Edie (22 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

At a certain point I looked over at Edie, realizing that this was all going wrong. I didn’t have the courage and it didn’t occur to me, but I should have said: “Hey, Edie, let’s split. Edie, you don’t need to take this.” She was totally in the movie, she was like drawn up inside herself. She was right up there on the screen. Her eyes, big as they were, were bigger. Her hands were clutched around her knees. She was rigid.

Finally there’s that closing scene when the Professor returns to the college town, a total failure: he’s lost everything—his academic standing, his integrity, his money, and Dietrich is having an affair with this circus strongman, so he has

this

humiliation also laid on top of him. He comes out on the stage as the magician’s apprentice and he begins to flub his lines. He can no longer hold it all together. He’s supposed to call out “cock-a-doodle-do”; and the magician produces an egg from his ear. The camera doesn’t turn away: you see this sort of mottled, apoplectic face. Finally the magician, to get a laugh, breaks some eggs over his bald head so the yolk runs down his face. That snaps him completely and he starts to cry out “cock-a-doodle-do, cock-a-doodle-do,” and they come for him with the straitjacket and put him in his old schoolroom where he had once taught die boys. That’s how it ends.

Well, you can imagine what this did to Edie that night. The man carrying the straitjacket! It was a brutal movie; it is almost unforgivable to use a camera like that. When the Professor broke, it was so relentless the way the camera held on him. Next to me Edie said: “Please, God, end this scene,” but the camera just stayed there and hung on this man: insane, broken completely, sprung out of his head, crowing at the top of his voice while they threw bottles and things from the audience.

I didn’t dare look at Edie. There was nothing I could do. Maybe I should have held her hand and said: “It’s only a movie.” It was a heavy night for her.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Bobby was in the hospital in Hartford, Connecticut, when Minty died. I don’t know how he found out about it, but when he called me—he must have been sedated—he just said, “Poor Minty . . . poor guy.”

GEORGE PLIMPTON

Of all the family, Bobby was die only one who wasn’t at all consistent. He took on guises—like a chameleon. Minty was predictable. Bobby wasn’t. I remember Bobby when he got to Harvard from Groton twelve years earlier, in 1951. He was an astonishingly handsome kid then—I mean handsome in the sense that everybody, male or female, stared at him without really meaning to . . . not lasciviously, but because he

was

extraordinary to look at. He couldn’t get over it himself. He’s the only person I ever met who suffered a true narcissist complex: at that time he carried a small pocket mirror which he would take out and admire himself in without any self-consciousness, the way a beautiful woman wI’ll preen herself in a fashionable restaurant. Bobby carried the mirror to the beach at Hendaye down on the Basque coast, for God’s sake, and he would slip it out of his bathing suit and look at himself. I don’t remember that anyone kidded him about it, or even made slurring remarks behind his back—he was so guileless about it. Everything had to be in order. Every hair in place. A fashion plate. He was a terrific success with the

girls that summer, but it seems to me his whole attitude about them was quite perfunctory. I mean,

they

were the ones who appeared to do all the work.

He wore this curious grin. I used to think it was the grin of the cat who swallowed the canary. He seemed blessed with the best life can offer to someone who was just, what? twenty years old: extraordinary looks, a prestigious name, a wonderful and vibrant father (at least that’s what I thought), a mother my parents thought was the salt of the earth (with which I would have agreed), a huge number of healthy brothers and sisters, a great education (Groton and Harvard), fine if somewhat exuberant friends, a grace and charm that endeared him to older people, social acceptance (the Porcellian Club), and really with all this he had

everything

to look forward to. But then I realized that the grin was too fixed and strange to have any connection with stability. It was so vacuous. It was tacked on. I thought at the time that he was simply a bit victimized by his liberal education and patrician background—not quite knowing what to do with either . . . which was certainly a common enough phenomenon. Certainly I thought if there were any problems he could straighten them out.

SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG

In Bobby’s undergraduate days at Harvard I had an office off the library In the Fogg Museum, where I was a professor in the Fine Arts Department. It was immediately accessible to anyone who wanted to walk in the door. Bobby did so frequently. He would sit himself down and open up a subject of discussion which might or might not be relevant, and then he would very rapidly wander off into philosophical generalizations of perfectly extraordinary breadth and confusion. It was almost impossible to get him to think in a consecutive and disciplined way. But he would insist on bringing up the heavy artillery, involving himself with first principles at the philosophical level. He really was terribly intelligent. One felt that his intellectual derailments were the consequence of psychological motives, not of any defect of mind. Sometimes he would say things that had the most extraordinary acuity, really great intellectual penetration, but he himself was never accessible to his own critical faculties.

Often he brought up his father, characterizing him in a way which I can only describe as pathologically hostile—a relationship dominated by buckets of incompatibility. Duke couldn’t see at all what Bobby was about; terribly impatient with him. And Bobby, on his side, was absolutely hostile to his father’s insistence upon stringent fiats and all the virtues that Bobby thought were Boy Scoutish.

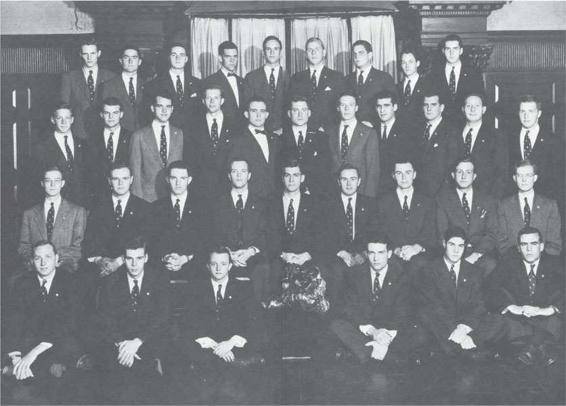

The Porcellian Club, Harvard, 1953. Bobby is in the back row, fourth from left.

WILLIAM ALFRED

The odd thing was that, despite Bobby’s obvious difficulties with his father, he carried his father’s nickname, Duke, through college. He was a very strange young man. He had these fits of irascibility and actual weirdness. His freshman advisor gave him to me and said, “See if you can’t get this guy through his sophomore year.” He was taking Fine Arts at the time, and I offered to tutor him. Just before Christmas, 1952, he handed in a paper which didn’t make any sense to me. 1 said, “Read it to me sentence by sentence and then tell me what they mean.” We talked it over; it was like giving dictation. After a while he began to get the hang of it. He could write by himself then. But after Christmas vacation at home he just gave up. I was told that his father said things like “You’re sort of stupid. You’re just a good-looking Airedale. I don’t think you can use your brains. Your only hope in life is to marry some rich girl.”

“I can’t do any more work,” Bobby told me. “I’ve got these terrible pains in my knees.” He had taken up so much of my time that my first reaction was to take a book and hit him on the top of the head, he made me so damned mad. He told me, “Every time I go home I get the stuffing kicked out of me, and I just don’t see what’s the use. I’m going to let everything slide. I just don’t care whether I pass or not.” I’d never seen anybody collapse that fast. Whatever happened out there must have been awful.

THOMAS J. MCGREEVY

Part of what probably finally set Bobby off was the end of his romance with Randy Redfield. The Redfields were part of the aristocracy of Harbor Beach, Michigan, if you can imagine such a thing. Bobby met her when she was at Radcliffe. They went together for two or three years. She was an Ail-American sort of beauty—dark-haired, dark-eyed, big-boned, with a very expressive face. She’s now the Countess of Toulouse-Lautrec and lives in Versailles and she is very involved with horses. I think the break-up with her had a considerable effect on Bobby.

RANDY REDFIELD

He was having terrible emotional problems. His nickname, Duke, seemed such a totally inappropriate nickname for somebody who was so lost and confused . . . pitiful. He would talk long and hard about the most trivial, mundane things—not quite how-to-get-up-in-the-morning, but almost. He would burst into tears on my shoulder. I think he loved being with me because I listened to him. I like underdogs; I felt very concerned for him. You can’t really close

a door on someone like that. He was preoccupied with the idea of destroying himself: “If s not worth it. I can’t hack it. I would be better off dead. We would all be better off. Serve Father right !”

He was obviously very frightened of his father, and impressed by him at the same time. His father had been commissioned to make an equestrian statue, his first commission in years . . . oh, just a glorious thing, but very frightening for Bobby, because it somehow confirmed a facet of his father’s strength.

Mr. Sedgwick disapproved of me. I represented a magnet. He did not tolerate any kind of magnetic field other than his own. And besides he considered the Sedgwicks socially superior to my family . . . socially and culturally . . . because we were from Harbor Beach, Michigan. He laid down the law that Bobby was not to be in touch with me. We’d have these clandestine telephone calls. Bobby would say: “I’m hidden in a phone booth. I love you.” We’d arrange to meet. He’d talk endlessly . . . endlessly. The domineering father would come through, of course. I have absolutely not a single recollection of Bobby talking about his mother. Not one! Nor what he did as a child . . . the nursery rhymes, the songs he learned—none of that came through. It was very much a house draped in black.

ALEXANDER SEDGWICK

Bobby and I both lived in Eliot House his sophomore year at Harvard. That spring he had a breakdown. I was in my room and suddenly I heard a ruckus in the hall. Someone was screaming. I came out to see what was going on, and there was Bobby being taken away in a strait jacket to the hospital.

JUDITH WATKINS

When Bobby came back to Harvard in the fall of 1953 after that breakdown, he saw a lot of me. There were a lot of people at war inside Bobby. Fascinating, beautiful, spoiled, lost, and self-destructive. He was a searching person who turned to far eastern philosophy. He was thinking of doing what Jay Rockefeller had done: go to Japan and live, go deeply into Zen. He got a kind of tranquility from studying Chinese; it seemed to relax him a lot. But then he would slip out and drive all night to New York and go to the Copacabana.

PETER SOURIAN

He was seeing a psychiatrist in Boston, who kept sending him little notes on slips of paper: “Bob, you are doing better, just hang in there.” They were like little cheerleader notes.

Into this situation—I was sharing a suite at Eliot House with Bob

—came Gregory Corso, the poet. He was also in mental pain. Bob was around being depressed and lumbering. He sometimes got rather heavy, an athletic sort of heavy rather than fat, so that when he and Gregory went out for walks, it was like watching a big whale and a pilot fish. It brought out the best in Gregory—which was his gentle side. Bob once said to me, “You know, he soothes me.”

Corso had come up from Greenwich Village. He stayed with us there in our suite, which was not generally done. I had two foam-rubber mattresses and dyed sheets and metal poles, out of which I made a kind of elaborate Arab-like tent. That’s where Gregory ended up sleeping—in a sort of house within a house. He would write in there during the day.

Sometimes we brought him into the dining room of Eliot House, but usually we smuggled his food back to the room in bowls. He was, well . . . a bit

difficult

in the dining room. He would attack people—I don’t mean physically, of course—for being idiots. He had a confrontation with Archibald MacLeish, who was the Master of Eliot House that year. “You’re not a poet,” Corso growled. MacLeish rather graciously put up with all this.

Then that relationship with Bob began. There was some sort of affinity, the poet with the madman. I hate to say madman because I don’t mean that. I mean, after all, poets are healers of a kind. There’s sort of a psychic nerve they’re touching.

GREGORY CORSO

I loved Bobby . . . not homosexually, but friendship. Nothing else, no. He was a very moody person. Very moody. And stuck on Zen Buddhism, which was the thing that helped cool him. He was the first person I ever saw get into Zen . . . outside of Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder doing that number out in San Francisco.

I had come out of prison. Out of Dannemora. For what? For nothing. A simple robbery. I was there for three years. Good God, those prison years were the

best.

If I’d gone to high school, I’d’ve been in there with kids; I wouldn’t’ve learned a thing. But in prison I got an education from the old men on Death Bow. Spoke to those people! Man, they knew the books. Stendhal’s

The Red and the Black,

Kierkegaard, Hegel. Ate up books like mad. That was the best!