This doesn’t work, because it makes all the money worth less, as it did in Wiemar Germany, Carter America, and Yeltsin Russia. Inflation is a tax on the prudent, who watch the value of their conservative savings-bond and bank-account investments disappear. It’s a subsidy for the “big, swinging dicks” who can borrow money for harebrained speculatory schemes and pay it back later with cheap cash. And it’s a punishment to the old and the poor, who live on fixed incomes and who can’t expect to get a big cost-of-living adjustment retrieving soda cans from trash baskets.

Finally, a government can give us something for nothing by running a deficit, by borrowing money from everybody and then giving everybody his money back, plus interest. This is obviously stupid and exactly what we’ve been doing for decades in the United States. Deficits are less immediately painful than high inflation or huge taxes, although eventually they lead to one or the other, or both. In the meantime, we’re not getting anywhere. If all our investment money is tied up in loans to the government, that money is going to be spent on government things, such as financing the Inner City Wheatfare Program. Our investment money can’t be spent on research and development to create a genetically engineered wheat-eating squid to turn that worthless wheat into valuable calamari.

4. You Can’t Have Everything.

If you use your resources to obtain a thing, you can’t use those same resources to obtain something else. That’s called fraud (or having a credit card). In economics its called “opportunity cost.” When you employ your money, brains, and time in one way, it costs you the opportunity to employ them in another. Opportunity costs fool people because they’re unseen. When we observe money being spent, we’re impressed. We gasp with awe at the huge new Federal Wheat Council headquarters in Washington, D.C. We don’t admire the vast schools of squid feeding in our nation's wheat fields—because they aren’t there. The main cost of government expenditure is not taxes, inflation, or interest on the national debt. The main cost is opportunity.

Sweden is a case in point. The Swedes like what their government does. They look around Sweden and see handsome government buildings, nice government programs, and generous government benefits. What they look around and don’t see is what Sweden might have been if all that money had been invested in businesses and industries. From 1968 to 1969, before Sweden got carried away with its socialism, the country’s per-capita gross domestic product grew by 5.7 percent. What if the Swedes had kept that up, or for the sake of mathematical simplicity, improved it a bit? As organized and self-disciplined as the Swedes are, why not? What if the Swedish per-capita GDP had been growing by 6 percent annually for the past thirty years? Swedes, who are now about 27 percent poorer than Americans, would be more than three times as wealthy as we are. They’d have a per-capita GDP of more than $66,000. They’d be richer than the people of any country have ever been. And Sweden, with a population of only 9 million, would be one of the world’s great economic powers. Volvo would be winning the Daytona 500, Saab would have space stations, IKEA would furnish the homes of the Hollywood stars, and Swedish-massage therapy would be the most popular form of medical treatment on earth.

5. Break It and You Bought It.

Being fooled by hidden costs is the source of a lot of economic confusion. War is often spoken of as an economic stimulant. World War II “pulled America out of the Depression.” Germany and Japan experienced “economic miracles” after the war. Somebody is not counting the cost of getting killed and wounded. Besides, if destruction were the key to greater economic productivity, every investor on Wall Street would be learning Albanian.

6. Good Is Not as Good as Better.

Almost as bad as costs that go unnoticed are benefits that get too much attention. It’s great if everybody has a job. Computers are taking jobs away. We could guarantee full employment if we removed computers—and electricity, too—from the telephone companies and hired people to run all over town and fly around the world, telling our friends and business associates what we want to say.

When James Watt invented that steam engine, thousands of ten-year-old boys who had been hauling coal carts were put out of work. However, this left them free to do other things, such as live to be eleven.

7. The Past Is Past.

Another thing that gets too much attention is money that’s already been spent. In economics this is called “sunk costs.” It doesn’t matter that you blew everything you made selling Apple at $1,000 a share on a scheme to genetically engineer squid. What matters is whether you can make any money off those squid now or convince people that the squid will make money in the future, so that those people will buy the fool company. This is called “marginal thinking,” and on Wall Street it means almost the exact opposite of what we usually mean when we call someone a marginal thinker.

8. Build It and They Will Come.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was referring to better mousetraps, and the idea that the world would beat a path to your door for one tells us something about home hygiene in the nineteenth century. The underlying notion is stated formally in economics as Say’s Law (after French economist Jean Baptiste Say, 1767–1832): “Supply creates its own demand.” More is better. Any increase in productivity in a society causes that society to get enough richer to buy the things that are produced.

This works even in an economy as screwed up as Cuba’s. The Cuban authorities allowed limited free-market sales of food, and this increased food production. Despite the extreme poverty of Cubans, that food did not sit around unsold.

9. Everybody Gets Paid.

People want to get something for what they do, although what they want to get may not be money—it may be sex or salvation or an opportunity to apply marxist theory to rock and roll. Everything is a business.

This is the “public choice” theory of economics. One of its founders, James M. Buchanan, won the 1986 Nobel Prize in economics for his work on understanding politics as an economic activity. Politicians don’t measure profits in cash. The gain that they want is an increase in power. Thus the socialists of Sweden and Cuba are just as greedy as the pirates of Wall Street and Albania.

In order to increase their “power income,” politicians have to pass more legislation, expand bureaucracies, and broaden the scope of government power. This power income is what the Swedish cabinet minister Marita Ulvskog was really talking about when she told me, “You have to give something to voters.” Of course, that something can be, if you like, measured in money—

your

money, the money that government costs you in taxes, deficits, or currency inflation. Anyway, a politician who claims he’s going to cut the size of government is saying he’s going to creep up on himself and steal his own wallet.

10. Everybody’s an Expert.

Of all the principles of economics, the one that’s most important to making us richer (or more powerful or whatever) is specialization, or “division of labor.” Milton Friedman uses a pencil as an example. A pencil is a simple object, but there’s not a single person in the world who can make one. That person would need to be a miner to get the graphite, a chemical engineer to turn graphite into pencil lead, a lumberjack to cut the cedar trees, and a carpenter to shape the pencil casing. He’d need to know how to make yellow paint, how to spray it on, and how to make a paint sprayer. He’d have to go back to the mines to get the ore to make the metal for the thingy that holds the eraser, then build a smelter, a rolling plant, and a machine-tool factory to produce equipment to crimp the thingy in place. And he’d have to grow a rubber tree in his backyard. All this would take a lot of money. Yet a pencil sells for nine cents.

The implications of division of labor are surprising, but only if we don’t think about them. If we do think about them, they are, like most economic principles, a matter of common sense. There are, however, a few things about economics that don’t seem to make sense at all. Todd G. Buchholz, in his book

New Ideas from Dead Economists,

says, “An insolent natural scientist once asked a famous economist to name one economic rule that isn’t either obvious or unimportant.” The reply was “Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage.”

The English economist David Ricardo (1772–1823) postulated this: If you can do X better than you can do Z, and there’s a second person who can do Z better than he can do X, but can also do both X and Z better than you can, then an economy should

not

encourage that second person to do both things. You and he (and society as a whole) will profit more if you each do what you do best.

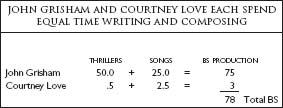

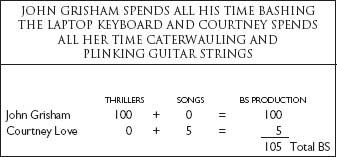

Let us decide, for the sake of an example, that one legal thriller is equal to one pop song as a Benefit to Society. (One thriller or one song = 1 unit of BS.) John Grisham is a better writer than Courtney Love. John Grisham is also (assuming he plays the comb and wax paper or something) a better musician than Courtney Love. Say John Grisham is 100 times the writer Courtney Love is, and say he’s 10 times the musician. Then say that John Grisham can either write 100 legal thrillers in a year (I’ll bet he can) or compose 50 songs. This would mean that Courtney Love could write either 1 thriller or compose 5 songs in the same period.

If John Grisham spends 50 percent of his time scribbling predictable plots and 50 percent of his time blowing into a kazoo, the result will be 50 thrillers and 25 songs for a total of 75 BS units. If Courtney Love spends 50 percent of her time annoying a word processor and 50 percent of her time making noise in a recording studio, the result will be 1 half-completed thriller and 2.5 songs for a total of 3 BS. The grand total Benefit to Society will be 78 units.