Eden's Outcasts (8 page)

Authors: John Matteson

[In Philadelphia] our arrangements were such that opportunity for free, uninterrupted thought was almost impossible. My companion suffered from the same cause. We were thrown in

each other's

way. The children were thrown in

our way.

The effect on all was depressingâ¦. The space and freedomâ¦we ought to have had, was denied us. Intellectual progress was retarded, and health prostrated thereby.

31

Yet, the closer quarters meant that Anna now slept in her parents' room, and this arrangement improved her temper. However, she was still inclined to act more like a two-year-old than the avatar of divinity Bronson wanted her to become. At times, Bronson confessed, she was almost ungovernable. For her part, Louisa was more willful and wayward than Anna had been at the same age. Prone to fierce tantrums, she would throw herself on the floor and shriek when her desires were thwarted. Bronson's obsessive attention to parental behavior had also begun to undermine Abba's confidence in her motherly skills. “Mr. A. aids me in general principles,” she told her brother Samuel, “but nobody can help me in the detail.” Too often, Bronson's fastidious criticisms caused her to wonder, “Am I doing what is right? Am I doing too much?”

32

Committed in principle to her husband's theories of noncoercive parenting, she at last found that she could maintain order only by spanking. She even resorted to slapping Anna as a corrective measure. Observing Anna's new experience of what he gently called “power and pain,” Bronson surmised that Abba's use of force was only making matters worse.

33

With his domestic peace unraveling and his suppositions about child rearing being daily refuted, Bronson somehow found a way to press forward with his own education. As biographer Odell Shepard has observed, the Alcott who first made his way to Philadelphia in 1830 could make no claim to being a well-read man. By 1834, when he returned to Boston, he could hold his head up among the most studious people in the city. In addition to Coleridge and Plato, he was reading Pythagoras, Berkeley, Wordsworth, and Carlyle. However, it taxed him to keep up his reading while also running a school and helping to manage a chaotic household. Reluctantly, he finally did something that perhaps speaks better of his instinct for self-preservation than it does for his devotion to his family. For a brief period, he essentially ran away from home.

To be more precise, he split the family up, locating rooms for Abba and the girls back in Germantown while he took an attic room in the city. On weekends, he walked six miles each way to spend time with Abba and the girls. He was struggling to serve three masters at once: the necessity of earning a living; the care and nurture of his children; and the ceaselessly demanding appetite of his mind. Instead of intertwining, these three imperatives were tugging in opposite directions. Bronson had once complained that fathers were typically too remote from their families and “too often so much interested in personal matters that they give little time to the attention of their children.”

34

Now he was learning why this was true.

Nevertheless, he was able to persuade himself that the separation was best for everyone. The girls had fresh air and room for exercise. As for Abba, he hoped that a separation would restore the “subtle ties of friendship which are worn away by constant familiarity.” For his own part, Alcott greatly enjoyed his chamber in the city, whose window opened toward the rising sun and a stand of trees whose rich foliage trembled softly in the breeze.

35

Absorbing the peace and quiet of the scene, he made fine use of the time he spent alone. Branching into German Romanticism, he delved into Goethe, Schiller, and Herder and came to the conclusion that his ideas of teaching, while they had taken him in the right direction, had not gone far enough. In his 1830 essay on principles and methods, he had seen the juvenile mind as a succession of developing faculties, beginning with the animal nature and ending with the intellect. Coleridge and the great Germans showed him that he had stopped one step short of the end. The crowning achievement of education lay not in the culture of the understanding but in the perfection of the spiritual nature. Through symbolic stories and parables, he would henceforth lead his pupils to an awareness of their own divinity. He now needed only the proper venue to put his theory to the test.

It was now clear that this test would not be made in Philadelphia. Bronson had continued to try out unconventional teaching methods, including requiring his students to keep journals of their intellectual and spiritual progress. Mystified and, perhaps, faintly frightened by these kinds of assignments, parents began to withdraw their children from Alcott's tutelage.

36

By early May 1834, his school had lost forty percent of its enrollment, and further attrition was expected. In an attempt to rescue the venture, he called on all the parents who had disapproved of his methods. Decrying the evils of schools “where cunningâ¦was made the usual motive of action” and kindness and forbearance were derided as signs of weakness, he asked them to reconsider. They refused, leaving Alcott to console himself with dire predictions concerning the children snatched from his protective arms. Of one boy removed by his parents, Alcott wrote ominously, “[H]e will doubtless fall a victim to misdirected measures. Temptations will come in his way and he will yield. The good convictions of his mind will die away.”

37

He had been convinced for some time that his best chance for success was in Boston.

38

To help facilitate a return, he appealed to William Ellery Channing, the eminent Unitarian minister who had helped to underwrite Alcott's Common Street School six years earlier. Alcott's desire to found a new school first came to Channing's attention by means of a letter from William Russell, who swore that Alcott would inaugurate a “new era” in education. Channing arranged to meet with Alcott at his summer home in Newport, Rhode Island. The minister's earlier favorable impressions were confirmed. Channing enthusiastically embraced Alcott's proposed return to Boston and promised his financial backing. He promptly set about finding supporters for Alcott's school and had soon assembled an impressive list of interested parties, including Massachusetts Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw and Boston's mayor, Josiah Quincy. Both men not only pledged economic support but also agreed to enroll children in the school. Channing also arranged to send his own daughter Mary. Thus, in September 1834, the Alcott family retraced its steps to Boston. Before the month was out, Alcott had rented five rooms on the top floor of the Masonic temple on Tremont Street. With men like Channing, Shaw, and Quincy at his back, he could no longer call himself an obscure schoolmaster. Whether this School of Human Culture, known to all as the Temple School, brought its master renown or dishonor, it would do so under broad public scrutiny.

THE TEMPLE SCHOOL

“I say that the Christian world is anti-Christ.”

â

A. BRONSON ALCOTT,

Journals,

November 1837

W

INNING OVER THE LEADING CITIZENS OF BOSTON WAS

not the only brilliant stroke of fortune that attended the founding of the Temple School. For his teaching assistant, Alcott secured the services of Channing's former secretary, a young woman who stood in the first rank of New England minds. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody was the eldest of a trio of sisters who were to live at the very center of New England education and letters. The middle sister, Mary, became the wife of the titan of American public education, Horace Mann. The youngest, Sophia, married the great novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne. Elizabeth, by contrast, chose a grander object than a husband. She was intent on “educating children morally and spiritually as well as intellectually from the first.” It was, she knew, “the vocation for which [she] had been educated from childhood.”

1

Peabody was barely five feet tall, but people often had the sense that she was much taller. There was a largeness about her that expressed itself in the penetrating quality of her thought and the size of her ambitions. At the age of thirteen, she declared her desire to write her own translation of the Bible. At seventeen, she opened her first school. She dressed unconventionally and was typically too absorbed by her inner life and practical objectives to pay careful attention to her appearance. Incurably disheveled, forever on the move, Peabody was infuriated by those who maintained that education should be parceled out according to gender. She herself was a potent argument for the capacity of women to excel in disciplines traditionally reserved for men. She eventually became proficient in ten languages, including Latin, Sanskrit, Hebrew, and Chinese.

Bronson thought Peabody blessed with “the most magnificent philosophic imagination” of anyone he knew.

2

Peabody more than returned the compliment. She had first met Bronson in August 1828 and, around that time, favorably reviewed his school in Russell's

American Journal of Education

. “From the first time I ever saw you with a child,” she later told him, “I have felt and declared that you had more genius for education than I ever saw, or expected to see.”

3

Her opinion of him rose still higher when Bronson showed her the journals of his Philadelphia pupils. She wrote to her sister Mary that she was “

amazed

beyond measure at the composition” and concluded that Alcott had more natural ability as a teacher than anyone else she had ever met. She proclaimed him to be an embodiment of intellectual light and predicted that he would “make an era in society.”

4

At the Temple School, Alcott's magnetic charm with children was indisputable, and his conversational method of teaching worked marvelously at drawing out creative thought. As one of his pupils there was later to remark, “I never knew I had a mind till I came to this school!”

5

Peabody provided much-needed ballast for Alcott's lighter-than-air visions. Unlike him, she had learned a degree of caution from her previous battles with conservatively minded parents and had acquired a fairly accurate idea of when not to press an issue. She also possessed expertise in areas where Alcott was thoroughly unqualified. Alcott had no command of Latin and a precarious grasp of mathematics. Using only his own talents, he could never have mounted a curriculum acceptable to high-ranking Boston families. By contrast, Peabody was a bona fide classical scholar and more than capable with numbers. By rights, if one were to consider only the raw abilities of the two, Alcott probably should have been Peabody's assistant, not the other way round.

However, there was a curious wrinkle in Peabody's personality that led her to prefer the second position. Despite her natural assertiveness, she had perhaps internalized some of her society's bias in favor of male leadership. Although never humble or reluctant to express an opinion, she took satisfaction from locating men of unusual genius and idealism and offering her services as a faithful Sancho Panza. In attaching herself to Alcott, she not only accepted a subordinate position beneath her full capacities, but she volunteered to work for whatever wages Alcott might be capable of dispensing. She thus virtually assured herself of never being paid.

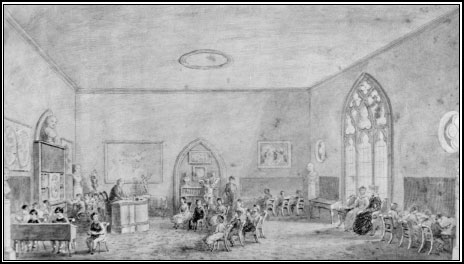

In the spacious upstairs room of Boston's Masonic Temple, Bronson Alcott and Elizabeth Palmer Peabody attempted to establish the ideal “School of Human Culture.”

(Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University)

In preparation for opening the school in September 1834, Alcott set about creating the optimal environment for learning. Bronson had recently written to Peabody that he found emblemsâhis word for what we would call “symbols”â“extremely attractive and instructive to children.” The modern age, he thought, had done education a grave disservice by stripping truth of its symbolic garments and making instruction “prosaic, literal, worldly.”

6

With these thoughts in mind, he created a schoolroom rich in symbolic associations. The four-story Masonic Temple that housed the school was something of a symbol in itself. Completed only two years earlier, the temple hosted concerts, symposia, and other cultural events. In the eyes of Bostonians, it represented their city's continuing place in the vanguard of America's artistic and intellectual progress. The interior space of the Temple School was cavernous by comparison with that of virtually any other elementary school of its time. The main room was twenty yards long, and the high ceiling supplied an apt visual emblem for Alcott's lofty ambitions. Sunlight streamed in through a large, ornate Gothic window, adding literal illumination to the figurative light that the teacher and his assistant daily cast on their young pupils.

As to furnishings and decorations, Alcott spared no expense. Carefully chosen busts of Plato, Socrates, Shakespeare, and Sir Walter Scott stood on pedestals in the four corners of the room. As the students worked at their lessons, a portrait of Dr. Channing looked benignly down on them. Paintings, maps, assorted statuary, and a copious library added still more splendor. Alcott himself sat at an elegant desk, ten feet in length. Knowing that conversation was to be the backbone of his instructional work, he had had the desk specially made in the shape of a crescent so that the children might be encouraged to sit in a semicircle in front of him, an arrangement favorable to verbal exchanges. Perched atop a tall bookshelf behind the instructor's chair was a larger-than-life bas-relief head of Jesus, positioned so that the instructor and the Savior were in the same line of sight. During a discussion of the Gospels, one of the young pupils told the schoolmaster, “I think you are a little like Jesus Christ.”

7

Was it the teacher's kindhearted wisdom or the face looming above his head that prompted the comparison?

Alcott's classroom was far from permissive. Indeed, Elizabeth Peabody went so far as to call him “autocratic.” However, Alcott was careful to give his authority the appearance of democratic sanction. The first day the school was in session, Alcott asked the children why they had come. “To learn,” came the obvious response. Ah, but to learn what? the schoolmaster pursued. This question was a bit harder, so Alcott slowed down. After a series of inquiries, the children agreed that they had come “to learn to feel rightly, to think rightly, and to act rightly.” They were there, Alcott implied, not so much to acquire facts as a reflective, useful state of mind. As the children came to this conclusion, Peabody wrote, “Every face was eager and interested.”

8

He also asked whether it might sometimes be necessary to punish them, and he did not proceed until the children admitted the reasonableness of this point. As a matter of both justice and personal honor, Alcott would not punish a child until the offender admitted the fairness of the punishment. During lessons, the children were strictly forbidden to talk among themselves. If this rule were breached by the slightest whisper, he would immediately stop the lesson and wait until order was restored. By pausing in this way, Alcott was, of course, taking time away from the good students as well, but he did this intentionally. He wanted to show everyone that moral transgression inevitably caused the good to suffer along with the bad, and he meant for the well-behaved children to realize that one must sometimes bear the burden of another's wrongs, in order to bring them around to a sense of right.

Alcott did not do away with all corporal punishment. Indeed, one visitor to the school expressed regret that Alcott still occasionally resorted to the ruler. However, Alcott inflicted pain only as a regretted last resort, and he always led the offender out of view of the other children to do so, to spare humiliation. Alcott's most remarkable innovation, however, involved a startling reversal of normal practices. One day, when two boys had disobeyed in an especially offensive manner, Alcott reached for his ruler and called the two forward. However, instead of administering the expected blows on the hands, he announced his belief that it was far more terrible to inflict pain than to receive it. He extended his own hand and ordered the boys to strike

him.

Peabody recorded that “a profound and deep stillness” then descended on the classroom. The two boys protested, but Alcott would not be moved. At last the boys obeyed, but they struck only very lightly. Not satisfied, Alcott demanded whether they thought they deserved no more punishment than that. The boys now struck harder, as Alcott stoically bore their blows. For the boys, however, the act was unbearable. As they brought the ruler down on Alcott's hand, they erupted into tears. A small moral revolution had occurred.

9

Curious intellectuals came to the school in a steady stream. The comfortable sofa that Alcott reserved for guests played host to Channing, Emerson, and a formidable Englishwoman named Harriet Martineau, who had come to the United States to write a book, later titled

Society in America.

Invited by Peabody to observe the school, Martineau was one of the few visitors who left unimpressed. She wrote acidly of Alcott, “The master presupposes his little pupils possessed of all truth; and that his business is to bring it out into expressionâ¦. Large exposures might be made of the mischief this gentleman is doing to his pupils by relaxing their bodies, pampering their imaginations, over-stimulating the consciences of some, and hardening those of others.”

10

Martineau's visit had two significant consequences. One was that Abba Alcott, perhaps sensing that Martineau would speak ill of her husband's school, fiercely confronted Peabody and berated her for inviting such a person. Abba's tirade, which was Peabody's first taste of Abba's infamous temper, marked the first rift in her association with the Alcotts. Secondly, Martineau brought back to England news of Alcott's work. The eventual consequences of this publicity were, for the Alcotts, both unexpected and enormously far-reaching.

Peabody, for her part, was elated by the students' progress in command of language and self-control. She secured Bronson's permission to keep a detailed journal of the school's proceedings, which she meant to publish as a testimony to his ideas and methods. Peabody confined her record principally to Alcott's lessons in language, in which the teacher transformed a spelling book into a treatise on practical ethics. “Look” gave rise to a discussion of inward reflections on the soul. “Veil” became a metaphor for the body's concealment of the spirit, and the world itself was presented as a veil for the mind of God. Pausing over the word “nook,” Alcott asked his scholars if they had any hidden places in their minds. When some answered that they did, he expressed sorrow, stating that a perfect mind had no need of secret places.

11

Leading them in this way, Alcott gave his students a rich understanding of the metaphoric power of language. On the subject of symbols and parables, he told Elizabeth Peabody, “I could not teach without [them]. My own mind would suffer, were it not fed upon ideas in this form, and spiritual instruction cannot be imparted so well by any other means.”

12

His future friend Emerson was soon to offer similar ideas in his great book

Nature,

which asserts that “the use of the outer creation [is] to give us language for the beings and changes of the inward creation. Every word which is used to express a moral or intellectual factâ¦is found to be borrowed from some material appearance.”

13

Not only did Alcott anticipate Emerson's doctrine by two years, but he made it comprehensible to young children.

During the early months of the Temple School's existence, in late October 1834, Bronson resumed his diaries on Anna and Louisa, now combining their experiences in a single record, “Observations on the Spiritual Nurture of My Children.” Writing for only four weeks, he created a 260-page manuscript. After a monthlong hiatus, Bronson then added another 300 pages of observations, begun in January 1835, which he titled “Researches on Childhood.” Bound together into a single volume, the two manuscripts combine factual impressions with speculations about the best ways to improve the children's behavior, supplemented as always by lengthy discourses on the nature of the human spirit. Never published, these observations are arguably Bronson's greatest achievement in documenting child development.