Edie (49 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Edie and Viva on a raft during the orgy scene from

Ciao! Manhattan

GENEVIEVE CHARBIN

Before he went to jail, it was Paul America who took a hand with Edie. Paul had been on heroin, but he had gotten off of it, and, as it turned out, he took up residence with Edie in the Chelsea And He Got

her

off it as well. He was very firm with her.

He’s a fascinating person. Quite a handful. He was almost too dangerous and mind-blowing to ever let him out of sight for a second. Can’t get bored with

him.

His psychic balance is very delicate—like Edie’s, but

very

delicate. You could almost say—though he comes from where, God knows, New Jersey?—that he had just landed from another planet. Almost a total telepath, I would say—you cannot tell him a lie. You can’t even begin to open your mouth to tell a lie . . . because this look that comes into his eyes is like that of an intelligent child’s eyes.

But if he got overdoses from people, he’d go over the brink. He wanted to do violent things or kI’ll because of it. You never knew if the next moment he wasn’t going to leap on you and cut your throat. Once he arrived at my door and pulled out a giant plumber’s wrench, a really big wrench, from under his raincoat. He held it up raised over my head. But that’s as far as he went. He was looking for money. I let him ransack the drawers. He found some checks left over from an old account riffling through them. I said, “What are you going to do with those? They’re no good.” He said, “Oh, never mind.” He huffed out, taking a radio with him.

He would have to leave town when he got violent and end up in some sort of commune. Then he would come back to New York high-spirited and with the strength of a god. Incredible. Then he’d give you more devastating looks than ever. Crazy again. The cycle kept repeating itself.

Edie had her relationship with him when he’d just returned from the country: he was healthy, strong, and gentle. Lovely. He got her off heroin by keeping her busy. Their relationship was really nice for a while. Then it got ticklish because after a month in the city Paul gets to be unbearable, paranoid, insane . . .and so they finally split up. But while it was going, it was terrific. Edie was in seventh heaven with him.

PAUL AMERICA

Sometimes Edie and I had money for speed and sometimes we didn’t, so sometimes we would buy it and sometimes we would just take it. Often we went to Brooklyn to pick up the speed at this dude’s home we called the Captain. He had a stI’ll set up in his apartment to make speed. The batches were different and some of it

was probably dangerous to take. So he would have people try it. The kids hung around. We tried most all of them. The Captain dried the stuff over the oven after it had condensed. Most of it came out brown or yellow. The good stuff was normally white. It wasn’t no problem because we were already high on some good stuff, and the rest of it would go through us. Edie was into that. Most of the time people who haven’t been doing a lot of it wI’ll be a little reluctant to take anything. But Edie was right there. She didn’t care.

One of Edie’s sisters and her husband came one night to the Chelsea and stayed for a little while. We smoked some marijuana and had some drinks. They said, “We don’t think you should live here. We want you to come back home.” We gave them all the reasons why she should live there. When the dude left, he said, Take good care of her, man.”

We had some good times. We would go to the Park and have a picnic. Or lock the doors to be sure no one was coming into the hotel. But those times never lasted very long. Somebody was always coming over.

I threw a lot of people out who were bothering her . . . who had come to rip her off. I threw them out as soon as they came in. She didn’t dig that, because she dug the scene of a lot of people. She called the bellman and tried to have me thrown out. So I left and didn’t come back.

DANNY FIELDS

It was a marathon over at her place, just taking a lot of speed and sitting there for a couple of days. Edie was into making little things—stringing beads and pasting things down.

Leonard Cohen, the poet, was living down the hall. I thought it would be nice if he met Edie. He was into incense and candles, and he did a lot of reading which he got from the magic witchcraft place on Twenty-third Street on how candles should be arranged—the whole Buddhist mystical concept. He burned a lot of incense. The Chelsea didn’t like it much; they were always trying to throw him out. He used this smoky kind of stuff which floated down to the lobby, and they were always calling the fire engines.

I took him down the hall to meet Edie. Zoë, her friend, had fallen asleep on the floor. The speed had given out and she’d collapsed on this tube of glue, which had sprung open under her, and she’d become glued to Edie’s floor. Every time she’d turn over in her sleep, her shirt would stick. Edie was on the phone. She had a cat with her, Bob Dylan’s cat’s son. Smoke, his name was. So I brought Leonard Cohen into this scene. What was interesting to him was this line-up of candles Edie had on the mantelpiece. He was troubled when he

looked at them. He said to me, “I don’t know if you should tell her this, or if I should, but those candles are arranged in such a way so they’re casting a bad spell. Fire and destruction. She shouldn’t fool around with these things, because they’re meaningful.” It was very complex. It had to be someone who had really been into candle-arranging and voodoo Haitian candle numbers to figure it out. But when Leonard told Edie, she said she didn’t want to hear about such things, that was silly, they were just candles. That was ironic, wasn’t it? I mean, her life was full of warnings, probably. It was very soon after that the apartment caught fire and die cat was lost.

DAVID WEISMAN

Edie was nude, covered by a blanket, lying on the floor of die lobby. no one would touch her. People running in and out. It was such an insane night. I took her right down to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where they wouldn’t admit her. they said her burns weren’t sufficient. Dr. Roberts was called; he was out in the Hamptons. he came in at seven o’clock in the morning and gave her some first aid and some injections. her burns weren’t as bad as what happened to the Chelsea . . .

BOBBY ANDERSEN

Her description of the fire was terrifying . . . how she’d awakened and the entire room was in full blaze. I believe it because I went to the hotel to rummage through die ashes to see if there was anything salvageable, and were was nothing left. Where the bed had been was a hole where it had burned through to die floor below. she had obviously been asleep in her bed and had set fire either to her bed or the rug and eventually it had all burned right through. she got up and tried to get die lock open, but she gave up and hid in die closet. When die smoke got into die closet, she took another try at it and burned her hands on die knobs, which were white heat, and then she collapsed outside in the hall.

PAUL AMERICA

Edie told me that she was trying to bake a sweet Potato and die oven exploded.

GREGORY CORSO

She did not die in the fire. The cat died in it. the cat was named Smoke, and he went up in smoke.

EDIE SEDGWICK

(from

Ondine and Edie) The second fire, they wouldn’t come near me. They would not. I went into the lobby at the

Chelsea. They said, “Wait until the ambulance.” They gave me an oxygen tent. I had bruises across the scalp. We started to St. Vincent’s, where my brother Bobby died.

ROBERT MARGOULEFF

After She Came Out Of The Hospital, She Had Nowhere To Live, Right? Her parents had cut her off; the movie had taken every penny I had. I finally put her up in my apartment on East Fifth Street. The place always smelled of italian cooking from the neighbors downstairs. There was never too much hot water, and always a stream of people. I had to get someone from the East Village community who would take care of her and go on trips with her and be a sort of companion. I couldn’t do it myself. I was out all the time trying to keep the

Ciao!Manhattan

zoo parade going. I got somebody by the name of Bobby Andersen.

BOBBY ANDERSEN

I met Margouleff just after I got out of the hospital, where I was seriously I’ll with hepatitis and told every day that I wasn’t going to make it and was all prepared to die. I came out all traumatized. Very strange. Margouleff came along. I was so weak already from exhaustion I was ready to fall down in the street. I had lost my apartment and everything in it. He walked up to me and he said, “Hello, you big tomato.” I said, “Get the hell out of here. Leave me alone, you creep.”

He could see that I was not feeling well and he took me home to his apartment. I never left. I stayed there for three and a half years. When I met Margouleff, he was importing Hercules movies and dubbing them in English at ABC City. When he said that he was going to make an above-ground underground film, we all made a lot of faces and everything. He said someone called Edie Sedgwick was going to star in it. I’d never heard of her. I envisioned this blonde, pigtailed, freckle-faced, homely, wire-rim-glasses type from the name: Edie Sedgwick. It didn’t sound very glamorous or pretty.

You should have heard the way Margouleff carried on about her! He hated Edie. He couldn’t compete with her. She was so erratic, at least as far as he was concerned. He couldn’t understand that anyone could get that high on drugs. . . . he never had even a drink. And here were all these people around him with needles in their asses and everything, shooting amphetamine. I don’t think he understood all that vibrancy, all that stimulation that the drugs get going in them.

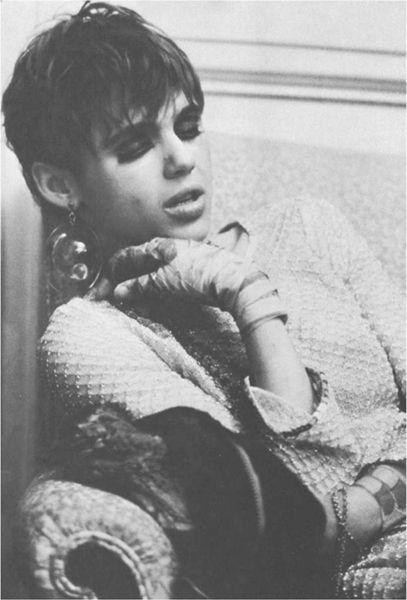

Edie after the Chelsea Hotel fire

That was how I got involved. Apparently Edie wasn’t showing up; they couldn’t get her to learn lines, or do this or that. She had been burned in the Chelsea fire, but no one wanted to take care of her. Everyone had refused. So Margouleff asked me if I wanted a job that paid twenty-five dollars a day to make sure that she got up in the morning, had her face washed, and turned up at the studio in proper attire and behaved herself.

I said, “Sure!” I figured I’d be a real male nurse and real nasty.

Margouleffs was a very strange apartment. He owned it and paid the rent. After that it was my apartment. Every room was different: a psychedelic room, a Victorian room, a Georgian room. The kitchen was the best. It had a tin ceiling. The walls were painted as an American flag. I spent a month’s work on the refrigerator to make it look like a Coke vending machine.

Margouleff used to tell everybody that I was his houseboy, which I thought was very insulting. I fixed the apartment up; I decorated it; I ran it. It was in the East Village, a fabulous ramshackle six-room railroad flat, and one day I walked in and looked down to the end, where sitting at the harpsichord was this breathtaking blonde that I could see from six rooms away . . . frosted blonde. I walked over. She stood and asked, “Who are you?” I said, “I’m Bobby. I live here. Who are you?” She said, Tm Edie Sedgwick. Are you my nurse?”

She had these two people with her, one a boy named Anthony Ampule and a friend of his named Donald, who was a professor. On the harpsichord they had this big pile of methedrine, which they were scooping up and mixing into water. Anthony Ampule was called that because he was able to get ampules of liquid amphetamine from his doctor. I don’t know what his real name is; even today he’s called Anthony Ampule. They were standing there at the harpsichord measuring out their methedrine. I looked at Edie and I said to myself, “Well, how

fabulous!

This fabulous creature!” She was so

electric . .

. just wonderful; I decided about four minutes after I knew her that she was not an Edie, she was an Edith.

She didn’t go out that night. She hadn’t brought much of anything with her. She had these great big baseball mitts for hands because of the Chelsea fire, all covered with gauze and bandages. I went out to Max’s Kansas City and brought back some food for her. Double shrimp cocktail. A chocolate malted, which they made only for her there.

Mickey Ruskin, the owner, would go in the back and melt the ice cream and beat it and make her a chocolate milkshake.

That was how I met her. I was so pleased. I just thought she was wondrous instantly. So I wasn’t a hideous male nurse at all. We caught on like wildfire and got along so well it was wonderful. At Max’s they used to call me Edie’s nurse, but I didn’t mind. We’d have drinks there and put it on Margouleffs account. Terrible! Those were the days of signing for everything on anybody’s name. Everybody was very rude about it.