Eight Little Piggies (39 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

When we turn to skull widths, however, we note variation where lengths showed constancy: Puppies differ from adult foxes of the same size; puppies also turn into dogs of greatly altered shape, and small foxes are easily distinguished from large wolves by proportions of width elements. The material available to dog breeders should be extensive.

Wayne finds that dog breeds do vary greatly in width elements. (We might be tempted to say, “So what; doesn’t everyone know this from a lifetime of casual inspection?” Yet our intuitions are often faulty. Wayne shows that small, snubnosed breeds have wide faces, not short skulls or jaws. Readers might be chuckling and saying, what’s the difference—doesn’t overwide amount to the same thing as undershort, as in the fat man’s riposte that he is only too short for his weight? But the statements are not equivalent, for we are comparing lengths and widths with a common standard of body size. Small breeds are the right length, but unusually wide, for their size.) The great variation among dog breeds is not uniform among all parts, but concentrated in those features that supply raw material in growth and evolutionary history. Dog breeds form along permitted paths of available variation.

This study of internal potential helps us to predict which features will form the basis for variety among breeds (not simply what the selector wishes, but what the selectee can provide). But we can extend this insight much further to encompass the great differences in variety among domesticated species. If some features of dogs differ more among breeds because internal factors must supply the requisite variation, then perhaps, by extension, some entire species develop more diversity, not because human selectors have been more assiduous or because human needs require such variety, but because the internal facets of Galton’s polyhedron are many, closely spaced, and varied.

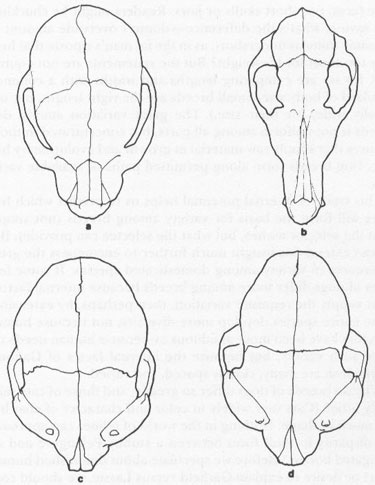

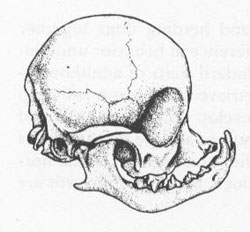

Why do breeds of dogs differ so greatly, and those of cats relatively little? (Cats vary widely in color and character of coat but not much in shape. Nothing in the world of felines can approach the disparity in skull form between a stubby Pekingese and an elongated borzoi.) Before we speculate about diminished human effort or desire to explain Garfield versus Lassie, we should consider the more fundamental fact that available variation in the ontogeny and interspecific scaling among cats offers very little for breeders to select. Lions differ from tabbies far less than large from small dogs while, more importantly, kittens grow to adult cats with only a fraction of the change in shape that accompanies the transformation of puppy to grown dog. Consider the accompanying figure taken from Wayne’s article and comparing, at the same size, neonates and adults of cats and dogs. Dogs have contributed to their own flexibility; cats, as ever, are recalcitrant.

Wayne makes a persuasive case that comparative diversity among domesticated species depends more upon available variation in the growth of wild ancestors than in the extent of human efforts. Horses change relatively little in shape during growth, and the heads of Shetland ponies do not differ much from those of the largest workhorses. Pigs, on the other hand, are second only to dogs in diversity of breeds. They are also unmatched among farm animals for marked change of shape during growth.

Skulls of dogs (upper row) and cats (lower row) show the differences between neonates (left) and adult animals (right). Note the much greater range of change in dogs vs. cats. Evolution

40 (2), 1986

.

Amounts of intrinsic variation therefore set limits and supply possibilities to breeders. But even the most variable of wild species do not become putty in the hands of breeders. Pigs and dogs vary in definite ways during their growth, and only certain shapes are available for selection at definite sizes. Wayne’s most persuasive case for internal limits lies in his demonstration that sets of traits in a standard “ontogenetic trajectory” (a sequence of stages from puppy to adult) tend to hang together. Dog breeds are not a hodgepodge of isolated traits, each taken at will from any stage of ontogeny. Traits of juvenility remain associated, and many breeds, particularly among small dogs, continue to look like puppies when adult—an evolutionary process called

paedomorphosis

(child-shaped) or

neoteny

(literally, “holding on to youth”).

Wayne has shown that—without exception—adults of small breeds resemble the juvenile stages of large dogs more than the adults of other wild canid species (small foxes)—a convincing demonstration that inherited patterns of growth set possibilities of change. Dogs resolutely stick to their own trajectories of growth. “To some extent,” Wayne concludes, “many dog breeds represent morphological snapshots between these developmental endpoints…. This suggests that small domestic dogs differ from foxes because puppies of small dogs cannot grow out of their distinctive neonate morphology.”

We know, of course, that breeders can do many wonderful and peculiar things, from making a dachshund into a frankfurter to turning a chihuahua into a hairless rat or a sheepdog into a woolly mimic of its charges. But these peculiarities are imposed upon a basic and unaltered pattern set by constraints of inherited growth. The trajectory of ontogeny provides, as Raymond Coppinger states, a “rough first draft” for all breeds.

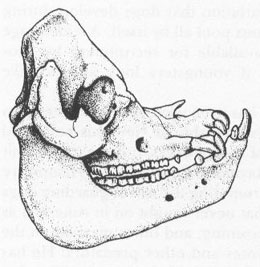

If ordinary variation in growth provides the main source for breeders, then a wild species’ own juvenile stages are the primary storehouse of available change. Under this basic theme of limits, we may understand an old and otherwise puzzling observation about domesticated versus wild species. Over and over again, we note that domestic species develop more juvenile proportions than their wild ancestors. We cannot explain this difference by smaller size (since domestic breeds are often larger than their ancestors) or by conscious selection on the old theme of planned optimality, for what possible common adaptive advantage could have inspired breeders to produce such a similarly shortened face in Middle white pigs, the Niatu oxen of South America, and the Pekingese of the Chinese imperial court (see figure). The only sensible coordinating theme behind these similarities is retention by neoteny of juvenile traits common to most vertebrates.

If these shared neotenous traits of domesticated species are not products of direct selection by breeders, then what is the common basis of their origin? Most experts argue that these juvenile traits are spinoffs from the true object of selection—tame and playful behavior itself. Organisms may vary as much in rates of development as in form. By breeding only those animals that retain the favored juvenile traits of pliant and flexible behavior past the point of sexual maturity, humans hasten the process of domestication itself. Since traits are locked together in development, not infinitely dissociable as hopes for optimality require, selection for desired juvenile behavior brings features of juvenile morphology along for the ride. (We may, in some cases, also select juvenile morphology for its aesthetic appeal—large eyes and rounded craniums, for example—and obtain valuable spinoffs in behavior). In short, these common juvenile features are facets of Galton’s polyhedron—correlated consequences of selection for something else—not direct objects of human desire.

This theme of correlated consequences brings me to a final point. We have explored the role of developmental constraint in shaping many features of dogs—their difference in diversity from other domesticated species; the disparate contributions made by various parts of their bodies to the unparalleled variety among breeds; the restricted sources of variation for construction of breeds, particularly the limits imposed by tendencies for traits to “hang together” during growth.

Neotenically shortened faces of domesticated animals. From top to bottom: pig, ox, and Pekingese dog.

Courtesy of The Natural History Museum, London

.

We might view these themes in a pessimistic light—as a brake upon the power of selection to build with all the freedom of a human sculptor. But I suggest a more positive reading. Constraints of development embody the twin and not-so-contradictory themes of limits and opportunities. Constraints do preclude certain fancies, but they also supply an enormous pool of available potential for future change. So what if the pool has borders; the water inside is deep and inviting. The pessimist might view correlated characters in growth as a sad foreclosure of certain combinations. But an optimist might emphasize the power for rapid change provided by the possibility of recruiting so many features at once. The great variation that dogs develop during their growth builds an enormous pool all by itself. A wide range of juvenile stages becomes available for recruitment by neoteny—a potential precluded if youngsters look and act like adults.

This great pool of potential has been used over and over again by breeders of domestic dogs. We should view this restricted variation as the main source of their success, not the tragic limit to their hopes. My colleague Raymond Coppinger, of Hampshire College, has spent ten years promoting the use of guarding dogs (a great European tradition that never caught on in America) as an alternative to shooting, poisoning, and other mayhem in the protection of sheep from coyotes and other predators. He has placed more than five hundred dogs with farmers in thirty-five states. Coppinger notes the great, and usually unappreciated, difference between guarding and herding breeds. Herders control the movement of sheep by using predatory behaviors of adult dogs—stalking, chasing, biting, and barking—but inhibiting the final outcome. These breeds feature adult traits of form and behavior; they display no neotenous characteristics.

Guard dogs, on the other hand, simply move with and among the flock. They work alone and do not control the flock’s motion. They afford protection primarily by their size, for few coyotes will attack a flock accompanied by a one-hundred-pound dog. They behave toward sheep as puppies do towards other dogs—licking the sheep’s face as a puppy might in asking for food, chasing and biting with the playfulness of young dogs, even mounting sheep as young dogs mount each other in sexual play and rehearsal. This neotenous behavior accompanies a persistently juvenile morphology, as these dogs grow short faces, big eyes, and floppy ears.