Edsel (31 page)

“I put away enough to keep me for a couple of years, provided I move out of this place and into an apartment. After that, I don’t know. An old friend of mine owns a gardening supply store in Troy. Maybe he can use a first-class salesman.”

“I’m sorry, Connie.”

I moved a shoulder. “The severance pay was good. The hard part will be living down the fact that I had the Edsel account. I don’t think it will go on my résumé.”

“I’m sorry about that, too, but I meant Agnes. I heard she left.”

I wondered from whom. It was a small town for its size. “She wanted someone who could give her signposts along the way. I can’t blame her for that.”

While we were talking, a red Corsair driven by a man my age in a corduroy coat and a season-rushing cocoa straw hat with a yellow band boated around the corner and blasted its horns at sight of the Citation. He waved derisively. Someone had jammed a white plastic toilet seat onto the red car’s horse-collar grille.

There wasn’t much more to say. Janet and I wished each other good luck, promised to write while the post office was still forwarding our mail, and she put the big car in gear and swung into the street and away on a cushion of bubbling exhaust. Of course I never heard from her again.

There isn’t much more to say here, either, except it was a tragedy what happened to the Edsel. Sales picked up briskly in October 1957, then began to lose steam just when everyone thought the car was in the clear. In December Henry Ford II came on closed-circuit television to pep-talk wavering dealers. Shortly thereafter, Ford began jettisoning personnel to lighten the burden, changed advertising agencies, and replaced the entire division promotional staff. My successor was a business-school graduate exactly half my age who had worked on the “Be Happy, Go Lucky” cigarette campaign. Ford shook my hand warmly and told me to go on driving the Citation until I found a replacement. “We can use the advertising.”

The top-of-the-line Citation and the second-from-the-bottom Pacer disappeared with the 1959 model year. The grille was made less noticeable and a number of mechanical improvements were engineered to satisfy

Consumer Reports

, who sniffed at all the gadgetry and complained about the steering and suspension. But by July 1, 1959, only 84,000 units had been sold, a significant number of which were raffled off at church bazaars and school carnivals, causing people to ask of new Edsel owners: “Where did you win yours?” The joke went into the bin with all the rest, including variations on the comment that the car looked like an Oldsmobile sucking on a lemon.

But it might have survived the jokes; and in fact the 1960 Edsel Ranger, minus the hilarious grille and unpopular pushbutton gearshift and with a more manageable wheelbase, won the admiration of most critics, for both its performance and its realistic price. But by then Ford was just selling out its inventory. The Edsel died, aged twenty-six months.

The fifties died about the same time. Dwight D. Eisenhower was on his way out, having lost his characteristic mongoloid grin and most of his sense of humor in a blow-up with Nikita Khrushchev that promised to prolong the Cold War another generation at least. The Democratic Party, dormant for eight years, was talking of running the bootlegger Joe Kennedy’s son for President, the United Nations was pressing Washington for a show of solidarity in Indochina, preferably with men and material, and Vice-President Nixon was preening himself for a run at the Oval Office. Batista was out in Cuba, Fidel Castro was in. On a more local level, the Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, chaired by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas, had turned up sufficient heat under the American Steelhaulers Union to bring national president Albert Brock to the serious attention of the Justice Department. Chief counsel to the committee was a young Washington attorney named Robert Kennedy, another son of the bootlegger. Assisting him in Detroit was Stuart Leadbeater, in private practice after having resigned from the city attorney’s office to run unsuccessfully for county prosecutor, and reborn as a Democrat. Both men would continue to be festering thorns in Brock’s side throughout the rest of his tenure. It seemed I could bring that man nothing but grief, even when I wasn’t trying to help him.

The new era was already assuming a shape completely foreign to the ten years that preceded it. What the next generation would think about those years would be based entirely upon the evidence of warped gray Kinescopes, overripe theatrical epics, a stack of 45-rpm records, and a handful of books. But the whole added up to so much more than just the sum of its parts. It was braggadocio and hope, fear and comfort, bad taste and good intentions, innocence and cynicism—Little Richard and Eleanor Roosevelt, tucked as securely as a lace valentine between the glossy four-color pages of a magazine. It was the most important time of our century.

On Labor Day 1959 I was standing in a crowd gathered in Grand Circus Park when Walter Reuther swept through behind a flying wedge of bodyguards on his way to the podium. He had on a light topcoat against the gray mist and a black felt hat with the brim pulled low on his forehead. Our eyes met when he came past, but only for an instant, and there was no recognition on his side. As I’d predicted he had continued to put on weight, and there was more of the bulldog in his heavy-jowled face than the terrier who had nipped at the heels of Big Auto until it was forced to acknowledge him, first with fists, then with contracts. I have no memory of what he talked about that day. I was distracted by the realization that there are men who can in a moment subvert your life to their own agenda, and in the next forget you ever existed. To this day, whenever I hear a news report of a hit and run, I picture Walter Reuther at the wheel.

The Ford Motor Company lost three hundred fifty million dollars on the Edsel. Its stock fell twenty dollars per share from an all-time high recorded during the first years of Henry II’s leadership. Why the venture toppled depended on where you were standing when it began to teeter. Some said it was a bad car, but they were only repeating the opinions of others who never drove one or even sat in one. The recession, our first since the uncertain days immediately following the end of the Second World War, is an easy target; or if your preference runs to the obvious you can blame the strange grille. Most likely it was the human factor that brought it down, the petulant backbiting at the senior executive level that inspired company president Robert McNamara, six days before the Edsel was unveiled, to confide to a companion: “I’ve got plans for phasing it out.”

What difference does it make why? It was a good car, and they killed it. They being us. But like the Oscar Wilde hero, when we plunged the dagger through the physical embodiment of our collective soul, we pierced our own collective heart as well. The first failure is always entertaining. After that they become commonplace, even expected. Success becomes the diversion.

And so the whole damn dizzy decade was an Edsel.

Loren D. Estleman (b. 1952) is the award-winning author of over sixty-five novels, including mysteries and westerns.

Raised in a Michigan farmhouse constructed in 1867, Estleman submitted his first story for publication at the age of fifteen and accumulated 160 rejection letters over the next eight years. Once

The Oklahoma Punk

was published in 1976, success came quickly, allowing him to quit his day job in 1980 and become a fulltime writer.

Estleman’s most enduring character, Amos Walker, made his first appearance in 1980’s

Motor City Blue

, and the hardboiled Detroit private eye has been featured in twenty novels since. The fifth Amos Walker novel,

Sugartown

, won the Private Eye Writers of America’s Shamus Award for best hardcover novel of 1985. Estleman’s most recent Walker novel is

Infernal Angels

.

Estleman has also won praise for his adventure novels set in the Old West. In 1980,

The High Rocks

was nominated for a National Book Award, and since then Estleman has featured its hero, Deputy U.S. Marshal Page Murdock, in seven more novels, most recently 2010’s

The Book of Murdock

. Estleman has received awards for many of his standalone westerns, receiving recognition for both his attention to historical detail and the elements of suspense that follow from his background as a mystery author.

Journey of the Dead

, a story of the man who murdered Billy the Kid, won a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America, and a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In 1993 Estleman married Deborah Morgan, a fellow mystery author. He lives and works in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

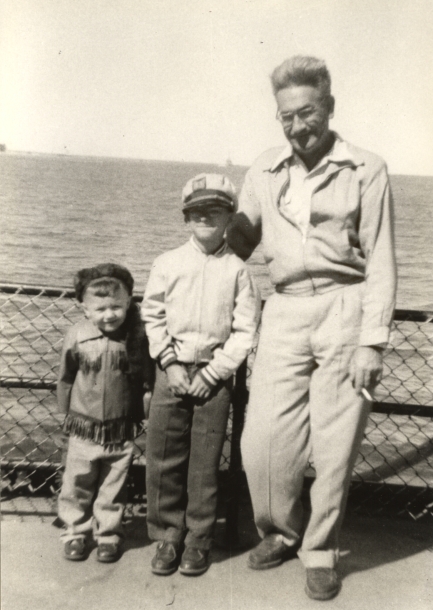

Loren D. Estleman in a Davy Crockett ensemble at age three aboard the Straits of Mackinac ferry with his brother, Charles, and father, Leauvett.

Estleman at age five in his kindergarten photograph. He grew up in Dexter, Michigan.

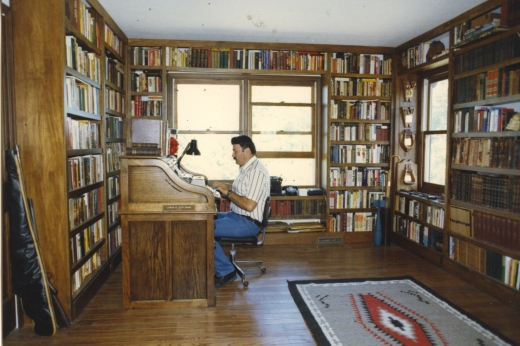

Estleman in his study in Whitmore Lake, Michigan, in the 1980s. The author wrote more than forty books on the manual typewriter he is working on in this image.

Estleman and his family. From left to right: older brother, Charles; mother, Louise; father, Leauvett; and Loren.

Estleman and Deborah Morgan at their wedding in Springdale, Arkansas, on June 19, 1993.