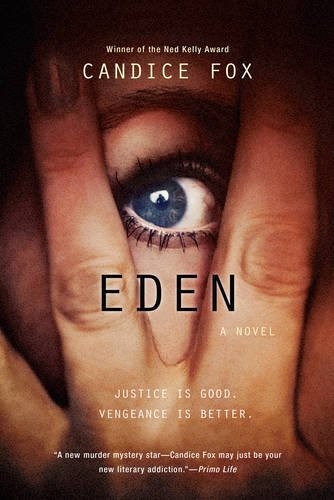

Eden

Authors: Candice Fox

Praise for Candice Fox

EDEN

“Candice Fox’s first novel,

Hades

, announced the arrival of an important new voice in Australian crime fiction. It won the Ned Kelly Award for best first fiction in 2014, with the judges complimenting the author on her genre-bending blend of horror and crime.

Eden

is equally breathtaking in its audacity. This is crime fiction informed not so much by the literary past of the genre, as by television’s

Dexter

and

Breaking Bad

, the ironically violent films of Quentin Tarantino and the graphic novels of Frank Miller. Sydney emerges from Fox’s pages as an antipodean

Sin City

.”

Hades

, announced the arrival of an important new voice in Australian crime fiction. It won the Ned Kelly Award for best first fiction in 2014, with the judges complimenting the author on her genre-bending blend of horror and crime.

Eden

is equally breathtaking in its audacity. This is crime fiction informed not so much by the literary past of the genre, as by television’s

Dexter

and

Breaking Bad

, the ironically violent films of Quentin Tarantino and the graphic novels of Frank Miller. Sydney emerges from Fox’s pages as an antipodean

Sin City

.”

—

Sydney Morning Herald

Sydney Morning Herald

HADES

“Horrors abound in Australian author Fox’s first novel, a gritty police procedural set in Sydney. In this twisted noir world, love goes as wrong as it can go. Readers will look forward to the sequel set in this not-for-the-squeamish nightmare world down under.”

—

Publishers Weekly

Publishers Weekly

“Fox’s fast-paced first novel, with its unusual protagonists and dark, disturbing scenes stands on its own. Readers will anticipate eagerly the planned sequel.”

—

Library Journal

Library Journal

“Compelling . . . Candice Fox makes a strong debut in a series about a serial killer. Exploring the concept of whether killing for justice could ever be rationalized,

Hades

is a chilling read.”

Hades

is a chilling read.”

—

Sydney Morning Herald

Sydney Morning Herald

“A frighteningly self-assured debut with a cracker plot, strong characters, and feisty, no-nonsense writing.”

—Qantas

magazine

magazine

“A powerful book, an incredible read. The pace is extreme, the violence and the fear are palpable. The plot is original and twisted; black and bloody. Tension runs riot on the page. Dexter would be proud!”

—The Reading Room

“Well written with a suck-you-in story and characters with depth,

Hades

is an exciting read, a bit

Dexter

-ish. It moves at a great pace and reveals the narrative twists and turns in a way that keeps you playing detective as you read—and it has an outcome I didn’t see coming. It’s a great debut novel.”

Hades

is an exciting read, a bit

Dexter

-ish. It moves at a great pace and reveals the narrative twists and turns in a way that keeps you playing detective as you read—and it has an outcome I didn’t see coming. It’s a great debut novel.”

—The Co-op Online Bookstore: Staff Picks

“A dark, compelling, and original thriller that will have you spellbound from its atmospheric opening pages to its shocking climax.

Hades

is the debut of a stunning new talent in crime fiction. The narrative is engaging, compelling. The characters are unique and well fleshed out. The story is strong, bold, amazing. This is how a crime thriller should make you feel.”

Hades

is the debut of a stunning new talent in crime fiction. The narrative is engaging, compelling. The characters are unique and well fleshed out. The story is strong, bold, amazing. This is how a crime thriller should make you feel.”

—Reading, Writing and Reisling

“Candice Fox grew up trying to scare her friends with true-crime stories. If her intent was to try and create an at times chilling and gruesome story as her debut, it is very much mission accomplished. She certainly looms as an exciting new prospect in the ranks of Australian authors.”

—

Western Advocate

Western Advocate

“

The unfolding story of the characters (Eden, Eric, and Frank) had me eagerly turning page after page.”

The unfolding story of the characters (Eden, Eric, and Frank) had me eagerly turning page after page.”

—debbish dotcom

A

LSO

B

Y

C

ANDICE

F

OX

LSO

B

Y

C

ANDICE

F

OX

Hades

EDEN

CANDICE FOX

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For Tim.

The night of the boy’s murder he was working, wandering along Darlinghurst Road in the crowds of workers, picking pockets, begging, doing stunts for coins. Later the boy would think of his life in the city streets as the Winter Days, because even in the summer they seemed cold and damp, the daylight short.

It took years for the boy to forget how to remember, when one day ate into the next and nothing broke the monotony except the stabbing death of a whore or the chance find of a coin on the concrete. The sun shuttered above the buildings, on and off, counting the days. The boy wandered, head down, practiced at sniffing bins outside restaurants to identify treasures hidden within, at slipping through cinema fire exits to search for popcorn and sweets, at scaling tall buildings to raid clotheslines strung across cramped balconies.

Sometimes the boy felt he could have been ancient because all that came before the Night of Fire and Screaming was darkness. Now and then when he slept he returned to the fire, saw the faces of the woman and the man he supposed must have been his parents against the windows, heard their pounding on the glass behind the bars. Whenever he tried to remember how long ago the fire happened, who those people were and why they had died, how he had survived and how he had got to the city, he was confronted by blackness—a door closed, locked, impassable. He didn’t know how old he was or the name those screaming people called him. When the police and the kindly women who had spotted him came to take him, they said he looked eight. He was happy with that. They’d also said he was mute and malnourished, but he didn’t know what either of those things were. He’d fled the van they put him in and kept his eye out from then on. He didn’t like the police. He didn’t know why.

He wandered and tried to forget.

On the night he met the French Man, the boy was sitting on a set of steps down from The Goldfish Bowl, which was alive with laughing and shoving, the toppling of glasses, the slapping of beer caps onto the pavement.

The French Man came walking up the hill under the Moreton Bay fig trees, the smoke from his cigarette winding around a row of sailors advancing behind him. The boy moved off the steps and headed down to meet the sailors, stretching his dirty face into his brightest smile. The French Man caught him by the elbow and spun him in a half circle. The sailors parted to let him through.

“What’s the hurry, petit monsieur?”

The boy wasn’t fussy who his marks were. The French Man didn’t look like a cop, so he would make an easy meal. His accent was slurred and heavy. Perhaps he’d been drinking down at the waterfront. He smelled of cigarettes and wine, but his hair was neatly combed so that the ridges stood out across his curved scalp.

“Hello, sir! Got a coin?” the boy asked. “I can dance, I can sing, I can tell jokes. I can balance a penny on my nose.”

The boy did a handstand and walked in a circle on his palms on the dirty pavement. His black-soled feet waggled in the air. The French Man folded his arms and laughed, and a couple walking their dog stopped to watch.

“That’s very good, Monsieur,” the French Man smiled. “What else can you do?”

“I can make a coin disappear,” the boy boasted.

The couple laughed. Two other men stopped to watch. The French Man fished a penny from his pocket and handed it to the boy.

“Abracadabra, hocus pocus!” The boy swirled his arms in the air. Everyone smiled. He slipped the copper into his sleeve and dropped to one knee.

“Ta daa!”

“Magnifique!” The French Man clapped his long thin hands. “Now give it back.”

“I can’t,” the boy claimed. “It’s disappeared.”

More laughter. The boy did another handstand as the crowd clapped and then dispersed. The French Man remained, his thin lip curled slightly at the corner.

“Another coin for the show?” the boy asked.

“I’m afraid I’m fresh out. Plucked me dry. Are you hungry, boy?”

“Starving.”

“Come on, then. This way. I’ve got a fresh batch of sausages waiting for me at home. Two streets back.” The French Man flicked his head toward the crest of the hill. “You’re welcome to a bite, little friend. Most welcome.”

The French Man kept walking as though he didn’t mind leaving the boy in the wind-swept street. The boy looked down the hill and saw no more sailors coming. As it swung back and forth, the French Man’s wrist glittered with a silver wristwatch. The boy licked his lips, brushed aside his fear, and followed.

Rain was dripping in silver streams from the corrugated iron roof of the terrace house in Ithaca Road. The boy huddled close to the French Man as the wind rippled through the huge figs. He tried to get a feel for a wallet or a coin purse as he brushed and bumped against the man’s side. There was none. The boy circled the man, sometimes ahead, sometimes behind. The French Man laughed and ruffled his hair.

“You’re a small boy. Got to bend to get ahold of you. Quick as a ferret.”

“How many sausages will there be?”

“Enough for a belly as small as yours. You’ve got an accent to you. Sauerkraut, is it?”

The boy shrugged. He knew he spoke funny but he didn’t know why.

They stepped up onto the porch. The French Man jangled his keys. Inside, the house smelled damp, as though something in the walls was rotting and about to drip out of the wallpaper. The boy skittered down the hall to a table under a grimy kitchen window. It was covered with shining, glimmering things. The boy looked over the mess and tried to pick something to lift before the man caught up. He pocketed a shiny lens. There was a paper bag stuffed with small square photographs. The boy glimpsed bare limbs, naked chests. When he put his hand on the bag the French Man brushed it away.

“What is all this stuff?”

“This, my small friend, is the Polaroid 110B, the Pathfinder. Newest thing on the market. It develops pictures instantly. Poof! Right in your hand. Like magic,” the French Man said, and winked. He picked the camera out of the clutter and held it in the light. “You don’t have to go to a store. You can develop your own pictures, right here, at home.”

“Are you a photographer?”

“Sometimes, yes.”

The boy let his eyes wander to the French Man’s face. There were scars on his cheeks from burns or acne, marbling the surface of his high cheekbones. “Here. You take a picture of me and I’ll take one of you.”

The boy giggled and took the heavy camera in his small chubby hands, turned it, looked through the viewfinder. The French Man struck a pose. The device hummed and zinged in the boy’s hands, seemed to zap like an alien thing. Light exploded off the walls. The camera spewed out a blank picture, which gradually rippled with light. The boy watched it develop with barely contained rapture. Magic. The boy let the camera go with reluctance.

“Your turn.”

He smiled and struck a pose. The flash burned against the backs of his eyelids. He wondered if he’d ever had his picture taken before the Night of Fire and Screaming, if there were pictures of him somewhere still, smiling and playing. The thought made the boy a little sad. The French Man snapped another picture of him standing and staring at the floor.

“You ever seen Sugar Ray? The boxer?”

“Course I have!”

The boy clenched his fists and hung them above his head, his puny biceps flexed as small cream-white lumps on his stringy arms. The French Man laughed and snapped a shot. The boy growled and brought his fists together at his belly. Another zap, hum, a spewed picture. The French Man flipped the photos onto the table without looking at them. The boy laughed nervously, shifting from foot to foot. The room seemed a little small, suddenly. The French Man snapped another picture, and the boy forgot to pose. He was simply standing there. Being him.

“Take your shirt off.”

The boy frowned a little. He slipped the shirt over his head, smelling it as the cloth passed his nose, three days or so of sweat and scum and rain. The boy cupped his hands and did a pose of his side as he had seen the boxers do. The French Man snapped him.

“I’m hungry.”

“Just a few more.”

The boy sighed. More pictures. The air in the room was hard to breathe. His cheeks felt hot. He didn’t know why.

“It’s no fun anymore. Let’s eat.”

The French Man snapped him again, crouching by the table, eye level with the boy. The light made the boy’s eyes water. He reached out and pulled the camera down. The man lifted it again.

“A few more.”

“No.”

“You want to eat, you do as I say,” the French Man grunted, showing teeth. The two front ones were gray as steel. The boy looked down the hall at the front door, so far away the darkness swallowed it, giving only a slice of silver at the bottom where the moonlit street blazed. “We’re friends, aren’t we, boy? Good friends. Friends don’t argue with each other.”

The camera flashed again. Now the pictures were falling on the floor. The boy picked his shirt up. His fingers were numb, the blood raging in his ears. Embarrassed, somehow. The French Man’s fingers flashed out, ripped the cloth from his fingers, and flung the shirt by the pile of pictures. The boy’s face stared up from the photos. Afraid.

“I’ve got to go.”

“You’re not going anywhere.”

“I said, I want to go!”

The slap came like a burst of heat, soundless, before the boy knew what had happened. His ear pulsed, hammering against his head. The French Man shook his head slowly, sadly, then reached up and took the boy’s face in his cold hand.

“Don’t disappoint me, pretty one.”

The boy turned, twisted, tried to scramble away. They collapsed to the floor, the man a dead weight. The air was squeezed out of him. His stomach churned, clenched, tried to suck oxygen into his lungs. His mouth was on the floor, lips collecting dust.

“You do what I say, when I say.”

The French Man pinned his neck against the boards, righted the camera in his other hand. The boy kicked out, struck the table leg, pain flooding his bones. The man snapped another shot, then placed the camera beside his face.

The boy reached out, sweeping it into his arm. In the same movement he rolled beneath the weight of the man and used the momentum to swing the camera up and over, into the side of the man’s head.

Then the Silence came.

He had felt the Silence only once before—on the Night of Fire and Screaming, when he had stood in the street motionless and watched the people burning. It felt something like being underwater, sounds pinging softly, all else an endless nothingness, slowed by numbness, decaying moments, the dripping of time.

The boy was on top of the French Man, the camera in his hands, beating it down on the man’s face over and over without sound, without sensation. The face was breaking, losing shape, becoming wet. The man’s hands were fumbling at his face and neck, scratching, wringing, twisting, punching. Time passed. The camera fell away. The boy used his fists.

When the door of the terrace opened the boy was standing by the table, looking down at a picture of himself standing by the table. When the men’s voices broke the Silence the boy lifted his head. There were shadows in the hall, one larger than the other, a great hulk of a man whose shoulders scraped the narrow walls and head ducked beneath the ornate frame of the kitchen door naturally, as though he’d been here before. A smaller man walked in front, cast in shadow by the beast. The boy wiped at a tickle on his upper lip. He looked at his hands. The blood was smeared to his elbows.

“Jean? Jean? You fucking frog prick. I know you’re here. Time’s up. I want my money, you hear me, cocksucker?”

The first man was wearing a suit the color of gray ocean. Beneath the suit, old muscle languished to fat, making him look like an elderly retired war captain, his once-powerful frame ruined by peacetime. His hair was gray and a deep groove was cut into his chin from a clean knife wound that had split his bottom lip in two. The giant was not as well dressed but gave the same impression of darkened skies and old wars, a bearded bear with a nose that dominated the front of his face, broken and twisted, a fighter’s nose.

The boy and the two men looked at each other, before all eyes fell away. The men took in the smashed and broken thing that had been Jean the French Man, lying twisted at the boy’s feet. There was a gun in the old captain’s hand, hanging by his side, forgotten. No one spoke. The boy lifted his palms and examined the blood on them, the mangled knuckles swollen twice their size, the wet and watery almost-orange blood sliding down his wrists.

“Well, would you look at this, Bear,” the Captain said.

The Bear said nothing as the Captain wandered forward and crouched beside the boy. He lifted a photo from the floor and flicked the blood from it. The boy standing. The boy with his biceps bared. He looked at them all, considered each in turn, laid them in a neat pile. Jean wasn’t breathing. The Captain stood and looked down at the boy.

Slowly, a smile crept across the Captain’s face. Then he began to laugh. The Bear wasn’t laughing. He wasn’t even smiling.

Other books

My Zombie Hamster by Havelock McCreely

Quarry's Deal by Max Allan Collins

The Money Is Green by Mr Owen Sullivan

Knightley and Son (9781619631540) by Gavin, Rohan

The Missing Italian Girl by Barbara Pope

La fría piel de agosto by Espinoza Guerra, Julio

Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev

Black Moon Draw by Lizzy Ford

Jersey Girl (Sticks & Hearts #1) by Rhonda James

The Great Altruist by Z. D. Robinson