Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (20 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Example 4.3.

Crown’s theme

Crown’s strength and restless vitality, like those of a caged animal, are evident in the relentless syncopation of his theme. Musically, Crown’s theme is also confined, within the narrow limits of a minor third. Further, in keeping with his dominating presence, whenever Crown appears all other themes are subordinate. His music even dominates the final struggle with Porgy in act III, scene 1, before Porgy states his musical supremacy and manages to overcome and kill his nemesis. In act II, scene 1, however, Crown, who has been absent a month from Catfish Row, does not exert any dramatic influence on the actions or thoughts of Porgy and Bess, and his musical theme is appropriately absent from this peaceful scene.

What about Bess? Does she not merit a theme of her own? Commentators on the opera have without exception neglected to assign her one.

81

Crown’s music dominates his fight to the death with Porgy, but Bess’s musical identity is less assertive and strongly influenced by the man she is with at the time (Porgy, Crown, or Sporting Life). Although Bess certainly holds her own musically, the two songs that she sings to her men, “What You Want

Wid Bess?” (to Crown) and “I Loves You Porgy” (to Porgy) (

Example 4.4

), bear striking melodic or rhythmic resemblances to Porgy’s themes, the former a paraphrase of Porgy’s central theme (

Example 4.1a

) and the latter a new melody that uses the rhythms of “They pass by singin’” (

Example 4.1b

). When she sings “Summertime” to Clara’s orphaned baby in act III, scene 1, Bess demonstrates her hard-won acceptance into the Catfish Row community by singing one of their songs.

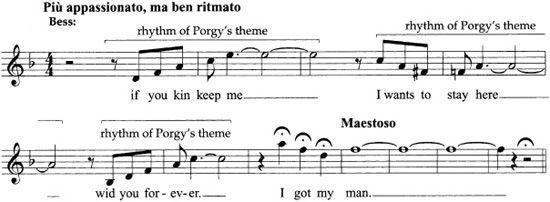

Example 4.4.

“I Loves You Porgy”

It is not surprising, then, that Bess’s weaknesses and chameleon-like nature as a character have caused writers to overlook (with good reason) that Gershwin did in fact associate a specific theme with his heroine, albeit privately and ultimately unrecognizably. We know this only from Heyward’s original libretto typescript, which he sent to Gershwin, where on page 2–17 Gershwin indicated in a handwritten notation that a “Bess theme” should accompany the words sung by Bess, “Porgy, I hates to go an’ leave you all alone.”

82

At this point in the genesis of the work the idea of a love duet between the principals, the future “Bess, You Is My Woman Now”—which does not have a counterpart in the play

Porgy

—may have been an embryo in Gershwin’s mind but it had not yet been hatched.

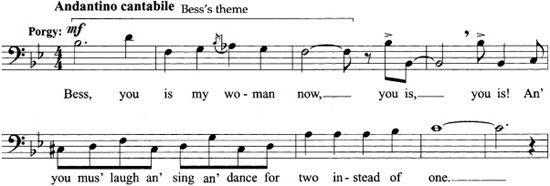

Earlier it was noted that the eventual insertion of “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” was the most substantial alteration to Heyward’s typescript for this scene. Perhaps it is possible to conjecture, after all, even without the benefit of Gershwin’s handwritten notes, that the principal tune of this famous duet (even if Porgy sings it) might belong to Bess (

Example 4.5

).

83

And of course it is reasonable (and egalitarian) that Bess, who is capable at this point in the drama of dispelling Porgy’s loneliness, deserves her own theme, especially since she is deprived of a solo aria in act III, scene 3. Surely it is significant that her opening intervals consists mainly of consonant major thirds and

sixths and that her principal minor third is gently completed by an intervening step, just as Bess fills in the gap of Porgy’s lonely existence. Interestingly, Bess’s theme also figures prominently in the orchestra in the opera’s final scene, act III, scene 3, when Porgy inquires for Bess upon his return from jail and she is not there to sing her theme. In the last moments of the opera Bess’s theme—again presented in the orchestra in her absence—connects with Porgy’s own central theme for the first time to seal their fate.

84

Example 4.5.

Bess’s theme (“Bess, You Is My Woman Now”)

Act II, scene 1, provides abundant evidence of Gershwin’s skill in making dramatic connections and distinctions through his use of musical signatures or leitmotivs. Once he has shown, for example, that Bess’s theme and the Catfish Row songs can at least temporarily transform Porgy’s loneliness into hope, Gershwin’s motivic transformations reveal a great deal about the meaning and significance of future dramatic events. One such scene, act II, scene 3, which takes place one week after Bess left Porgy to join the Catfish Row picnic on Kittiwah Island, offers a particularly vivid demonstration of Gershwin’s ability to establish dramatic meaning through motivic transformation and paraphrase.

For the week that followed Bess’s meeting with Crown on the island in the previous scene (act II, scene 2), Bess was “out of her head” back in Catfish Row. She remains in precarious condition at the opening of scene 3. Before we see Bess, however, we hear Jake’s melody and a reprise of “It Take a Long Pull to Get There.” In a passage cut from the New York production Bess sings “Eighteen mile to Kittiwah, eighteen mile to trabble,” a musical line that might be interpreted as another of the many transformations of Porgy’s central theme. Like Porgy’s theme (

Example 4.1a

), it is encompassed within a perfect fifth and contains a prominent descending minor third (at the end of its second measure). It also reuses the syncopated rhythm of Porgy’s

loneliness (on “trabble”) and combines this rhythm with the half-step interval that dominated the “Buzzard Song” (

Examples 4.1c

and

4.1d

).

Bess’s recitative also shows the influence of Sporting Life with its glaring and ominous augmented fourth (A-D ) (the same sound as the diminished fifth (G-D

) (the same sound as the diminished fifth (G-D ) in

) in

Example 4.2

). When she returns to this phrase moments later with the words, “Oh, there’s a rattle snake in dem bushes,” one can imagine the devilish and serpentine Sporting Life lurking in the bushes as well. After Bess sings this brief passage she collapses and Porgy sings his first words of the scene, “I think dat may-be she goin’ to sleep now,” an easily perceptible transformation of his central theme untarnished by any intrusion of Sporting Life. The devil is taking a nap and Bess will recover.

Serena prays on Bess’s behalf and in answer to these prayers Catfish Row comes back to life with Jake’s theme and the music of street vendors hawking their wares.

85

We know that Bess has recovered when we hear the orchestra play the opening of her theme (unsupported by harmony), and her conversation with Porgy is underscored by the continuation of “Bess, You Is My Woman Now.” In their conversation Porgy tells Bess that he knows she has “been with Crown” on Kittiwah Island, because “Gawd give cripple to understan’ many thing he ain’ give strong men.” Bess, too, understands many things about herself, including the fact that when Crown comes for her, she will be incapable of resisting him. When, near the end of “I Loves You Porgy,” she sings, “If you kin keep me I wants to stay here wid you forever.—/ I got my man” (

Example 4.4

), she uses the rhythm of “They pass by singin’” (

Example 4.1b

) to plead with Porgy to keep her safe from a man who possesses a harmful power over her.

Although Bess survives her illness and is able to express her love for Porgy once again, the moment of hope that concluded “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” has vanished forever (along with the key of F major reserved for their brief moment of bliss). With her realization that the irresistible Crown, who was conspicuously absent in the earlier scene, now represents a menace to her future happiness with Porgy and that she is now unworthy of the man she loves, Bess has been rendered incapable of defusing Porgy’s loneliness. Gershwin conveys this dramatic point simply and effectively when he gives Bess a new melody that is rhythmically identical to Porgy’s loneliness theme. Bess has now become so overwhelmed by Porgy’s loneliness that its rhythm has become a consuming obsession for her as well. She cannot sing anything else, despite Porgy’s assurances of a better life and a sturdy statement of Porgy’s central theme to conclude their duet.

major reserved for their brief moment of bliss). With her realization that the irresistible Crown, who was conspicuously absent in the earlier scene, now represents a menace to her future happiness with Porgy and that she is now unworthy of the man she loves, Bess has been rendered incapable of defusing Porgy’s loneliness. Gershwin conveys this dramatic point simply and effectively when he gives Bess a new melody that is rhythmically identical to Porgy’s loneliness theme. Bess has now become so overwhelmed by Porgy’s loneliness that its rhythm has become a consuming obsession for her as well. She cannot sing anything else, despite Porgy’s assurances of a better life and a sturdy statement of Porgy’s central theme to conclude their duet.

86

Later, in act III, scene 2, Sporting Life mocks the hero (who is about to lose the love of his life) by singing the short-long rhythm of Porgy’s loneliness themes (

Examples 4.1b

and

c

) no less than four times in the first six

measures of his “There’s a Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York.” But it is Bess’s fatalistic sense of defeat in act II, scene 3, rather than Sporting Life’s powers of mockery and seduction that enables us to understand why she is so easily persuaded she belongs in New York rather than in Catfish Row.

We will meet Ira Gershwin again five years after

Porgy and Bess

as Kurt Weill’s lyricist for

Lady in the Dark

(see

chapter 7

). For the first two of these years, George was only able to compose a pair of film scores,

Shall We Dance

(1936) and

A Damsel in Distress

(1937), and start a third,

The Goldwyn Follies

, which was completed by Vernon Duke after Gershwin’s sudden death of a brain tumor in July 1937.

Assessments on the relative merits of Gershwin’s twenty musicals and one opera continue to vary, even among music historians. For example, while H. Wiley Hitchcock concludes that

Porgy and Bess

was “a more pretentious but hardly more artistically successful contribution” than Gershwin’s musical comedies and political satires, Hamm writes unreservedly that Gershwin’s opera “is the greatest nationalistic opera of the century, not only of America but of the world.”

87

Unfortunately, from Gershwin’s time to ours, the comedies and satires have seldom been revived in anything approaching their original state, even though nearly all contain one or more songs of lasting popularity and extraordinary musical, lyrical, and dramatic merit. In contrast, Gershwin’s sole surviving opera, a work that began its career on Broadway, has, despite its pretensions and attendant artistic and political controversies, long since demonstrated a stage worthiness matched only by the memorability of its tunes.