Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 (34 page)

Read Empires of the Sea - the Final Battle for the Mediterranean 1521-1580 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #Military History, #Retail, #European History, #Eurasian History, #Maritime History

WITH THE SHIPS SPREADING OUT,

Don Juan stepped down from the elaborately carved poop of the

Real.

He was wearing brilliant armor that glittered in the autumn sun, and carried a crucifix in his hand as he transferred into a light racing frigate and ran along the line of ships, putting heart into the men. As he passed under the stern of Sebastian Venier’s ship, the old hothead saluted him. With their minds fixed on ultimate things, all grievances were forgotten.

To each national contingent Don Juan offered words of encouragement. He urged the Venetians to avenge the death of Bragadin. To the Spanish he called for religious duty: “My children, we are here to conquer or to die as heaven may determine. Do not let our impious foe ask of us ‘Where is your God?’ Fight in his holy name, and in death or victory you will win immortality.” He visited two of the lumbering galleasses passing through the fleet line and urged them to hurry to their station. He promised liberation for all the Christian galley slaves if they fought well, and ordered their shackles to be removed. It was in fact a promise that he could not guarantee, as only the oarsmen on his own ships were within his gift. The Muslims were now handcuffed as well as chained, for fear of uprisings during the fight. For them there would be no escape if the ship went down.

Everywhere there were final preparations. Armorers moved among the Christian rowers, striking off shackles and handing out swords; weapons, wine, and bread were stockpiled in the gangways; priests offered words of comfort; the arquebusiers checked their powder and their slow-burning fuses; Spanish veterans of the Morisco wars sharpened their pikes and donned their steel casques. Commanders strapped on breastplates and helmets, flipping their visors up to catch the sea wind and the stink of the ships. Surgeons spread out their instruments and fingered the bite of their saws. Thousands of nameless galley slaves strained at the oars to the crack of the overseers’ whips and the steady pounding of drums. With their backs to the enemy, they rowed forward at a steady pace.

A few individual names stand out among the anonymous thousands on the Christian ships: Aurelio Scetti, Florentine musician, had been twelve years in the galleys for murdering his wife. On the

Marquesa,

the Spaniard Miguel de Cervantes, twenty-four years old, bookish and desperately poor, was a volunteer; on the morning of the battle he was ill from fever but tottered from his bed to command a detachment of soldiers at the boat station. Another sick man, sergeant Martin Muñoz, aboard the

San Giovanni

from Sicily, also lay below with fever. Sir Thomas Stukeley, English pirate and mercenary, possibly the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, commanded three Spanish ships. Romegas, detached from the Malta galleys, was with Colonna on his flagship, an appointment that would save his life. Antonio and Ambrogio Bragadin, kinsmen of the martyr of Famagusta, commanding two galleasses, waited in the front line, itching for revenge. And on Don Juan’s flagship was one particularly fresh-faced Spanish arquebusier. Her name was Maria la Bailadora (the flamenco dancer); she had disguised herself to accompany her soldier lover to the wars.

Five miles distant, the Muslims were making their own preparations. Ali’s fleet was also a mixture of elements: imperial squadrons from Istanbul and Gallipoli, the Algerians and more informal corsair bands in small galliots. All the great commanders were present: the beys of the maritime provinces of Rhodes, Syria, Naplion, and Tripoli; the sons of Barbarossa, Hasan and Mehmet; the commander of the Istanbul arsenal, Kara Hodja the Italian corsair; and Uluch Ali out on the left wing. There was evidently some small chafing between the different factions, between the “deep” Muslims and the opportunist renegades “with pork flesh still stuck between their teeth,” as well as between the skillful corsair captains and the sultan’s imperial placeholders. Ali Pasha’s plan was to run his galleys on the right wing under Shuluch Mehmet hard against the Greek shore; with their shallow draft and the commander’s knowledge of the coastal waters, Ali was confident they could outsmart and outflank the opposing Venetians. He ordered cavalry to stand to on the shore if the Venetians tried to beach their ships and run. Uluch Ali was desperately worried by this tactic. The plan turned on a calculated gamble. If it failed, the reverse might happen: the Muslims could be tempted to escape by land. Uluch Ali would have preferred an open-sea engagement, where an outflanking movement would be more clear-cut.

The Muslim fleet carried fewer cannon and arquebusiers than the enemy but many archers, whose vastly superior speed of fire could impale a Spanish hand gunner thirty times over while he was still reloading. They fought without armor, and their ships were not reinforced with wooden parapets that could protect the men against sustained gunfire. The aim was to be quick and agile.

To the calling of the imams, the men performed ritual ablutions and prostrated themselves in prayer. They tensioned their bows and dipped their arrows in poison; the decking was smeared with oil and butter, making it slippery for the heavily shod Europeans to keep their footing in a boarding raid, while the Muslims generally fought barefoot. The Christian galley slaves were forbidden on pain of death to look over their shoulder at the approaching foe, for fear of breaking stroke; when the ships tangled, the slaves were to hide under the benches. But Ali was a generous commander with a strong sense of honor. While Don Juan was double-shackling his Muslim oarsmen, the pasha made his Christian slaves a promise. Speaking to them in Spanish, he said: “Friends, I expect you today to do your duty by me, in return for what I have done for you. If I win the battle, I promise you your liberty; if the day is yours, God has given it to you.” It was a promise certainly within his power to fulfill. Ali had his two sons of seventeen and thirteen on board with him. As they were being transferred to another ship, he called them to him and reminded them of their duty. “Blessed be the bread and the salt you have given us,” they gravely replied. It was a touching moment of filial piety. Then they were gone.

Ali could now make out the Venetian galleasses becalmed on the water in front of the Christian fleet. They puzzled and worried him. In the Ottoman ranks, there was some general apprehension of heavily gunned round ships. The Turks had been warned of these vessels by captives, but the word was that the ships were armed with only three artillery pieces at bow and stern. It was impossible to understand what the Venetians were up to.

Four miles off, the red-hulled

Sultana

fired a blank shot; it was a personal address to the

Real,

an invitation to fight. Don Juan replied with purpose: his shot contained a live round. Ali ordered his helmsman, Mehmet, to make for the

Real.

The great green banner of Islam, precious above all the emblems of Islamic war, with the names of God intertwined twenty-nine thousand times, was hoisted aloft—the green and the gold thread glittered in the sun that was now catching the Muslims in the eye.

IN THE CHRISTIAN FLEET,

Don Juan arranged a matching piece of religious theatre. At a signal, crucifixes were raised aloft on every ship; the pope’s mighty sky-blue banner decorated with the image of the crucified Christ was hoisted on the

Real.

Don Juan knelt at the prow in his dazzling armor, imploring the Christian God for victory. Thousands of armed men fell to their knees. Friars in brown or black robes held up crosses to the sun and sprinkled holy water on the men and murmured absolution. Then they stood up and roared the names of their protectors and saints in Spanish and Italian. “San Marco! San Stefano! San Giovanni! Santiago y cierra España! Victoria! Victoria!” Trumpets rang brightly; the low-frequency thudding of the timekeepers’ drums beat an insistent tattoo; on the Muslim ships, the blare of zornas and cymbals, the men calling out the names of God, chanting verses from the Koran, and shouting to the Christians to advance and be massacred “like drowned hens.” And in a fit of exuberance beyond rational thought, Don Juan, whose dancing had been so noted at Genoa, “inspired with youthful ardor, danced a galliard in the gun-platform to the music of fifes.”

THERE WAS STILL TIME,

in the words of Girolamo Diedo, a Venetian official at Corfu, for both sides to take in the frightening beauty of the spectacle. “Hurtling towards each other, the two fleets were a quite terrifying sight; our men in shining helmets and breastplates, metal shields like mirrors and their other weapons glittering in the rays of the sun, the polished blades of the drawn swords dazzling men full in the face even from a distance…. And the enemy were no less threatening, they struck just as much fear in the hearts of our side, as well as amazement and wonder at the golden lanterns and shimmering banners remarkable for the sheer variety of their thousands of extraordinary colours.”

A third of a mile in front of the Christian fleet, four of the galleasses were now in position, spaced out at intervals; two on the right wing lagged and were only just up with the front line. The Venetian gunners crouched with lighted tapers, eyeing the two hundred eighty Muslim galleys closing fast. Arquebusiers fingered their rosaries and murmured prayers. Heartbeats raced. They braced themselves against the wall of noise. At one hundred fifty yards, an order: matches were set to the touchholes. It was just before noon.

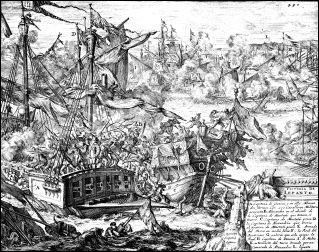

THERE WAS A SERIES OF BRIGHT FLASHES,

a thunderous roar, then the smoke that would obscure everything. At this distance it was impossible to miss. Iron balls ripped into the advancing ships. Galleys just burst asunder under the impact. “It was so terrible that three galleys were sunk just like that,” recorded Diedo. Confusion checked the Ottoman advance; ships crashed into one another or tried to halt. The

Sultana

had a stern lantern shot away. The oared galleasses turned through ninety degrees to deliver a second round. Ali ordered up the stroke rate to shoot past the mouth of the guns as fast as possible. The line tacked and opened to avoid the floating gun towers. Broadside on, the Ottoman line was now raked by arquebus fire. When a helmsman was shot down, the vessel staggered and veered; then a row of turbaned soldiers caught in profile would be felled by a volley of bullets. The galleasses made another quarter turn. “God allow us to get out of here in one piece,” shouted Ali, watching the wreckage being inflicted on his battle line, now jagged, holed, and in disarray. Sweeping beyond the guns, the Ottoman galleys opened fire at the main Christian line, but they aimed too high. Don Juan waited for the Ottomans to close; with their rams cut away, the cannon could fire close and low. As Ali’s ships pressed forward, the Christian guns erupted, each commander choosing his moment. Black smoke blew favorably on the west wind, obscuring the Muslim aim. Even before the collision of the two lines, a third of Ali’s ships had been crippled or sunk, “and already the sea was wholly covered with men, yardarms, oars, casks, barrels, and various kinds of armaments—an incredible thing that only six galleasses should have caused such destruction.”

CHAPTER

21

Sea of Fire

Noon to nightfall, October 7, 1571

B

Y THIS TIME FURIOUS FIGHTING

had already broken out close to the shore. The Ottoman right wing, under Shuluch Mehmet, had sheered away to avoid the withering fire of the galleasses. Now they looked to outflank the Venetian-led left under the command of Agostino Barbarigo. Shuluch aimed to exploit the narrow corridor of the coastal shallows, into which he knew the weightier Venetians dared not venture. “Shuluch and Kara Ali, outpacing all the other Ottoman galleys, drove furiously towards our line,” wrote Diedo. “As they neared the shore, they slid between the shallows with the foremost ships of their squadron. These waterways were familiar to them; they knew exactly the depth of the sea above the shoals. Followed by four or five galleys, they planned to take our left wing in the rear.”

Before the Venetians knew what was happening, these galleys had slipped around the end of Barbarigo’s line and were assaulting the exposed vessels on the outer tip from both sides. If many more outflanked Barbarigo’s wing, the situation would be critical; the Christians would be suddenly taken from behind. Barbarigo interposed his own ship to block the way and was instantly engulfed in a firestorm. So many arrows whipped through the air that his stern lantern was bristling with shafts; the lead galleys were furiously assaulted, their decks swept by arquebus fire, their commanders and senior officers shot down one by one as the Ottomans attempted to crush the outer flank. For an hour Barbarigo’s ship struggled valiantly, its deck fiercely contested by boarding parties. Behind his visor, the commander’s muffled instructions were being lost in the din of battle. Incautiously he flipped the visor up, shouting that it was better to risk being hit than not to be heard. Minutes later an arrow struck him in the eye; he was carried below to die. The battle for the flagship intensified; Barbarigo’s nephew Giovanni Contarini brought his own galley up to help and was, in turn, shot dead.

Shuluch looked close to success, but the Venetians had come for revenge; many of their ships were from Crete, the Dalmatian coast, and the islands, all ravaged by Ali Pasha’s summer raids. They fought desperately and without regard. Slowly the tide started to turn. Galleys from the reserve swung up to help; troops were fed onto the stricken ships from the rear. Panic erupted on an Ottoman galley when the Christian slaves broke free and launched a furious assault on their masters, raining smashing blows with their whirling chains. One of the galleasses crept toward the shore and began to pulverize the Ottoman ships. Shuluch’s flagship was rammed and had its rudder sheared off; then it was holed and started to sink; it just sat waterlogged in the shallows. Shuluch, identified by his brilliant robes, was fished out of the sea more dead than alive. So severe were his wounds that the Venetians decapitated him on the spot as an act of mercy. Following Shuluch’s ship, the whole squadron had drifted toward the shore and was now pinned there. “In this vast confusion,” wrote Diedo, “many of our galleys, especially those nearest the centre of the fleet…made a general turning movement toward the left in good order and came to envelop the Turkish ships, which were still putting up a desperate resistance to ours. By this adroit manoeuvre they held them enclosed, as in a harbour.” The Ottoman right wing was trapped.

It was now that Uluch’s worst fear was realized. Seeing the temptation of the shore, the Muslims gave up the fight. There was a confused flight for the beach. Ships crashed into one another; men hurled themselves overboard, scrabbling and drowning in the depths and the shallows. Those behind used the trampled bodies of their compatriots as a bridge to land. The Venetians were in no mood for prisoners. They put out longboats and pursued them ashore with shouts of “Famagusta! Famagusta!” One enraged man, finding no other weapon, grabbed a stick and used it to pin a fallen opponent to the beach through the mouth. “It was an appalling massacre,” wrote Diedo. In the confusion, a band of Christian galley slaves on the Venetian ships who had been unshackled on Don Juan’s orders took stock of their options and decided that instant freedom was better than a general’s promise. Leaping ashore with the weapons they had been given, they ran off to take their chances as bandits in the Greek hills.

SHORTLY AFTER MIDDAY

the heavyweight centers of the two fleets also collided. The fancifully named galleys of the Venetians and the Spanish—the

Merman,

the

Fortune on a Dolphin,

the

Pyramid,

the

Wheel and Serpent,

the

Tree Trunk,

the

Judith,

and innumerable saints—shattered into the squadrons from Istanbul, Rhodes, the Black Sea, Gallipoli, and Negroponte, commanded by their captains: Bektashi Mustapha, Deli Chelebi, Haji Aga, Kos Ali, Piyale Osman, Kara Reis, and dozens more. One hundred fifty fully armed galleys plowed into one another.

THE CHRISTIANS HAD ROWED

slowly toward this collision, intent on holding their line. The Ottomans were ragged and disarranged by the blizzard of shot from the galleasses but moved forward with eager velocity, skimming the calm sea, their lateen sails raked back, their guns blazing. The principal players on each side clustered at the nerve center of the battle: On the Ottoman side, Ali Pasha in the

Sultana,

with Pertev Pasha, the army commander, on his right shoulder; Mehmet Bey, governor of Negroponte with Ali’s two sons on his left; Hasan Pasha, Barbarossa’s son; and a group of other experienced commanders. Don Juan steadied himself on the poop of the

Real

with Marc’Antonio Colonna and Romegas in the papal flagship on one side, Venier on the other. Philip would have been appalled by Don Juan’s sense of risk. He was horribly visible standing before the banner of crucified Christ in his bright armor, sword in hand, refusing pleas to retreat into his cabin. Ali stood on his poop in equally brilliant robes, armed with a bow. Both men were playing for high stakes, oblivious of the wise words Don Garcia once addressed to La Valette: “In war the death of the leader often leads to disaster and defeat.”

As the ships closed, the

Sultana

loosed off shots from its forward guns. One ball smashed through Don Juan’s forward platform and mowed down the first oarsmen. Two more whistled wide. The

Real,

with its forward spur cut off, could shoot lower, and waited until the enemy was at point-blank range, “and all our shots caused great damage to the enemy,” wrote Onorato Caetani, captain-general of the pope’s troops, aboard the

Griffin.

The

Sultana

seemed to be making for the Venetian flagship, then dipped its helm at the last moment and slammed into the

Real,

bow to bow; its beaked prow rode up over the front rowing benches like the snout of a rearing sea monster, crushing men in its path. The vessels recoiled in shock, but remained interlocked in the entangled mess of rigging and spars.

Sea of fire

There were similar shattering collisions all along the line. The papal flagship, directed by Colonna in support of the

Real,

was hit by Pertev Pasha’s ship, spun around, and slammed into the side of the

Sultana,

just as another Ottoman galley careered into Colonna’s stern. On the other side, Venier also moved up but found himself immediately engulfed in a separate mêlée. The Christian line had already been breached, and the sea was a tangled mass of thrashing ships.

WHAT THE SURVIVORS WOULD REMEMBER

—as far as they remembered anything from the flash-lit moments of battle—was the noise. “So great was the roaring of the cannon at the start,” wrote Caetani, “that it’s not possible to imagine or describe.” Behind the volcanic detonation of the guns came other sounds: the sharp snapping of oars like successive pistol shots, the crash and splinter of colliding ships, the rattle of arquebuses, the sinister whip of arrows, cries of pain, wild shouting, the splash of bodies falling backward into the sea. The smoke obscured everything; ships lit by sudden shafts of sunshine would lurch through the murk as if from nowhere and tear at one another’s sides. Everywhere confusion and noise: “a mortal storm of arquebus shots and arrows, and it seemed that the sea was aflame from the flashes and continuous fires lit by fire trumpets, fire pots and other weapons. Three galleys would be pitted against four, four against six, and six against one, enemy or Christian alike, everyone fighting in the cruellest manner to take each other’s lives. And already many Turks and Christians had boarded their opponents’ galleys fighting at close quarters with short weapons, few being left alive. And death came endlessly from the two-handed swords, scimitars, iron maces, daggers, axes, swords, arrows, arquebuses, and fire weapons. And beside those killed in various ways, others escaping from the weapons would drown by throwing themselves into the sea, thick and red with blood.”

AFTER THE FIRST SPLINTERING COLLISION

between the two flagships, men on both sides attempted to board. There were four hundred Sardinian arquebusiers on the

Real,

eight hundred fighting men in all, jam-packed shoulder to shoulder so that each had no more than two feet of space. Ali had two hundred arquebusiers and one hundred bowmen. At the first moment, “a great number of them, very bravely, leaped aboard the

Real;

at the same moment many men from the

Real

leaped aboard their ship.” According to legend, Maria the dancer was one of the first across, sword in hand. The battle became cut and thrust at close range, the chained rowers trying to duck under the narrow benches, while armed men clattered down the central deck. The Muslims were quickly forced back from the

Real;

the Spanish troops made it as far as the

Sultana

’s mainmast before they were stopped; its intricate walnut decking was soon slippery with oil and blood as both sides hacked and slipped in the muck. Each ship was supported from behind by other galleys that fed a transfusion of fresh men up rear ladders as those at the bows collapsed and died. At close range, missiles were deadly. A man armored in a breastplate and back plate could be skewered right through by a single arrow or felled by a bullet. Don Bernardino de Cardenas on the

Real

was hit on the breastplate by a shot from a swivel gun; it failed to rupture his armor but he died later from the force of the blow. Islam’s green banner was peppered with shot, but the Christians were forced back.

Both sides understood that the flagships were key to the battle. Makeshift barricades were erected at the mast stations to thwart boarders, so that the fight for the boats resembled street fighting in a narrow alley. So close were the men that they were massacred in droves; more were fed in from behind. Flights of arrows from the

Sultana

whipped across the sky, hitting the deck of the

Real

so fast they seemed to be growing out of it; according to one eyewitness, the Christian ships bristled like porcupines. The fortunes on the flagships reversed and the Ottomans stormed back up the

Real.

In the midst of this mayhem, Don Juan’s pet marmoset was seen pulling out arrows from the mast, breaking them with its teeth, and throwing them into the sea.

On either side of the

Real

and all down the line, the fighting was furious. Venier, trying to come up to the aid of the flagship, hit the

Sultana

amidships but was surrounded on both sides. Only the appearance of two Venetian galleys from the reserve saved his life. Both their captains were killed. Bazán’s reserve galleys, kept back to buttress the line at critical moments, were now being pumped in to stem the tide of battle. Colonna repulsed the galley of Mehmet Bey with Ali’s sons aboard. Farther up the line the galleys of the corsairs Kara Hodja and Kara Deli attempted to storm the

Griffin,

Kara Hodja running at the front of his men, but the arquebus fire was starting to tell. “Giambattista Contusio felled Kara Hodja with an arquebus and one after another until there weren’t six Turks left alive.” And the Spanish pikemen, who had learned to fight in organized drills in the Alpujarras, were deadly at close range. Once aboard an enemy ship, they swept down the deck, impaling resisters and butting them into the sea. Aurelio Scetti recorded the desperate courage of his fellow Christian galley slaves liberated from their chains to fight: “There was a high number of deaths among the Turks when the Christian prisoners jumped aboard the enemy ships, telling themselves, ‘Today we either die or we earn our freedom.’”