Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (48 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

There is also an interesting curiosity in one of the other writing systems used in this vast area of Asia.

*

Japan owes the order of symbols in its syllabary, the so-called

kana

, or

go-jū-on

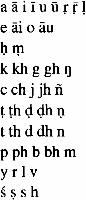

, ‘fifty sounds’, to the order of letters in Indian alphabets. The order of Sanskrit letters is conventionally

This is not an arbitrary order like our ABCD…

†

Rather it appeals to various purely phonetic properties of the sounds represented. So, for example, all the consonants are placed in an order where tongue contact gradually advances from the back to the front of the mouth cavity. And the nasal consonants (

m, n

, etc.) always come immediately after the other consonants formed at the same place of articulation. The strange order of the vowels is partly conditioned by the fact that most instances of

e

and

o

in Sanskrit actually derive from the diphthongs

ai

and

au

, and so are well classified next to their long equivalents

āi

and

āu.

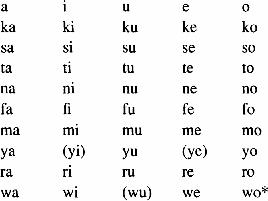

Now the Japanese

kana

represent syllables, rather than individual consonants. Their pronunciation has definitely changed over the last millennium, but using the most ancient pronunciation reconstructible, we can state the conventional order as:

Immediately we note that the arbitrary order of the vowels (a i u e o) is precisely as in Sanskrit, although this has no motivation in Japanese grammar. Furthermore, although there are many fewer consonants in Japanese than in Sanskrit, they occur in almost exactly the same order as in the Sanskrit alphabet. In fact, there is only one apparent exception, s, which occurs where c or should be, not at the end like the Sanskrit sibilants. In fact there is reason to believe that the pronunciation of this phoneme was actually [š] (English ‘sh’) or [t

should be, not at the end like the Sanskrit sibilants. In fact there is reason to believe that the pronunciation of this phoneme was actually [š] (English ‘sh’) or [t

s

], when the conventional order was set up, which means it would be closest to Sanskrit

c

(English ‘ch’, [tš]).

This thoroughgoing intellectual borrowing at the root of the writing system demonstrates that not just the sound of the Buddhist chants but also elements of the traditional analysis of the language had spread to Japan with Sanskrit.

Another example of Sanskrit intellectual influence on the technology of writing is the Tibetan script, which we first see in use in the eighth century AD, derived directly from the Siddha script. The earliest-known use of it is on a stone pillar at Žol near Lhasa, dated to 764.

42

It is not quite clear if Tibet owes its literacy to Buddhism, or to attempts to modernise administration. The era of the first surviving inscriptions is precisely the time when Buddhism first came to Tibet, with the monk

Śāntarak ita.

ita.

But there is no mention of Buddhism on the Žol pillar inscription, which is a record of a royal minister’s achievements.

43

Whatever the motivation, it is clear that the Tibetan alphabet was inspired by an Indian model, and one that was used for the writing of Sanskrit or

Prakrit. And Tibetan writing, once established, was very largely taken up with the translation of Buddhist classics from Sanskrit or Pali. This became such an industry that there was a Tibetan royal commission in the early ninth century to establish precise rules for equivalences (comparable to the ‘controlled language’ used in some industrial translation today). The result was a lowering of the literary skill displayed in translation, but such punctilious work was done that it is often possible to reconstruct lost Sanskrit originals simply on the basis of their Tibetan versions.

These religious foundations of Tibet’s Sanskrit culture were surmounted by a superstructure of wider-ranging classical literature in the thirteenth century, for then Muslim invaders devastated all the centres of higher learning in northern India, and many scholars fled northward into Tibet with their books. Nine Sanskrit pundits accompanied the

Khatšhe pantšhen Śākyašrībhadra

to Tibet in 1206, and fifty years later there was collaboration on Sanskrit drama, poetry and poetics between the Indian pundit

Lak mīkara

mīkara

and the Tibetan scholar

šo -ston Rdo-rdže rgyal msthan

-ston Rdo-rdže rgyal msthan

.

44

It is somehow reassuring to think that eight hundred years ago Tibet was a refuge for Buddhists fleeing from marauding infidels in northern India—the precise opposite of what we have known in the latter part of the twentieth century.

Muslim invasions had started from Ghazni in Afghanistan in the late tenth century. It took three hundred years for the Muslims’ ‘Delhi Sultanate’ to take control of the whole plain from Indus to Ganges, and another century to grasp most of the rest of the subcontinent. Their unity was not sustained, but their presence in India continued to count, especially after 1505, when Babur, leading yet another army down from Afghanistan, founded the Mughal empire.

The incomers were known to the Indians as

Turu ka

ka

(’Turks’). They brought in a new self-confident civilisation that conversed in a form of eastern Turkic (Chagatay), prayed in Arabic, but was literate above all in Persian.

Their cultural self-confidence, their totally alien concepts of decorous behaviour and the point of life, and above all their developed systems of administration conducted in Persian, meant that they had far, far more linguistic effect than the previous, non-doctrinal, incursions from the same direction of the Śaka, Kushāna and Hū a. Now for the first time Sanskrit was supplanted as the elite language of India.

a. Now for the first time Sanskrit was supplanted as the elite language of India.

Ironically, the Muslims’ success in invading the continent was largely a result of their skill with cavalry, and the fine Afghan-bred horses that they brought with them. The distant descendants of the Aryan horse-borne invaders of the second millennium BC had at last been beaten at what had once been their own game.

At about the same time, some of the civilisations of South-East Asia that had been Sanskrit-speaking were taking up the same new religion, but apparently for quite different motives.

There was no military conquest here, nor social revolution in favour of lower castes. Nevertheless, some ports in northern Sumatra became Muslim in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, and Melaka (Malacca), the most important trading centre, situated on the Malay peninsula, embraced Islam some time in the early fifteenth.

*

The religion spread widely among its trading partners, notably to Java, south Sulawesi, the Moluccas and Mindanao. It is presumed that the influence came from Muslim traders out of India, perhaps in a kind of commercial domino effect, with kingdom after kingdom reckoning that they stood to maintain their Indian links only if they took up the faith—or perhaps responding to a desperate Islamic rush to proselytise before the arrival of the Portuguese.

45

Whatever the linkage, the new religion created a new social climate, and put an end to Sanskrit’s reign as the representative language of culture here.