Eight Little Piggies (42 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Evolution is strongly constrained by the conservative nature of embryological programs. Nothing in biology is more wondrously complex than the production of an adult vertebrate from a single fertilized ovum. Nothing much can be changed very radically without discombobulating the embryo. The intermediate rate of change in lens proteins of a blind rodent—a tempo so neatly between the maximal pace for neutral change and the much slower alteration of functioning parts—may point to a feature that has lost its own direct utility but must still form as a prerequisite to later, and functional, features in embryology.

Our world works on different levels, but we are conceptually chained to our own surroundings, however parochial the view. We are organisms and tend to see the world of selection and adaptation as expressed in the good design of wings, legs, and brains. But randomness may predominate in the world of genes—and we might interpret the universe very differently if our primary vantage point resided at this lower level. We might then see a world of largely independent items, drifting in and out by the luck of the draw—but with little islands dotted about here and there, where selection reins in tempo and embryology ties things together. What, then, is the different order of a world still larger than ourselves? If we missed the different world of genic neutrality because we are too big, then what are we not seeing because we are too small? We are like genes in some larger world of change among species in the vastness of geological time. What are we missing in trying to read this world by the inappropriate scale of our small bodies and minuscule lifetimes?

DISCOVERY

, like its soul mate love, is a many-splendored thing. Stumbling serendipity surrounds some great finds—like

Archaeopteryx

, the first bird, unearthed by a quarryman at Solnhofen. Others are the product of dogged purpose. Consider Eugène Dubois who, as a Dutch army surgeon, posted himself to Indonesia because he felt sure that human ancestors must have inhabited East Asia (see Essay 8). There he found, in 1893, the first human fossils of a species older than our own—the Trinil femur and skull cap of

Homo erectus

(“Java man” of the old texts).

The most beautiful specimens in my office, which I happily share with about 50,000 fossil arthropods, rest in the last cabinet of the farthest corner. They are head shields of

Eurypterus fischeri

, a large, extinct freshwater arthropod related to horseshoe crabs. These exquisite fossils are preserved as brown films of chitin, set off like an old rotogravure against a surrounding sediment so fine in grain that the background becomes a uniform sheet of gray (see figure). They were collected in Estonia by William Patten, a professor of biology at Dartmouth.

When I first came to Harvard twenty years ago, I made a reconnaissance of all our 15,000 drawers of fossils—an adventure surely surpassing anything ever achieved by the smallest boy in the largest candy store. I found some of the great specimens of my profession—Agassiz’s echinoderms, Raymond’s collection from the Burgess Shale. But I got a particular thrill from Patten’s eurypterids because I knew exactly why he had gathered them. Patten, like Dubois, had collected with a singular purpose. I had read his 1912 book—

The Evolution of the Vertebrates and Their Kin

—one of the curiosities of my profession. Patten’s book represents the last serious defense of the classic, though incorrect, theory for vertebrate origins—the attempt to link the two great phyla of complex animals by arguing that vertebrates arose from arthropods.

A head shield of

Eurypterus fischeri

collected by William Patten in Estonia.

Photograph by Rosamond W. Purcell

.

Patten identified eurypterids as the arthropod ancestors of vertebrates—hence his strong desire to collect them. But Patten was even more interested in a group that occurred with the eurypterids in some localities—jawless fishes of the genus

Cephalaspis

(meaning head shield). We now recognize these jawless fishes (class Agnatha) as the oldest vertebrates and precursors of all later forms, ourselves included. The Agnatha survive today as a small remnant of naked eel-shaped forms—the lampreys (genus

Petromyzon

) and the distantly related hagfishes (genus

Myxine

). But the original armored agnathans, popularly called ostracoderms (shell skinned), dominated vertebrate life for its first hundred million years and included a large array of diverse forms. Patten’s fascination with ostracoderms arose from his misinterpretation of their anatomy. Patten viewed

Cephalaspis

and its relatives as intermediary forms between arthropods and true fishes.

We usually tell the history of a profession as a pageant of changing ideas and their proponents. But we can also render a different and equally interesting account from the standpoint of objects studied. One could provide a fascinating history of astronomy from the moon’s point of view, and genetics receives a different, multifaceted account through the eyes of a fruit fly.

Cephalaspis

may be our best standard bearer for evolution.

The history of ideas about

Cephalaspis

—from its original misinterpretation as the head of a trilobite in the early 1800s to its present status as the archetypal ostracoderm for all aficionados of the group—provides more than a synopsis of evolutionary thinking. It also illustrates, in an unusually forceful way, the fundamental process of scientific discovery itself.

Popular misunderstanding of science and its history centers upon the vexatious notion of scientific progress—a concept embraced by all practitioners and boosters, but assailed, or at least mistrusted, by those suspicious of science and its power to improve our lives. The enemy of resolution, here as nearly always, is that old devil Dichotomy. We take a subtle and interesting issue, with a real resolution embracing aspects of all basic positions, and we divide ourselves into two holy armies, each with a brightly colored cardboard mythology as a flag of struggle.

The cardboard banner of scientific boosterism is an extreme form of realism, the notion that science progresses because it discovers more and more about an objective, material reality out there in the universe. The extreme version holds that science is an utterly objective enterprise (and therefore superior to other human activities); that scientists read reality directly by invoking the scientific method to free their minds of cultural superstition; and that the history of science is a march toward Truth, mediated by increasing knowledge of the external world.

The cardboard banner of the opposition is an equally extreme form of relativism, the idea that truth has no objective meaning and can only be assessed by the variable standards of different communities and cultures. The extreme version holds that scientific consensus is no different from any other arbitrary set of social conventions, say the rules for Chinese handball set by my old crowd on 63d Avenue. Science is ideology, and scientific “progress” is no improving map of external reality, but only a derivative expression of cultural change.

These positions are so sharply defined that they can only elicit howls of disbelief from the opposition. How can relativists deny that science discovers external truth? say the realists. Cro-Magnon people could draw a horse as beautifully as any artist now alive, but they could not resolve the structure of DNA or photograph the moons of Uranus. How, reply the relativists, can anyone deny the social character of science when Darwin needed Adam Smith more than Galápagos tortoises and when Linnaeus matched his taxonomy to prevailing views of divine order?

These extreme positions, of course, are embraced by very few thinkers. They are caricatures constructed by the opposition to enhance the rhetorical advantages of dichotomy. They are not really held by anyone, but partisans

think

that their opponents are this foolish, thus fanning the zealousness of their own advocacy. The possibility for consensus drowns in a sea of charges.

The central claim of each side is correct, and no inconsistency attends the marriage once we drop the peripheral extremities of each attitude. Science is, and must be, culturally embedded; what else could the product of human passion be? Science is also progressive because it discovers and masters more and more (yet ever so little

in toto

) of a complex external reality. Culture is not the enemy of objectivity but a matrix that can either aid or retard advancing knowledge. Science is not a linear march to truth but a tortuous road with blind alleys and a rubbernecking delay every mile or two. Our road map is not objective reality but the patterns of human thoughts and theories.

My position, as a variety of apple pie, is easy to state. It is also empty and tendentious as an abstract generality. This middle way, this golden mean, can only permeate our understanding by example.

Cephalaspis

provides one of the best demonstrations I know because this fish played a central role in three important and sequential views of nature’s order. Each view embodied its cultural context, but each also provided a framework for new and genuine objective knowledge about

Cephalaspis

. The new knowledge then helped to establish a revised view of natural order. Speaking of rhetoric in the best American tradition, culture and knowledge are rather like liberty and union—one and forever, now and inseparable.

Cephalaspis

, as its name implies, enclosed its head in a thick, bony shield. Much thinner scales covered everything behind, from front fins to tail. Since the scales usually disarticulate at death and are rarely preserved at all, most fossils of

Cephalaspis

include only the head shield. By itself, the shield is a peculiar and decidedly unfishlike object. It looks much like the head end of many trilobites (fossil arthropods), and was so classified until Louis Agassiz established the true affinity of

Cephalaspis

in his great monograph

Les poissons fossiles (Fossil Fishes)

, published in five large volumes between 1833 and 1843.

Agassiz confessed his wonder and puzzlement in his first paragraph on

Cephalaspis:

These are the most curious animals that I have ever observed; their features are so extraordinary that I had to make the most careful and scrupulous examination…in order to convince myself that these mysterious creatures are really fish.

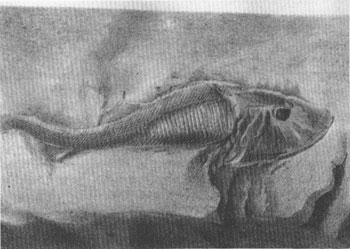

Agassiz reached the correct solution to his puzzle because his collection included some unusually well-preserved specimens, with the characteristic head shield indubitably attached to an undeniably fishy posterior (see figure). Yet while Agassiz began the modern history of

Cephalaspis

by placing this genus properly among the vertebrates, he could never resolve its relationship with other fishes for lack of crucial evidence. Agassiz particularly bewailed his failure to find any specimen exposing the lower surface of the head shield, where, he surmised (correctly), the mouth would be located. Thus Agassiz could never recognize the chief feature of jawlessness in

Cephalaspis

and could not identify the ostracoderms as structural precursors of all later vertebrates (jaws evolved from bones that supported gill arches behind the mouth of these jawless fishes).

Cephalaspis

, to Agassiz, remained an unplaceable oddball among fishes.

Although Agassiz could not fully resolve the status of

Cephalaspis

, he used this most peculiar of fishes as a linchpin for his theory of biological order.

Les poissons fossiles

is no simple list of old fishes; it is, perhaps most of all, a closely reasoned brief for Agassiz’s creationist world view—a theory that embodied the cultural consensus of 1830, but that Agassiz maintained doggedly to his death in 1873, long after its scientific demise in Darwin’s favor.

A figure from Agassiz’s

Les poissons fossiles

proving the vertebrate affinities of the head shield of

Cephalaspis. Photograph by Rosamond W. Purcell

.

Agassiz rooted his version of creationism in a complex analogy with his favorite subject, comparative embryology. Agassiz viewed embryonic growth as a tale of differentiation—more complex and specialized forms develop from simpler and more generalized precursors. These later specializations may proceed in several directions from a common initial form. Thus, a single (and simple) early embryo, representing a vertebrate prototype, might differentiate along several pathways into advanced fishes, reptiles, or mammals.

Agassiz then argued that the geological history of a group should match the embryological development of its latest and most advanced members. Early (geologically oldest) forms should be few, simple, and generalized; later relatives should be specialized and differentiated versions of these primordial archetypes. This scheme might sound evolutionary, but Agassiz explicitly rejected such a heresy. The geological sequence of separate creations paralleled embryological growth within each group because God’s orderly and benevolent plan permeated all developmental processes in nature.

Agassiz remained loyal to the classification of his mentor, the great French zoologist Georges Cuvier. He arranged all animals in four great groups: radiates (a hodgepodge by modern standards, but including such radially symmetrical forms as corals and echinoderms); mollusks; articulates (segmented worms and arthropods); and vertebrates. The four trunks are coequal and do not coalesce at life’s dawn, for they represent separately created plans for anatomy, not ancestors and descendants. But since geological history mimics embryological differentiation, prototypes of the four trunks from the oldest strata should be more similar than their modern representatives—for embryology is a tale of divergence from generalized roots.