Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (21 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

ON YOUR TOES AND PAL JOEY

Dance Gets into the Act and “Sweet Water from a Foul Well”

T

he historic collaboration of Richard Rodgers (1902–1979) and Lorenz Hart (1895–1943) began inauspiciously, shortly after their first meeting in 1919, when one of their first songs, “Any Old Place with You,” was interpolated into a Broadway show. Hart was twenty-four and Rodgers only seventeen. The next year the new partners produced the first of three varsity shows at Columbia University and placed seven interpolated songs in a modestly successful Sigmund Romberg musical,

The Poor Little Ritz Girl

. After five years of failures and frustrations (Rodgers was on the verge of quitting show business to become a babies’underwear wholesaler), the duo enjoyed two big hits in 1925,

The Garrick Gaieties

, a revue that included among its seven Rodgers and Hart songs the still-popular “Manhattan,” and

Dearest Enemy

, a romantic musical set during the Revolutionary War.

These two shows launched a succession of popularly received musicals, each containing at least one future perennial song favorite:

Peggy-Ann

in 1926 (“Where’s That Rainbow?”),

A Connecticut Yankee

in 1927 (“My Heart Stood Still” and “Thou Swell”),

Present Arms

in 1928 (“You Took Advantage of Me”), and

Evergreen

in 1930 (“Dancing on the Ceiling”). In 1930 the pair began a five-year sojourn in Hollywood where they produced the much discussed but still relatively unknown

Love Me Tonight

(1932), directed by Rouben Mamoulian, the future stage director of

Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma!

, and

Carousel

. A circus musical spectacular,

Jumbo

, marked their return to Broadway in 1935 and the beginning of their greatest successes:

On Your Toes

(1936),

I’d Rather Be Right

and

Babes in Arms

(1937),

I Married an Angel

and

The Boys from Syracuse

(1938),

Pal Joey

(1940),

By Jupiter

(1942), and a revised

A Connecticut Yankee

(1943).

Before the belated triumphs of 1925, Rodgers, who like Hart had dropped out of Columbia University without earning a degree, decided at the age of twenty that he needed to acquire a more rigorous musical education. As an adolescent Rodgers had received informal instruction both from his mother, an amateur pianist, and from his father, an enthusiastic amateur singer. Over three academic years, 1920–21, 1921–22, and 1923–24, he studied piano, theory, and ear training, including a special harmony class limited to five students with the noted theorist and author Percy Goetschius his final year at the Institute of Musical Art (which became the Juilliard School of Music in 1926).

Complementing this musical training was a legendary facility in the creation of melody. Rodgers’s early biographer David Ewen reports that after Hammerstein had labored many hours and sometimes weeks, Rodgers needed only about twenty minutes to compose “June Is Bustin’ Out All Over” and another twenty minutes for “Happy Talk”; the complex “Soliloquy” from

Carousel

allegedly occupied “about three hours.”

1

Although in his autobiography,

Musical Stages

, Rodgers emphasizes the months of pre-compositional discussions with Hammerstein rather than his own speed, he corroborates the story that “Bali Ha’i” “couldn’t have taken more than five minutes.”

2

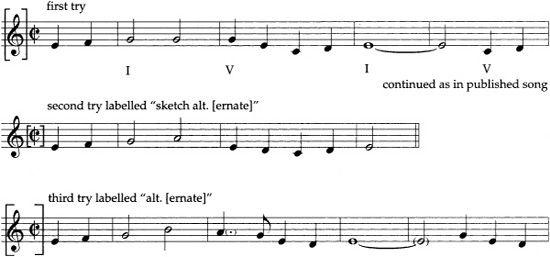

It therefore comes as something of a shock, and perhaps a relief, that the opening of the chorus to “I Could Write a Book” in

Pal Joey

took Rodgers the three tries illustrated in

Example 5.1

before he found a version that satisfied him.

Example 5.1.

“I Could Write a Book,” three sketches for the opening four measures

Throughout his long career Rodgers placed innovation and integration among his loftiest goals for a musical. In

Musical Stages

he writes with pride that

Dearest Enemy

(1925), his first book musical with Hart, gave his team the welcome “chance to demonstrate what we could do with a score that had at least some relevance to the mood, characters and situations found in a story.”

3

Rodgers took similar pride the following year in

Peggy-Ann

’s distinction as the first musical comedy to express Freud’s theories on the stage “by dealing with subconscious fears and fantasies.”

4

Rodgers prefaces his remarks concerning the ill-fated musical about castration,

Chee-Chee

, a musical that received an all-time Rodgers and Hart low of thirty-one performances in 1928, with the suggestion that long before

Pal Joey

(1940) and

Oklahoma!

(1943), Rodgers with Hart “had long been firm believers in the close unity of song and story.”

5

Chee-Chee

provided their first opportunity “to put our theories into practice,” as Rodgers explains:

On Your ToesTo avoid the eternal problem of the story coming to a halt as the songs take over, we decided to use a number of short pieces of from four to sixteen bars each, with no more than six songs of traditional form and length in the entire scene. In this way the music would be an essential part of the structure of the story rather than an appendage to the action. The concept was so unusual, in fact, that we even called attention to it with the following notice in the program:

NOTE:

The musical numbers, some of them very short, are so interwoven with the story that it would be confusing for the audience to peruse a complete list.

6

By the time Rodgers and Hart returned from Hollywood in 1935, their desire to create innovative musicals reached a new level. One year later they wrote

On Your Toes

. The genesis of the show can be traced to the Hollywood years, however, when Rodgers and Hart conceived the idea of a movie musical about a vaudeville hoofer (to be played by Fred Astaire) who becomes involved with a Russian ballet company.

7

Astaire, then busy with his series of films with Ginger Rogers, declined the role and Hollywood rejected their scenario. Soon, however, Broadway bought the idea as a vehicle for a new dancing sensation, Ray Bolger, the scarecrow in Hollywood’s

The Wizard of Oz

in 1939, and the star of Rodgers and Hart’s final Broadway show,

By Jupiter

, in 1942 and Frank Loesser’s first Broadway triumph,

Where’s Charley

? in 1948. Boston tryouts took place between March 21 and April 8, 1936, and

On Your Toes

opened at the Imperial Theatre three days later. When it concluded its run at the Majestic Theatre the following January 23, the hit show had been performed 315 times.

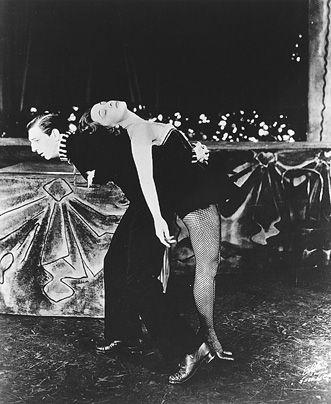

On Your Toes

. Ray Bolger and Tamara Geva (1936). Photograph: White Studio. Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

The history of

On Your Toes

after its initial critically and popularly acclaimed run differs markedly from the history of its more popular predecessor, Porter’s

Anything Goes

(discussed in

chapter 3

). The first major revival of

Anything Goes

in 1962 offered a new book and many interpolated songs, and made a respectable Off-Broadway run of 239 performances; the first revival of

On Your Toes

in 1954, with one interpolation and several other modest alterations, folded after only sixty-four showings. More incriminatingly, the work itself, not the production, was considered the principal reason for its failure.

In 1936 Brooks Atkinson had written that “if the word ‘sophisticated’ is not too unpalatable, let it serve as a description of the mocking book which Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart and George Abbott have scribbled.”

8

By 1954, the

integrated musicals of Rodgers and Hammerstein and even Rodgers and Hart’s recently revived

Pal Joey

—which Atkinson had reviewed disparagingly in 1940 before extolling its virtues in 1952—had created new criteria that musicals such as

On Your Toes

did not match. Thus eighteen years after his initially positive assessment Atkinson attacked as “labored, mechanical and verbose” the book he formerly had deemed sophisticated. For Atkinson and his public “the mood of the day,” which had recently caught up to

Pal Joey

, had “passed beyond”

On Your Toes

. The “long and enervating” road to the still-worthy “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” ballet at the end of the second act simply was not worth the wait.

9

In the 1936

On Your Toes

Rodgers and Hart attempted an integration of music and drama that went beyond their successful innovations in

Peggy-Ann

and their unsuccessful ones in

Chee-Chee

. In

Musical Stages

Rodgers discusses his ambitious new artistic intentions:

One of the great innovations of

On Your Toes

, the angle that had initially made us think of it as a vehicle for Fred Astaire, was that for the first time ballet was being incorporated into a musical-comedy book. To be sure, Albertina Rasch had made a specialty of creating Broadway ballets [for example,

The Band Wagon

of 1931], but these were usually in revues and were not part of a story line. We made our main ballet [“Slaughter on Tenth Avenue”] an integral part of the action; without it, there was no conclusion to our story.

10

Despite such claims, the degree to which co-authors Rodgers and Hart and Abbott succeeded in their attempt to integrate dance, especially “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” has been questioned by Ethan Mordden:

Much has been made of “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue”’s importance as a book-integrated ballet, but it was, in fact, a ballet-within-a-play …

not

a part of the story told in choreographic terms. Only towards the ballet’s end did plot collide with set piece when the hoofer learned that two gangsters were planning to gun him down from a box in the theatre at the end of the number. Exhausted, terrified, he must keep dancing to save his life until help comes, and thus a ballet sequence in

On Your Toes

turned into the

On Your Toes

plot.

11

Mordden’s challenge does not obscure the fact that

On Your Toes

treats a vexing artistic issue: the conflict and reconciliation between classical and popular art. Much of the plot and the comedy in

On Your Toes

evolves from the tensions between the cultivated and the vernacular, between highbrow and lowbrow art. Even the barest outlines of the scenario reveal this.

When in act I, scene 3, we meet Phil Dolan III (“Junior”) as an adult, he is employed as a music professor at a W.P.A. [Work Projects Administration] Extension University, having renounced his career as a famous vaudeville hoofer sixteen years earlier at the insistence of his parents (scenes 1 and 2). His student and eventual romantic partner, Frankie Frayne, writes “cheap” (1936) or “derivative” (1983) popular songs, including “It’s Got to Be Love,” “On Your Toes,” and “Glad to Be Unhappy”; another student, Sidney Cohn, who supposedly possesses greater talent (to match his pretensions and ambition), has composed “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” which will be performed by the Russian Ballet in act II.

The Cat and the Fiddle

, a 1931 hit with lyrics by Otto Harbach and music by Kern, had explored the tensions and eventual accommodation of classical and popular music in a European setting in which a “serious” Romanian male composer and a jazzy American female composer—at the beginning of the show she is already well known as the composer of “She Didn’t Say Yes”—eventually produce a harmonious hybrid.

On Your Toes

contrasted the cultivated and vernacular traditions through dance, two full-length ballets, both choreographed by the revered George Balanchine (1904–1983), who in the previous decade starred in Diaghilev’s ballet company: a classical ballet to conclude act I (“La Princesse Zenobia”) and a jazz ballet (“Slaughter on Tenth Avenue”) as a climax for act II. In the title song, tap dancing and classical ballet alternate and compete for audience approbation in the same number. Further, the Russian prima ballerina (Vera Baranova) and her partner (Konstantine Morrosine) have important dramatic (albeit non-singing) parts as well as their star dance turns. By contrast, in the dream ballet that concludes act I of

Oklahoma!

—the musical which almost invariably receives the credit for integrating dance into the book—the dancing roles of Laurey and Curley are played by separate and mute dancers.