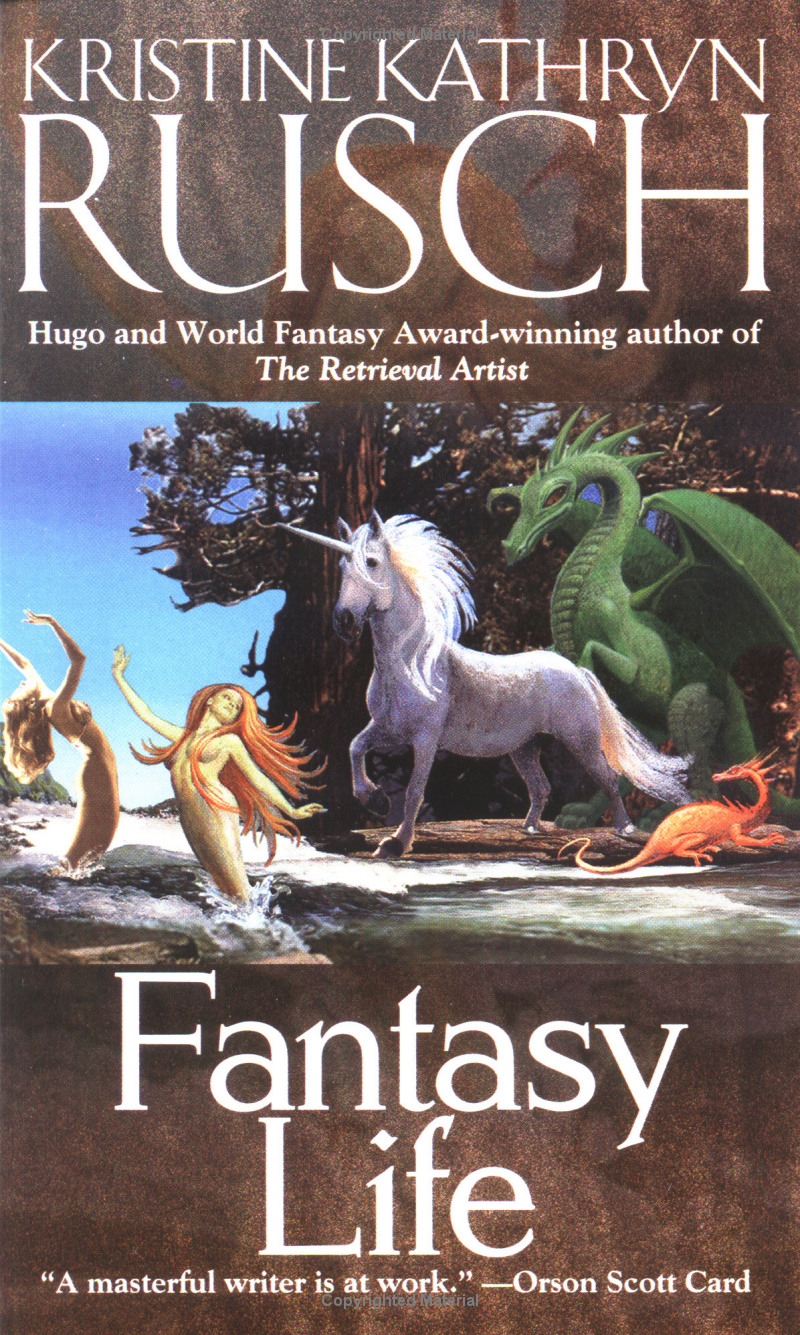

Fantasy Life

Authors: Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Screaming echoed around Emily …

. . . horrifying and deep, screaming like she never heard before. She coughed the water out of her lungs and breathed, and then she turned around, reaching for the dock as she did.

The air was filled with black smoke and an awful rancid burning smell. She could recognize part of the smell—hair burning—but the rest was something she had never encountered before.

The inky blackness poured off the dock and across the lake, engulfing her. She grabbed the ancient wood, then saw through the slats what was burning.

It was Daddy.

She screamed for him, but he didn’t seem to hear her. He was slapping himself and dancing on the top of the dock, trying to put out the fire, which seemed to come from his chest and burn upwards. . . .

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

An

Original

Publication of POCKET BOOKS

| A Pocket Star Book published by |

Copyright © 2003 by White Mist Mountain, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce

this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue

of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 978-1-4516-0599-0

eISBN-13: 978-1-45166-440-9

First Pocket Books printing November 2003

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Cover design by John Vairo, Jr.; front cover illustration by Rowena Morrill

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Dean Wesley Smith with love.

Now you get to say I told you so.

Part 2: The Prodigal Daughter Returns November

Part 6: The Devil and The Deep Blue Sea

Part 8: And a Little Child Shall Lead Them

I owe a great deal of gratitude to a lot of people on this project. Thanks go first and foremost to John Ordover, for pushing me and for tolerating the mystical writer’s talk. Thanks also to Dean, who held me up the whole way. And a great deal of thanks go to John Helfers, Larry Segriff, and Martin H. Greenberg, who got me to write the first stories set in Seavy County.

HE

F

IRST

D

EATH

July

Madison. Wisconsin

On the hottest day of the year, Emily Buckingham—who, until two months before, had been known as Emily Walters—took her bike out of the garage, filled two bottles of water, stuck them in the bottle cages, and dusted off her bike helmet. If she got caught, she would say she was just out for a ride, and she got lost.

Her mom might not believe that, but there’d be no proof. And proof, Emily knew from watching too many cop show reruns while Mommy was teaching summer school, was all that mattered. Mommy could guess all she wanted, but she’d never really know the truth.

Sophia, this week’s baby-sitter, had the radio on really loud in the kitchen. Emily could hear it on the porch of the old house the university rented cheap to needy professors. Emily hated the house. It’d been built by some famous Frank guy who seemed to like sloping windows and lots of stone and sixties crap that Mommy said was expensive but ugly.

Emily thought the whole house was ugly, even the living room, which was supposed to be the centerpiece. The house was so ancient that it didn’t have air-conditioning, and regular air didn’t flow right, so the porch was the only comfortable place in this heat spell.

At lunch—which Emily had to make because Sophia was too wrapped up in some phone conversation with a guy named Jimmy, who’d promised her he’d help with her green cards and her Visa and had somehow gone back on that promise—the

guy on the radio news announced it was ninety-nine degrees with 95 percent humidity, and it was only going to get hotter. He recommended everybody hunker down and stay cool and drink a lot of fluids, which made Emily remember the water bottles, because she would have forgotten otherwise.

After she finished her peanut butter sandwich, she told Sophia she was going outside, but she didn’t say where. Sophia waved at her, probably thinking more about the Visa than about Emily. One thing about Emily, her mom always said, she was a good kid.

And this time, being a good kid was going to work in Emily’s favor.

When she went out into the heat, she almost changed her mind. It felt hotter than ninety-nine degrees with 95 percent humidity. It always felt hotter in this crummy neighborhood so far away from the lake.

Here the houses were crammed together like kids on a bus, and the trees, even though they gave shade, made everything seem even more crowded. The streets were hilly, and Camp Randall Stadium was nearby, which Mommy said would be a really big pain in the fall.

Emily didn’t want to be here in the fall. She didn’t want to be here now, but she didn’t have a lot of choice. Mommy let Daddy have the big house on Lake Mendota in the divorce, kinda like a consolation prize, Mommy said, although having a house didn’t seem like a real consolation to Emily for losing the whole family.

Mommy changed her last name and said Emily had to do the same thing, which Emily hadn’t liked but hadn’t known how to argue. The lawyer lady, who had lots of big teeth and even bigger hair and wore too much perfume, had put a hand on Emily’s shoulder and said,

Trust me, honey, it’s for the best.

But it wasn’t for the best.

People didn’t lose their daddies because “his personality

has changed, sweetheart” and because some judge thought that was a big deal. It wasn’t a big deal. Daddy was still Daddy, he just couldn’t be home as much, and when he was home, he couldn’t spend as much time with her and Mommy.

Then Daddy said that thing no one would say what it was and everything went bad and he got to keep all his family money, which somehow paid for the house, and Mommy got to keep her job and Emily got to keep her clothes and her books and her toys and nothing else, not even her daddy.

And no one asked her what she wanted, not then, and not now. They just figured she’d live with it, because they were.

They figured her wrong.

But then, they always figured her wrong. Emily might have been a good girl, but that was mostly because she was interested in good-girl things. She thought kids who broke the rules at school were stupid because school was interesting and a whole lot better than staying at home by yourself all summer, watching reruns on TV and

Jerry Springer

and this really bad soap opera in Spanish that her other baby-sitter, Inez, liked. Emily was learning Spanish from the show and from Inez, whose English wasn’t too good, but that wasn’t like sitting in class.

Nothing was.

This fall, Emily’d have to go to a whole new school because they lived in this crummy neighborhood now, where there wasn’t a lot of kids and where what kids who lived here were pretty stuck up. Emily had been alone all summer, and reading when she wasn’t watching TV, and thinking a lot about Daddy being alone all summer.

So she came up with the plan.

She had to pick the right day because it would take a long time to ride from Camp Randall to Shorewood. She’d have to stay away from University Avenue because, when it merged with Campus Drive, it got lots of lanes and stoplights and people not

caring who they hit when they went too fast around corners.

Emily figured Old Middleton Road was her best bet, and one afternoon, she got Inez to drive it for her so that she could see it. That worked kinda, although Inez kept telling Mommy that Emily was being weird, wanting to see her old house and everything, even though the house was on the opposite side of University from Old Middleton Road.

Inez wasn’t dumb, which was why Emily had to pick a Sophia day to take the bike.

There weren’t going to be a lot more Sophia days because Mommy didn’t like the mess she left the house in, so on days without Inez, Emily might have to do something lame like day care on campus. The University of Wisconsin sponsored day care for kids all summer long, but the kids who were usually there were little kids, not ten-year-olds. Ten-year-olds were supposed to be at camp or summer school or on vacation, not trying to read while some baby screamed his lungs out.

Emily was going to ask Daddy if he could take her on non-Inez days, even if the judge didn’t like it. Daddy could afford somebody to come in and watch both of them to make sure nothing bad happened, although Emily wasn’t sure what bad stuff could happen around Daddy.

Of course, she hadn’t seen him a lot since his personality changed, but in court, his lawyer said he’d be better if he took drugs. Mommy said the problem was there was no guarantee he’d take the drugs, but Emily thought there was no guarantee that he wouldn’t either.

So when she called this morning and listened to the phone ring, her stomach twisting so much she wasn’t sure her breakfast bar would stay down, and heard Daddy’s familiar deep voice saying, “Hello? Hello? Is anyone there?” she just knew he was taking the drugs and he’d be fine, he’d be the Daddy who told her stories and rode her around on his shoulder and taught her how to ride this very bike.