Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (60 page)

Read Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China Online

Authors: Jung Chang

Tags: #History, #General

Earlier that year, Cixi was strolling round in the garden of the Forbidden City, contemplating the many Buddhist statues there. Somehow, she felt the statues were not ideally placed and ordered the eunuchs to rearrange them. As the statues were being moved, a large pile of soil was exposed. With a frown, Cixi ordered the soil to be swept away. Head eunuch Lianying went down on his knees and implored her to leave it untouched. The soil had been there for as long as anyone could remember, and the strange thing about it was that it had remained a neat and tidy pile, with not a speck of earth out of place. Birds, it seemed, had never perched on it and the rats and foxes that prowled the palace grounds had evidently avoided it. Word had been handed down for generations that this was a mound of ‘

magic earth’, there to protect the great dynasty. Cixi was famously superstitious, but she seemed to be annoyed by this explanation and snapped, ‘What magic earth? Sweep it away.’ As the pile of soil was being levelled, she repeatedly murmured to herself, ‘What about this great dynasty? What about this great dynasty?!’ Listening to her, one eunuch said he and his fellow attendants felt sad: it seemed the empress dowager was expecting that the Qing dynasty was nearing its end.

Indeed, Empress Dowager Cixi had foreseen that her reforms, drastically changing China, could in the end bury her own dynasty. As long as she lived, the Manchu throne would be secure. But once she was gone, her successor might not have the same strength, and the constitutional monarchy she had tried to create might come to nothing. Chinese and Western observers were already predicting anti-Manchu uprisings after her death. The fate of the Manchu, her own people, preoccupied the empress dowager in her last hours. If Republican uprisings did inundate the empire, the only option for the vastly outnumbered Manchu would have to be surrender, if a bloodbath was to be avoided. Only surrender could save her people – as well as spare the country civil war. She was quite certain that, faced with Republican uprisings, the men at court would choose to defend the dynasty and fight to the death. No man would counsel surrender, even if he wanted to. This is why Cixi gave the decision-making power in such an ‘exceptionally critical’ crisis to Empress Longyu. Cixi could depend on the empress to surrender the dynasty in order to ensure her own survival, as well as that of the Manchu people. Empress Longyu had lived in surrender all her life. She did not care about humiliation and was the ultimate survivor. As a woman, she was also not required to demonstrate macho bravado.

Cixi’s far sight was borne out exactly three years later, when long-anticipated uprisings and mutinies broke out in 1911. Triggered by a disturbance over the ownership of a railway in Sichuan, and followed by a major mutiny in Wuhan, upheaval spread to a succession of provinces, many of which declared independence from the Qing government. Although these events had no unified leadership, most shared a common goal: to overthrow the Qing dynasty and form a Republic.

fn1

Manchu blood began to flow: the reformist Viceroy Duanfang was murdered, and in Xian, Fuzhou, Hangzhou, Nanjing and other cities Manchu men and women were being slaughtered. The idea of surrender, in the form of abdication by the emperor, was mooted. As Cixi had foreseen, Manchu grandees vehemently resisted, vowing to defend the dynasty to the last man. Again as she had foreseen, the

Regent himself also spoke publicly against abdication, even though privately he was in favour. He knew that it was futile to fight (in spite of the substantial support the court still enjoyed), but he did not want to be the person responsible for his dynasty’s downfall. Cixi’s deathbed decree solved this excruciating dilemma. On 6 December,

Zaifeng resigned his position as Regent and referred all decisions to Empress Longyu. The empress, gathering the grandees around her,

fn2

declared through her tears that she was prepared to take responsibility for ending the dynasty through the abdication of the five-year-old Puyi. ‘

All I desire is peace under Heaven,’ she said.

Thus, on 12 February 1912, Empress Longyu put her name to the

Decree of Abdication, which brought the Great Qing, which had ruled for 268 years, to its end, along with more than 2,000 years of absolute monarchy in China. It was Empress Longyu who decreed: ‘On behalf of the emperor, I transfer the right to rule to the whole country, which will now be a constitutional Republic.’ This ‘Great Republic of China will comprise the entire territory of the Qing empire as inhabited by the five ethnic groups, the Manchu, Han, Mongol, Hui and Tibetan’. She was placed in this historic role by Cixi. Republicanism was not what Empress Dowager Cixi had hoped for, but it was what she would accept, as it shared the same goal as her wished-for parliamentary monarchy: that the future of China belong to the Chinese people.

fn1

Sun Yat-sen, travelling overseas, was not the leader of the uprisings. But he had been the earliest and most persistent promoter of Republicanism and is rightly seen as the ‘father’ of Republican China.

fn2

Viceroy Zhang Zhidong was not among them; he had died in 1909.

Epilogue: China after Empress Dowager Cixi

Empress Dowager Cixi’s legacy was manifold and towering. Most importantly, she brought medieval China into the modern age. Under her leadership the country began to acquire virtually all the attributes of a modern state: railways, electricity, telegraph, telephones, Western medicine, a modern-style army and navy, and modern ways of conducting foreign trade and diplomacy. The restrictive millennium-old educational system was discarded and replaced by Western-style schools and universities. The press blossomed, enjoying a freedom that was unprecedented and arguably unsurpassed since. She unlocked the door to political participation: for the first time in China’s long history, people were to become ‘citizens’. It was Cixi who championed women’s liberation in a culture that had for centuries imposed foot-binding on its female population – a practice to which she put an end. The fact that her last enterprise before an untimely death was to introduce the vote testifies to her courage and vision. Above all, her transformation of China was carried out without her engaging in violence and with relatively little upheaval. Her changes were dramatic and yet gradual, seismic and yet astonishingly bloodless. A consensus-seeker, always willing to work with people of different views, she led by standing on the right side of history.

She was a giant, but not a saint. Being the absolute ruler of one-third of the world’s population and the product of medieval China, she was capable of immense ruthlessness. Her military campaigns to regain Xinjiang and to quell armed rebellions were brutal. Her attempts to use the Boxers to fight invaders resulted in large-scale atrocities by the Boxers.

For all her faults, she was no despot. Compared to that of her predecessors, or successors, Cixi’s rule was benign. In some four decades of absolute power, her political killings – whether just or unjust – which are recorded in this book, were no more than a few dozen, many of them in response to plots to kill her. She was not cruel by nature. As her life was ending, her thoughts were about how best to prevent bloody civil war and massacres of the Manchu people, whose survival she ensured by sacrificing her dynasty.

She also paid a heavy personal price. Cixi was a devout believer in the sanctity of the final resting place, but her own tomb ended up being desecrated. The leaders of the first few Republican administrations, starting with General Yuan (who died in 1916), observed the

agreed terms of the abdication and protected the Qing mausoleums. In 1927, the more radical Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek, drove these men out and established a new regime. A year later, and twenty years after Cixi’s death, an unruly army unit

broke into Cixi’s tomb to plunder the jewels that were known to have been buried with her. Using dynamite, officers and men blasted a breach in the wall and, with bayonets and iron bars, forced open the lid of her coffin. After seizing the jewels around her, they tore off her clothes and pulled out her teeth, in search of any possible hidden treasure. Her corpse was left exposed.

When

Puyi, the last emperor, heard about the sacrilege, he was devastated, as he later described. Now in his twenties, Puyi had been summarily expelled from the Forbidden City in 1924 (which had been a breach of the abdication agreement) and had since been living in Tianjin. He sent members of the former royal family to rebury Cixi’s remains, and protested to the Chiang government. As the robbery became a national scandal, there was an investigation, but it petered out and no one was punished – thanks, it seemed, to handsome bribes all round. When Puyi heard a widely believed rumour that the pearl in Cixi’s mouth had been plucked out and used to decorate Mme Chaing’s shoe, he became filled with bitter hatred. The outrage cemented his resolve to throw in his lot with the Japanese, who made him the Emperor of Manchukuo, the puppet state set up in Manchuria, which they occupied in 1931. Japan then invaded China proper in 1937.

Cixi had struggled to thwart Japan’s attempts to turn China into part of its East Asian empire, and had murdered her adopted son to prevent it. Ironically, if she had delivered China to Japan, it is almost certain that her last resting place – and her remains – would have been respected.

Chiang Kai-shek, a true heir to Cixi, fought Japan throughout the Second World War. The Japanese devastation of Chiang’s state paved the way for Mao to seize power in 1949, although the pivotal role in his rise was played by Stalin, Mao’s sponsor and mentor. While post-war Japan metamorphosed into a flourishing democracy, China was plunged into an unprecedented abyss by Mao’s twenty-seven-year rule, which swallowed the lives of well over seventy million people in peacetime – until his death in 1976 put a stop to his atrocities. For his misrule Mao offered not a word of apology, unlike Cixi, who publicly expressed remorse for the damage she had done – which, though grave, was a fraction of what Mao inflicted on the nation. Pearl Buck, the Nobel Prize-winner for literature, who was born in 1892 and grew up in China when Cixi was in power, and who then lived under, or observed, the subsequent regimes, described in the 1950s ‘how the Chinese whom I knew in my childhood felt about her’: ‘

Her people loved her – not all her people, for the revolutionary, the impatient, hated her heartily . . . But the peasants and the small-town people revered her.’ When they heard she was dead, villagers felt ‘frightened’: ‘“Who will care for us now?” they cried.’ Pearl Buck concluded, ‘This, perhaps, is the final judgment of a ruler.’

The past hundred years have been most unfair to Cixi, who has been deemed either tyrannical and vicious or hopelessly incompetent – or both. Few of her achievements have been recognised and, when they are, the credit is invariably given to the men serving her. This is largely due to a basic handicap: that she was a woman and could only rule in the name of her sons – so her precise role has been little known. In the absence of clear knowledge, rumours have abounded and lies have been invented and believed. As Pearl Buck observed, those who hated her were simply ‘

more articulate than those who loved her’. The political forces that have dominated China since soon after her death have also deliberately reviled her and blacked out her accomplishments – in order to claim that they have saved the country from the mess she left behind.

In terms of groundbreaking achievements, political sincerity and personal courage, Empress Dowager Cixi set a standard that has barely been matched. She brought in modernity to replace decrepitude, poverty, savagery and absolute power, and she introduced hitherto untasted humaneness, open-mindness and freedom. And she had a conscience. Looking back over the many horrific decades after Cixi’s demise, one cannot but admire this amazing stateswoman, flawed though she was.

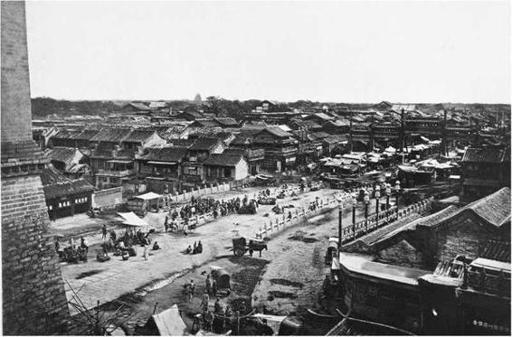

Cixi was a devout Buddhist and revered Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. In 1903, she dressed as Guanyin to have photographs taken; here with the two eunuchs closest to her, Lianying (to her left) and Cui (to her right), in the costumes of characters associated with the Goddess.