Empire of Sin (14 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

By seven

A.M.

, nearly every police officer in the city of New Orleans was on the scene, along with scores of armed would-be vigilantes from the neighborhood. Police and several white civilians were ransacking the room of the man they now knew as Robert Charles, looking for evidence. Others were scouring the neighborhood for any sign of the man. The scene was chaotic—and volatile. When one witness claimed to have seen Charles ducking into a backyard privy, the reaction was swift. “

In a moment, a hundred or more infuriated men had run into the yard,” the

Item

reported. “Quicker than work could tell, they had torn up the floor of the vault and a veritable hail of lead … was being poured into the dark hole.” The outhouse was then pushed off its foundation and the pit below it was dragged, but the hole yielded only human waste and soiled paper.

Meanwhile, the discovery of

Charles’s cache of migration literature was fueling speculation that he was some kind of fanatical race agitator intent on “

evil toward the white man.” This revelation only stoked the anger of the crowd and hardened its determination to find him. Soon alleged sightings of the gunman were sending mobs of vigilantes out into an ever-widening area of the city. According to rumors, Superintendent of Police Gaster “wanted that man badly,” and had allegedly told searchers “not to hesitate in shooting the villain if he showed the slightest attempt to fight.”

By midday, the

largest manhunt in the history of New Orleans was turning the city upside down. Trains and ferries were stopped; citizen volunteers watched all major roads in the parish. Police were conducting floor-by-floor searches in public and private buildings throughout the city, as well as in Kenner, Gretna, and even as far away as Natchez and Vicksburg, Mississippi, where it was said some of Charles’s relatives lived. The hunt for the man the

Times-Democrat

was now calling “

one of the most formidable monsters that has ever been loose upon the community” went on for hours—and ultimately for days—but without success.

The ease with which Charles had eluded them caused considerable consternation among his would-be captors, and it wasn’t long before this frustration was being vented on a more available target—namely, the city’s black population. On Tuesday, the first day of the fruitless search, a few skirmishes broke out between groups of whites and blacks, mostly in the vicinity of the Fourth Street cottage. Police arrested many blacks who appeared to be sympathetic to the missing man—and

even one white visitor from New York who merely suggested that Charles may have shot the three policemen in self-defense. At the Sixth Precinct station house, threats to lynch Charles’s “accomplice” forced Superintendent Gaster to move Lenard Pierce to the relative safety of Orleans Parish Prison. But white crowds became increasingly belligerent over the course of the day, until rumors that Charles had been captured in suburban Kenner calmed some of their ire. Even so, by midnight there were numerous reports of black men and even women being beaten by the roving mobs.

By morning, when word spread that Charles had not been captured after all, the violence escalated again. Encouraged by inflammatory editorials in the morning newspapers—in particular a

Times-Democrat

piece that essentially blamed the black race “

as a class” for the crimes of its individual members—gangs of openly armed men raced through the streets of New Orleans, terrorizing any black person they could find. The atmosphere only worsened when the first edition of the afternoon

States

appeared. An editorial entitled

NEGRO MURDERERS

—written by the newspaper’s notoriously racist editor, Henry J. Hearsey—all but called upon the city’s white male population to retaliate in kind for what amounted to a secret and widespread black insurrection: “

We know not, it seems, what hellish dreams are arising underneath; we know not what schemes of hate, or arson, or murder and rape are being hatched in the dark depths,” Hearsey warned. “We are, and we should realize it, under the regime of the free Negro, in the midst of a dangerous element of servile uprising, not for any real cause, but from the native race hatred of the Negro.”

Not that many white New Orleanians—frustrated by increasing job competition with blacks—needed much encouragement. On Wednesday night, violence spread throughout the city. A mob of some two thousand whites formed in Lee Circle, at the foot of the towering monument to the Confederate general. In a scene hauntingly reminiscent of W. S. Parkerson’s rally against the Hennessy acquittals just nine years earlier, several orators spoke to the throng, inciting them to outrage, urging them to save the good name of New Orleans by punishing a black population that was clearly sheltering the murderous fiend in their midst. And so again an armed mob surged through the streets of New Orleans, with spectators cheering them on from the sidelines. Again “justice” was going to be served—only this time the victims were to be innocent blacks rather than innocent Italians.

The mob was, if anything, even more indiscriminate than the one of 1891. “

Unable to vent its vindictiveness and bloodthirsty vengeance upon Charles,” journalist Ida B. Wells later wrote, “the mob turned its attention to other colored men who happened to get in the path of its fury.” Streetcars were stopped and overturned; black passengers were taken out and beaten or shot. “

Negroes fled terror-stricken before the mob like sparrows before a picnic party,” the

Times-Democrat

reported. “The progress of the mob was like a torchlight procession all the way to Washington Avenue.… On every side cries of ‘Kill the Negroes,’ ‘shoot them down,’ and like expressions were freely used.”

By nine thirty, the mob—now numbering

some three thousand men and boys—had reached the new parish prison in the central business district, where Lenard Pierce was being held. But they found the doors barricaded and the building protected by a double cordon of armed policemen and sheriff’s deputies. The throngs tried to rush the doors, and there were several altercations between rioters and police—and even a few shots fired—but this time the line of blue held fast. “

The angry men swayed this way and that,” the

Times-Democrat

reported, “and their utter impatience in getting at the Negro Pierce … seemed to drive them into a state of madness.”

By ten

P.M.

, the frustrated crowd had moved on from the prison, breaking into smaller groups that roamed the city in search of prey. One group crossed Canal Street and entered the new Storyville District. “

The red-light district was all excitement,” a reporter for the

Picayune

later wrote. “Women—that is, the white women—were out on their stoops and peering over their galleries and through their windows and doors, shouting to the crowd to go on with their work, and kill Negroes for them.” Saloons, dance halls, and houses of ill fame—at least those catering to a black clientele—were by this time largely shut up tight, but the mob assailed them anyway. “Out went the lights in the honky-tonks,” the

Picayune

reported. “The music stopped in the dance houses, and the blacks, who were dancing, singing, and gambling, ran in the dark. Some hid under the houses … [others] sought refuge in outhouses and under cisterns.”

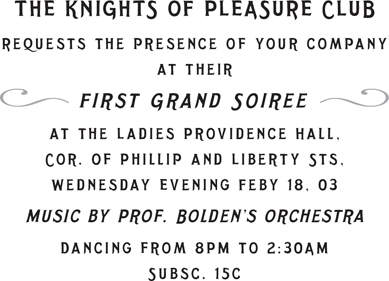

At the club called Big 25 on Franklin Street, Buddy Bolden was sitting in with Big Bill Peyton’s band, playing with Peyton on accordion, “Big Eye” Louis Nelson on clarinet and bass, Jib Gibbson on guitar, and a few others. According to Nelson, a woman ran in and warned them that a mob was heading into “the District,” as Storyville had also come to be known. Nelson was tempted to leave that minute, but Peyton calmed him down. “

Aah, we never had nothing like that in New Orleans yet,” Peyton said, “and it won’t happen tonight.” He told the band to just keep playing. But then they started to hear some shooting nearby, and everyone panicked. “Me, I was sitting at the inside end of the bandstand, playing bass,” Nelson later recalled. “All them boys flung themselves on me in getting away from the door and out toward the back. The bass was bust to kindling, and I sailed clear across the back of the room, so many of them hit me so hard all at once.”

The musicians and customers climbed out a back window into the alley behind the club—only to find that it was already filling with white rioters. So they ran in the other direction. “Me and Bolden and Gibbson was together,” Nelson continued. “We thought Josie Arlington might let us through her house in Basin Street. [But] when she saw who we was, she slammed the door, locked it, and start[ed] to scream. So we cut on through the lot next door, made it over the fence and on down Basin. Not one of us had a shirt on him by then, and Bolden had left his watch hanging on the wall near the bandstand. We might have been assassinated, but we was lucky enough to get to a friend’s house. We locked ourselves in and barred the doors.”

The rampage went on all night—in the District, the Vieux Carré, and any other neighborhoods where blacks might be found. It was clear that the rioters had one simple, ugly intent: “

The supreme sentiment was to kill Negroes,” as the

Picayune

put it. “Every darky they met was ill-treated and shot.” And through all of this, the New Orleans Police Department arrested no one.

By morning, three blacks had been brutally killed, with six more critically wounded. Around fifty others had received lesser injuries—including five whites, two of them shot by mistake and three others beaten or shot for merely objecting to the senseless violence. Fearing a second day of mayhem, then-mayor Paul Capdevielle, who had been out of town recovering from an illness, returned to the city. He ordered every saloon in the city closed, and called for the formation of a force of five hundred special volunteer police to quell the violence. By afternoon, he had three times that many, including hundreds of the city’s most prominent citizens. Business in New Orleans, after all, had come to a virtual halt by now, as huge numbers of workers—black

and

white—stayed away from their jobs; the riot was even having a negative effect on the city’s securities market. Something had to be done. “

The better element of the white citizens,” according to Ida Wells, “began to realize that New Orleans in the hands of a mob would not prove a promising investment for Eastern capital, so the better element began to stir itself, not for the purpose of punishing the brutality against the Negroes who had been beaten … but for the purpose of saving the city’s credit.”

Whatever their motivation, the citizens’ force did make progress in heading off the violence. By Thursday night, when the special police were supplemented by an influx of state militiamen, the city seemed more or less under control—but not before two more blacks had been killed and fifteen others non-fatally shot or beaten. And although a semblance of order now reigned, no one forgot the fact that Robert Charles was still at large, and there was no telling what might happen when that “

bloodthirsty champion of African supremacy” was finally caught.

I

N

a small room in the rear annex of 1208 Saratoga Street, just fourteen blocks from his home on Fourth, Robert Charles was waiting. He had been there—holed up in the single room that constituted the structure’s entire second story—for three days now, having come directly from the scene of the shootings early Tuesday morning. It was not, perhaps, the best place for him to find refuge. He was known in the neighborhood as a friend of the Jacksons, the family who rented most of the densely occupied duplex building from its white owner; any police investigator checking out the gunman’s friends and associates would hear about the Jacksons eventually. But Charles’s mobility was still limited by his leg wound. And as the owner of the most famous black face in the city of New Orleans, now emblazoned across the front page of every daily newspaper, he didn’t have many other options. Nor could he have had any illusions about how this adventure was likely to end. A black man who killed two white policemen in the New Orleans of 1900, no matter what the circumstances, would never be allowed to explain himself in court.

And so Robert Charles was preparing to defend himself. He still had his Winchester rifle, and in a first-floor closet under the building’s narrow staircase he had set up a small charcoal furnace. Here he was melting bits of lead pipe to make bullets. His intent was clear: if he was to die at the hand of a mob or the New Orleans police, he was going to take as many people with him as he could.

Charles’s vigil came to an end on Friday afternoon, when he saw a police patrol wagon pulling slowly into Saratoga Street. Superintendent Gaster had received a tip shortly before noon that day. A black informant had claimed that a family by the name of Jackson—thought to be relatives of the fugitive—was harboring him in their home. A few quiet inquiries had revealed the location of that home as 1208 Saratoga Street. And although this was only one of numerous leads Gaster had received in the days since the shootings, it was a plausible one. So he’d sent one of his best officers—Sgt. Gabriel Porteus, who had been

instrumental in turning away the mob at the parish prison on Wednesday—to check it out, accompanied by three other men from the Second Precinct.