Eleanor de Montfort: A Rebel Countess in Medieval England

Read Eleanor de Montfort: A Rebel Countess in Medieval England Online

Authors: Louise J. Wilkinson

Eleanor de Montfort

A Rebel Countess in Medieval England

Louise J. Wilkinson

Continuum International Publishing Group

| The Tower Building 11 York Road London SE1 7NX | 80 Maiden Lane Suite 704 New York NY 10038 |

© Louise J. Wilkinson, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publishers.

First published 2012

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4411-8219-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

6 Family, Faction and Politics

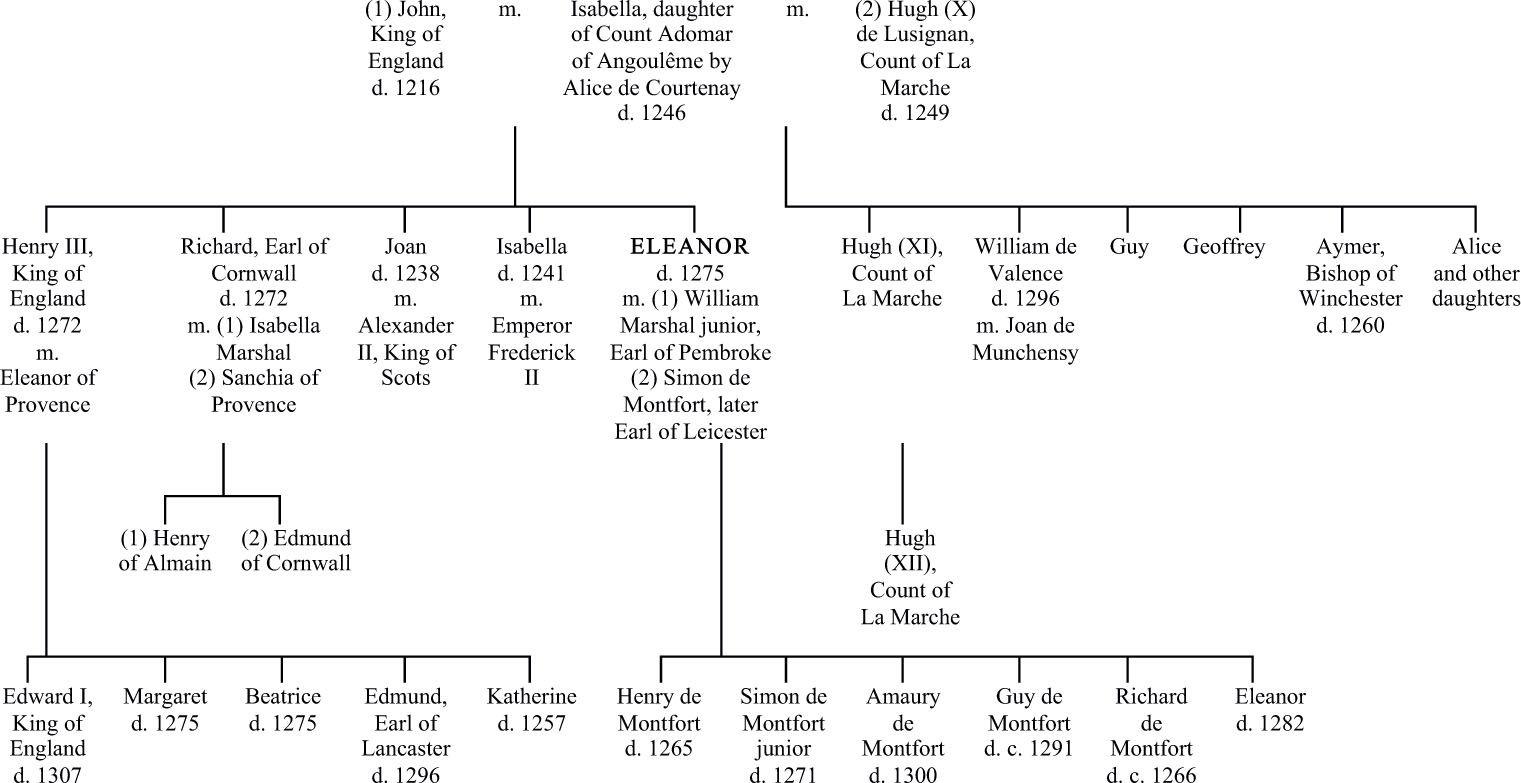

In his magisterial study

King Henry III and the Lord Edward

(1947), F. M. Powicke celebrated Eleanor de Montfort as ‘the most vigorous and passionate of the daughters of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, a greater force in affairs than her sisters the queen of Scots and the [Holy Roman] empress’.

1

Yet the life of this remarkable woman has long been overshadowed by the controversial career of her second husband, Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and his death and mutilation at the battle of Evesham in August 1265. Earl Simon was one of the leading figures in a baronial movement to reform the government of the realm that emerged during the latter part of King Henry III’s reign and reduced the king to a mere cipher at the hands of his opponents. As one of the key architects of what is now regarded by many historians as England’s first political revolution and the man who effectively held the king captive for fifteen months after Henry’s defeat at the battle of Lewes in May 1264, Earl Simon’s life has, quite understandably, attracted the interest of a whole host of modern scholars. The most recent biography, that by John Maddicott (1994), offers a fascinating insight into Earl Simon’s political career in England and France, the financial insecurities that he faced in supporting his growing family throughout the 1240s and 1250s, and the strength of his religious beliefs. Yet, there has been no new, detailed biography of Eleanor, his wife, since that which M. A. E. Green published in her six-volume work,

Lives of the Princesses of England from the Norman Conquest

in the mid-nineteenth century.

2

Admittedly, a surviving account roll from Eleanor’s household for 1265, the year of Evesham, has awakened the interest of a number of scholars. A printed edition of this roll in the original Latin was published by T. H. Turner in

Manners and Household Expenses of England in the Thirteenth and Fifteenth Centuries

(1841), and I am now preparing a separate English translation of Eleanor’s roll for publication by the Pipe Roll Society with a view to making this remarkable source accessible to as wide an audience as possible. William H. Blaauw devoted a chapter of his seminal work

The Barons’ War including the Battles of Lewes and Evesham

(first published 1844, second edition with additions by Charles H. Pearson 1871) to ‘Eleanor de Montfort and her sons’. Blaauw used the roll to discuss the provisioning of Eleanor’s household during this critical period in the Montfort family’s fortunes, the countess’s itinerary, the garrisoning of the castles at which she stayed, the visitors to whom she offered hospitality and the Montfortian allies with whom she corresponded. It was, however, Margaret Labarge, who, having examined Earl Simon and Countess Eleanor’s ‘personal quarrels’ with Henry III for a University of Oxford B.Litt thesis in 1939, made the most extensive study of the roll to date. Her analysis of Eleanor’s household roll formed the basis for a study of thirteenth-century baronial lifestyles, first published in 1965 as

A Baronial Household of the Thirteenth Century

and reprinted in 2003 as

Mistress, Maids and Men: Baronial Life in the Thirteenth Century

. Although Labarge readily acknowledged the impact of the civil war on the household, observing that ‘Even the sober items of … [Eleanor’s] account show how much political initiative … [this noblewoman] displayed’,

3

her work was primarily concerned with the practicalities of running a great household, focusing on the domestic concerns of the countess as its lady and the internal organization of her establishment. It therefore included chapters on ‘The Castle as a Home’, ‘The Lady of the House’, ‘The Daily Fare’, ‘The Spice Account’, ‘Wine and Beer’, ‘Cooking and Serving of Meals’, ‘Cloths and Clothes’, ‘Travel and Transport’ and ‘The Amusements of a Baronial Household’. By comparison, relatively little was said about Eleanor’s political career and her personal role in the Barons’ War of 1263–5. A valuable step towards remedying this omission was made in 2010, when, in a piece that readily acknowledged its debt to Labarge, the Japanese scholar Keizo Asaji devoted a chapter of

The Angevin Empire and the Community of the Realm in England

to a fresh appraisal of Eleanor’s account roll, with a view to examining ‘the importance of the baronial household against the background of thirteenth-century English political society’.

4

Somewhat intriguingly, Asaji compared Eleanor’s role in gathering and disseminating information for her husband and sons to that of a modern ‘relay station’.

5

More recently, in an article published in the

Journal of Medieval History

in 2011, Lars Kjær analysed the use made of food, drink and hospitality in the countess’s account, creating a persuasive case for treating them as ‘ritualised’ forms of ‘communication’ that were intended to bolster Eleanor’s and the Montfortians’ standing in the localities in which she resided in 1265.

6

This biography also makes use of Eleanor’s household roll in a way that is grounded, first and foremost, in examining Eleanor’s political activities and in considering the extensive networks of family and friends that she nurtured and maintained at this critical period in English history.

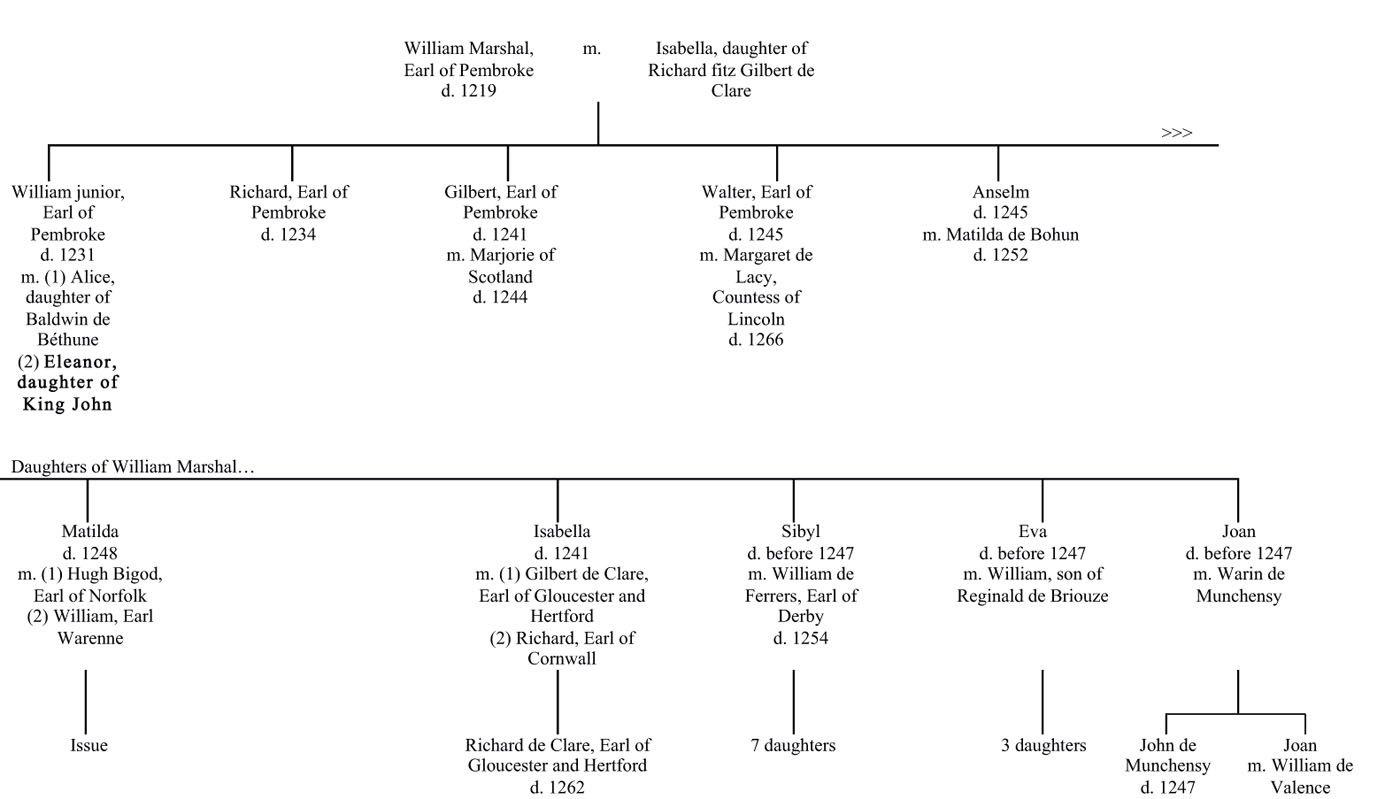

This present work is, then, the first detailed account of Countess Eleanor’s life for more than 150 years. It fills an important gap within the existing literature and serves as a timely companion volume to other biographical works on medieval women, such as Margaret Howell’s splendid study,

Eleanor of Provence: Queenship in Thirteenth-Century England

(1998). This book draws on the wealth of information from chronicles, letters, charters, public records, household accounts and the remains of the Montfort family archives to reconstruct the narrative of Eleanor’s life. In doing so, it provides an intimate portrait not only of Eleanor as a wife, mother and politician, but also of her changing relationships with her eldest brother, King Henry III, and with her nephew the Lord Edward, the future King Edward I, before, during and after the period of baronial reform and rebellion in England (1258–67). This biography also sheds significant new light on the countess’s experiences as a young bride during her marriage to her first husband, William Marshal junior, Earl of Pembroke, and as a widow after his untimely death in 1231. In particular, it challenges the motives traditionally ascribed by historians to her decision to take a vow of perpetual chastity during her first period of widowhood, arguing that Eleanor’s actions need to be considered against the political background of the settlement of England in the aftermath of the rebellion by her brother-in-law, Richard Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, in 1233–4.