Empire of Sin (18 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

THE YEARS IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING THE ROBERT Charles riot were not easy ones for black New Orleans. Bitterness over the four days of rampant violence did not pass quickly, and the twin insults of disenfranchisement and increasing segregation only grew more intolerable as the months passed. But despite the worsening situation—or perhaps partly because of it—the new music of the ghetto seemed to be thriving. By 1903, in fact, the “raggedy” sound was making inroads all over the city, often in some surprising venues:

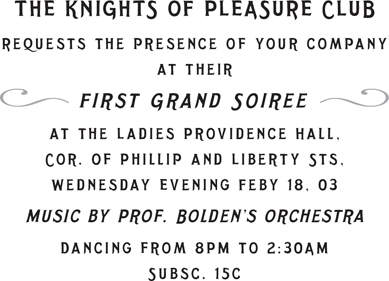

This advertisement—the only written notice of a Buddy Bolden performance surviving in the historical record—would seem to promise a somewhat staid and genteel event. After all, a “Grand Soiree” at something called the “Ladies Providence Hall,” with music by one “Professor” Bolden, sounds like an eminently respectable gathering. And perhaps it was; Bolden’s mother, Alice, was

a member of the Ladies’ Providence Society, and the city’s instrumental ensembles were by necessity flexible, playing music appropriate to whatever audience had hired them. But given that a Bolden performance the very next month was raided by police, this advertisement may be unrepresentative. A more typical Bolden venue was the Odd Fellows Hall on Perdido Street near Black Storyville, where a Labor Day ball that same year was promoted in a very different way: “

Tell all yo’ friends!” Bolden allegedly told a crowd some days before the event. “If you likes raggedy music, come one, come all! You all can dance any kind of way! And don’t forget, there’s a prize for the bitch who’ll shake it hardest—an’ I don’t mean her snoot!”

So life was hardly all doom and gloom in the black neighborhoods of New Orleans, and the new music both reflected and contributed to that fact. Audiences were clamoring for it, and musicians like Bolden were fast becoming celebrities. “

The main topic of talk with the people around [town] was music—like, who was a famous trumpet player,” one New Orleanian remembered. “They spoke of these great musicians … they were idolized.” Any event would become an excuse to hear jazz, and often the music itself was the excuse to hold an event. “

All over New Orleans on Saturday night there’d be fish fries,” according to bassist Pops Foster. “To advertise, you’d get a carriage with the horses all dressed up, a bunch of pretty girls, and then the musicians would get on, and you’d go all over, advertising for that night.… The fish fry that had the best band was the one that would have the best crowd.”

Out on the shores of nearby Lake Pontchartrain were three resorts—Spanish Fort, West End, and Milneburg—that were popular destinations for weekend outings. Each camp or pavilion would have its own band playing—all within earshot of the others, allowing for some fruitful cross-pollination of styles. “

The picnics at the lake were the ideal place for the younger people to hear the different bands and musicians,” guitarist Johnny St. Cyr explained. “We could hear them all at different camps and picnic grounds, and, needless to say, we all had our favorites.”

Storyville, too, soon became an important venue for the new music. At first, the establishments of the District were reluctant to hire bands—if customers were busy dancing, after all, they couldn’t be buying drinks (or women). But eventually the music proved too popular to ignore. Bolden’s band and other “hot” ensembles were soon

playing regularly at Storyville clubs like Nancy Hank’s Saloon and Big 25. Tom Anderson’s Annex

began by hiring a string trio (with piano, guitar, and violin) but eventually became a place for larger bands as well. Even the brothels wanted the new music—usually in the form of

a single piano “professor” playing in the parlor while clients chose their partners for the night. According to some reports, Countess Willie Piazza was the first madam to bring music into her house, hiring a legendary pianist known as John the Baptist to play on her famous white grand. Pianists such as Tony Jackson, Clarence Williams, and Jelly Roll Morton eventually found their own regular gigs in the District—at Lulu White’s, Gipsy Schaeffer’s, Hilma Burt’s, and the other Basin Street brothels. And while Storyville can in no way be considered

the

birthplace of jazz, as has sometimes been claimed, the various District venues did provide many early jazzmen with vital employment and helped to bring their music to a wider—and often non-black—audience.

Two of the most important settings for the development of early jazz opened in 1902.

Lincoln and Johnson Parks, located right across the street from each other just off South Carrollton Avenue, quickly became popular gathering places for the city’s black population. They were much closer to the central city than the lake resorts, and therefore were more accessible locales for

picnics, prizefights, and other entertainments throughout the week. Lincoln Park, the larger and more developed of the two, hosted a skating rink, a theater, and a performance “barn” where large dances and sporting events could be held. Lincoln was also the site of one of black New Orleans’ most storied events—

the weekly hot-air-balloon ascensions of Buddy Bartley, the park’s manager, who was also known to New Orleans police as a pimp and small-time criminal. The heavily advertised ascensions would feature the aerialist Bartley going up in the balloon (to a full orchestral accompaniment, of course) and flying around for a time before dramatically jumping from the basket and parachuting to the ground. How the balloon itself was brought to earth after its pilot had decamped is unclear—one hard-to-credit story holds that it was actually brought down with a rifle shot—but the spectacle was one of the most memorable entertainments of the era for many New Orleanians. Bartley’s regular ascensions, in fact, came to an end only after a mishap left him seriously injured. According to a witness: “

One Sunday, he drifted too far because of the high winds and when it was time for his parachute jump back to earth from the balloon, instead of landing in the park as usual, he wound up in the chimney of one of the houses fairly close to Lincoln Park—and what a mess he was.”

The attractions offered at Johnson Park across the street were usually less elaborate. The place was principally a baseball park, though it was also used for picnics and open-air concerts, and typically attracted a somewhat rougher crowd than its neighbor. It was in Johnson Park that Buddy Bolden normally played, often to the chagrin of those playing in the neighboring Lincoln Park. The regular band at Lincoln was the Excelsior, led by John Robichaux, a well-regarded Creole entrepreneur who had dominated the black music scene in the 1890s. On more than a few Sundays, Robichaux’s band would be packing them in at the Lincoln performance barn when Bolden and his crew were preparing to play at Johnson. But Bolden wouldn’t be worried, because he had a secret weapon—his cornet. According to his friend Louis Jones, “

That’s where Buddy used to say to [trombonist Willie] Cornish and them, say, ‘Cornish, come on, put your hands through the window. Put your trombone out there. I’m going to call my children home.…’ Buddy would start to play and all the people out of Lincoln Park would come on over where Buddy was.”

The crowds came not just because Bolden played loud—though he did do that—but because he played “hot” and “down-low.” Robichaux and his band of highly polished, academically trained musicians played “sweet”—that is, the straighter, more traditional and refined music beloved of the city’s educated Creoles of Color. But as one musician put it, “

Old King Bolden played the music the

Negro

public liked.” It was bluesier, more spontaneous, and at times downright raunchy. One crowd-pleaser that soon became Bolden’s signature number was “Funky Butt,” aka “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” a barrelhouse blues with ever-changing lyrics that could range from the light and comic to the low and coarse:

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say

,

Funky butt, funky butt, take it away …

You’re nasty, you’re dirty, take it away …

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden shout

,

Open up that window and let the bad air out

.

To Creoles like Robichaux and the other “dicty” people, as they were called, this kind of vulgarity was distasteful. As one musician put it, “

When the settled Creole folks first heard this jazz, they passed the opinion that it sounded like the rough Negro element.” But in the racially polarizing atmosphere of turn-of-the-century New Orleans, they often couldn’t avoid it. A lot of the skilled

trades traditionally pursued by Creoles were now being closed off to them in the new world of Jim Crow. Many were forced to turn to music as a profession rather than just a hobby, which meant playing the newer style of music pioneered by Bolden and the other early jazzmen.

Even an establishment figure like Robichaux soon found defectors in his own ranks.

George Baquet, a Creole clarinetist who played “sweet” with Robichaux for many years, found himself attracted to the new style and would sometimes sit in with Bolden on an occasional gig. One evening, the Bolden and Robichaux bands were playing in two rival saloons not far from each other. The two groups decided to have one of the cutting contests so beloved among black audiences of the day, the winner to be determined by the response of the audience. At first, Bolden’s band seemed to dominate, but then Baquet came to the rescue of the Robichaux group. He played a wild stunt routine in which he would gradually throw away various parts of his clarinet, while continuing to play it as if it were still whole. By the end, he was playing the mouthpiece alone—to the roaring approval of the crowd, who granted the win to Robichaux hands-down. What the Creole maestro himself thought of the performance is unknown—it was just the kind of low gimmick he likely would have disapproved of. But the rare win against Bolden must have been at least somewhat gratifying. As for Buddy himself, he was reportedly furious. “

George, why did you do it?” he hissed to Baquet afterward, apparently stung by being defeated at his own game.

Bolden’s music was particularly influential among younger downtown Creoles, who were less likely than their elders to cling to their sense of separateness from the Uptown African Americans. Jim Crow was forcibly pushing the two groups together, and it was the young who adapted most readily to the change—both socially and musically. “

Bolden cause all that,” one Creole musician admitted. “He caused these younger Creoles … to have a different style from the old heads.” But the young Creole musicians who began to play “hot” brought with them the greater reading skills and more polished technique of downtown, changing the new style even as it was changing them.

Bolden’s influence, in fact, was soon being felt well beyond the borders of New Orleans. The Bolden band and other groups often traveled out into the hinterlands, playing at harvest festivals, payday parties, parish fairs, and other events. And they spread the gospel of jazz wherever they went. “

I came to New Orleans in 1906, when I was fourteen years old,” pianist Clarence Williams explained. “It was after I heard Buddy Bolden, when he came through my hometown, Plaquemine, Louisiana, on an excursion, and his trumpet playin’ excited me so that I said, ‘I’m go in’ to New Orleans.’ I had never heard anything like that before in my life.”

A man who was to become one of the most important figures in the second generation of New Orleans jazzmen—

Edward “Kid” Ory—had a similar story to tell. Growing up in the sugar-mill town of LaPlace, some twenty-five miles upriver from New Orleans, young Ory would hear bands like Bolden’s, Edward Clem’s, and Charlie Galloway’s playing a banquet or other event and be intrigued. “Sometimes,” he later wrote,

“the guys would put the horns down and be drinking beer. I’d slip in and get one of the horns and try and blow it. I noticed how they were putting it into their mouth and I’d just [keep] on till I got a tone. We were all self taught.”

The son of a white father of Alsatian ancestry and a mixed-race mother, Ory had the

straight hair, light skin, and Anglo features to pass for white. But since he was black by law, he had to contend with the diminished job expectations allowed to members of that race. Becoming a musician seemed to be an excellent route out of the drudgery of a life of sugar production. So Ory soon formed a band with a few like-minded friends. At first, since none of them could afford instruments, they styled themselves as a “humming” group, harmonizing tunes on a nearby bridge at night. “

It was dark and no one could see us,” Ory recalled, “but people could hear us singing and they’d bring us a few ginger cakes and some water. We hummed and when we knowed the tune itself, the melody, the others would put a three- or four-part harmony to it. It was good ear training.”

Eventually, Ory’s group

made their own musical instruments, constructing a five-string dinner-pail banjo, a cigar-box guitar, and a soapbox bass. “

After finishing the three instruments, we started practicing in the daytime, but evenings would find us drifting to our favorite spot … the bridge … and the people, especially the youngsters, found us there and would hang around listening to us play, and they would start dancing there in the dusty road. It made us feel wonderful.…”