Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (36 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

Indian culture is unique in the world for its rigorous analysis of its own language, which it furthermore made the central discipline of its own culture. The Sanskrit word for grammar,

vyākara a

a

, instead of being based, like the Greek

grammatikē

, on some word for

word

or

writing

, just means

analysis:

so language is the subject for analysis par excellence.

Patanjali, a noted grammarian of the second century BC, wrote at the beginning of his work the

Mahābhā⋅ya

(’great commentary’) that there were five reasons for studying grammar: to preserve the Vedas, to be able to modify formulae from the Vedas to fit a new situation, to fulfil a religious commitment, to learn the language as easily as possible, and to resolve doubts in textual interpretation.

3

So it is clear that even at this stage, a good millennium after the composition of the Vedas, when the language had already changed quite considerably, enhancing the use of language for religious purposes was still felt to be the central point of grammar.

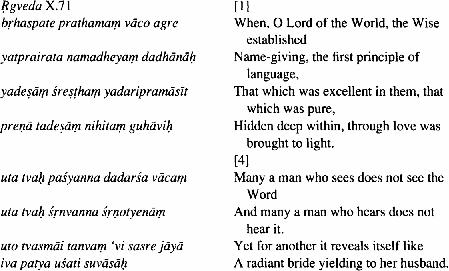

And religious uses have always loomed large in the figure that Sanskrit cuts in the world. Hindu liturgies have been intoned in the language over a continuous period of 3500 years, which is probably the age of the oldest hymns in the Rig Veda. The gods chosen to be the focus of worship have changed over the millennia, from Agni (’Fire’), Savitri (’Sun’), Varuna and Rudra in the Vedas, to Śiva, Krishna, Ganesha and Kali (and many others) today, but some gods are still with us (notably Vishnu), and the language has changed very little. In fact, in the Rig Veda there is one hymn that is an invocation of Vāc, speech itself. Here are two of its verses:

The last words show a blending of sexual and mystical imagery, often found in Sanskrit; but they also show that the skills of the linguist were early recognised. This is particularly interesting in that the discipline of grammar as it had been developed was an analysis not primarily of the religious language of the Vedas, but of a different, slightly simpler, and therefore presumably later, dialect.

Pā ini

ini

, the original fifth-century BC doyen of Sanskrit grammar, has to give extra rules to generate the forms used in the Vedas (called

chandas

) from a base in ordinary Sanskrit (designated as

bhā ā

ā

—’speech’). (Panini probably lived in the academic community of

Tak aśilā

aśilā

, known to the Greeks as Taxila, near modern Rawalpindi in the extreme north-east of the subcontinent, now part of Pakistan.)

Furthermore, the grammar that the tradition had defined was a vast system of abstract rules, made up of a set of pithy maxims (called

sūtras

, literally ‘threads’) written in an artificial jargon. These sutras are like nothing so much as the rules in a computational grammar of a modern language, such as might be used in a machine translation system: without any mystical or ritual element, they apply according to abstract formal principles.

*

Formulation in sutras became the key feature of Sanskrit academic texts, but using maxims in regular Sanskrit and not this complex meta-language. Whereas Western didactic texts until the modern era were formulated in some Greek tradition as a set of axioms and theorems (after Euclid), or more often as didactic verse (after Hesiod), the preferred approach in the Sanskrit tradition has been to encapsulate treatises as a series of memorable aphorisms, usually phrased as verse couplets. So much so that there is even a sutra to define the qualities of a good sutra:

svalpāk

aram asandigdha

sāravad viśvatomukham

astobham anavadya

ca sūtra

sūtravido vidu

brief, unambiguous, pithy, universal,

non-superfluous and faultless the sutra known to the sutra-sages.

This approach was very much a part of another distinctive feature of Sanskrit linguistic culture, namely a strong ambivalence about the value of writing. Reliance on language in its written form was seen as crippling, and not giving true control over linguistic content. Hence this proverb:

pustakasthā tu yā vidyā parahastagatam dhanam

Knowledge in a book—money in another’s hand.

4