Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (72 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

Like

West Side Story

, the score of

Sweeney Todd

demonstrates impressively intricate musical connections that are dramatically meaningful. Although he acknowledged some indecision about the conclusion of the work, the idea that major characters would be given distinctive themes and the decision to have these themes “collide in the end” was present almost from conception. This is how Sondheim explained his procedure: “I determined that it would be fun for

Sweeney Todd

to start each character with a specific musical theme and develop all that character’s music out of that theme, so that each song would depend in the true sense of the word on the last one. Sweeney’s opening scene dictates his next song, and so on. It’s a handy compositional principle, and it seemed to me that it would pay off very nicely at the end.”

49

In order to understand how this compositional principle works it is necessary to introduce the Gregorian chant

Dies irae

(literally the Latin for “Day of Wrath” and more conventionally Judgment Day), a thirteenth-century text and melody that became officially incorporated into the Catholic Requiem Mass, the mass for the dead, by the sixteenth century. It is this chant that Sondheim chose as the starting point for Sweeney’s theme and for the opening choral number, “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd,” sung by a chorus to help the audience “attend the tale of Sweeney Todd” and reprised to introduce various episodes throughout the story. With its connections to death and the

Last Judgment and its musical resonances, the theme has been especially favored in the last two hundred years from Berlioz to Rachmaninoff. It was an inspired choice to serve as the embodiment of a character who by the end of the first act “Epiphany” will take it upon himself to impart his demented vengeful judgment on the world. On the stage, “Epiphany” provided an opportunity for Sweeney to break the fourth wall and invites the audience to “Come and visit your good friend Sweeney” and to get a shave and “welcome to the grave.” The Sweeney in Burton’s film extends this idea and, in a fantasy sequence, leaves his shop, roams the streets like a ghost visible only to the audience, and invites unaware passersby to get their shaves and his vengeance.

Sondheim explained why he chose the chant and offers information about how he used it: “I always found the Dies Irae moving and scary at the same time,” says Sondheim. “One song, ‘My Friends,’ was influenced by it … it was the inversion of the opening of the Dies Irae. And although it was never actually quoted in the show, the first release of ‘The Ballad of Sweeney Todd’ was a sequence of the Dies Irae—up a third, which changed the harmonic relationship of the melodic notes to each other.”

50

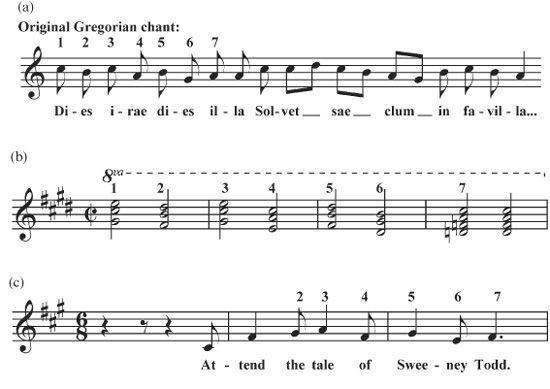

The following set of examples (see

Example 15.1

on the next page) begins with the opening of the

Dies irae

chant, continues with various transformations of the chant’s opening in

Sweeney Todd

(mainly its first seven notes), and concludes with a famous use of the work in the classical literature and a possible earlier allusion by Sondheim himself.

Although Sondheim states he did not quote

Dies irae

(15.1a) literally in

Sweeney Todd

, the published score offers just such a quotation on its second page in the Prelude (15.1b).

51

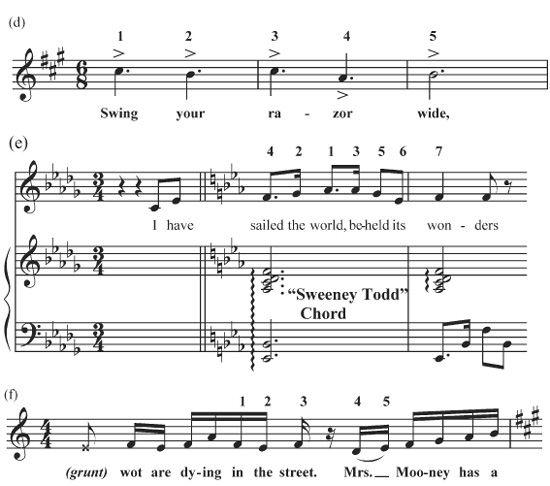

Probably the most prominent and most recurring reference to

Dies irae

is the paraphrase of the chant that marks the opening of “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd,” which includes notes 2–7 of the chant (15.1c). Interestingly, the jig-like rhythm of this paraphrase is reminiscent of the melodically more literal rhythmic and major mode transformation of the chant in the “Dream of the Witches Sabbath” movement of Berlioz’s famous

Symphonie fantastique

of 1830 (15.1 h). The longer and more chant-like notes (the first five notes) at the portion of “The Ballad” shown in

Example 15.1d

described by Sondheim are offset by some pitch alterations to create another major mode variation on the tune. Anthony’s paraphrase of the tune (including some changes in the note order in the first four notes of the chant) in “No Place Like London” (15.1e) adds harmonic density by placing the

Dies irae

in F minor against E in the bass (plus two non-chord tones B

in the bass (plus two non-chord tones B and D), to create an enriched variant of the “Sweeney Todd” chord (a minor seventh with the seventh in the bass or in this case E

and D), to create an enriched variant of the “Sweeney Todd” chord (a minor seventh with the seventh in the bass or in this case E -F-A

-F-A -C).

-C).

Example 15.1

.

Dies irae

and

Sweeney Todd

(a)

Dies irae

original chant (beginning)

(b) First reference of the

Dies irae

in

Sweeney Todd

Prelude (first seven chant notes)

(c)

Dies irae

paraphrased in the opening of “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd” (notes 2 through 7 of the chant)

(d) “Sequence of the Dies Irae—up a third” described by Sondheim in “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd” (first five chant notes)

(e)

Dies irae

paraphrased in “No Place Like London (first four chant notes rearranged as notes 4, 2, 1, and 3 with notes 5-7 in original order and all seven notes harmonized with the “Sweeney Todd” chord)

(f) Fleeting allusion to

Dies irae

in “The Worst Pies in London” (first five chant notes)

(g)

Dies irae

in “My Friends” (first four chant notes first inverted and then in their original order)

(h)

Dies irae

in Berlioz’s

Symphonie fantastique

(quotation and transformation, first seven chant notes)

(i) Possible allusion to

Dies irae

in the “The Miller’s Son” from

A Little Night Music

(first five chant notes with an added note between notes 4 and 5)

The

Dies irae

does not appear directly in the music of the Beggar Woman (Sweeney’s wife Lucy) but nevertheless provides its foundation. In particular, the half step descent on the first two notes of the chant appears prominently in her recurring lament (“Alms … alms … for a mis’rable woman”). In “Epiphany” the descending half step will launch a scalar series of four notes starting with the musical phrase that begins “never see Johanna” and repeated obsessively with new words for the rest of the song. It is possible Sondheim realized that the descending four-note scalar figure, a ubiquitous motive that goes back at least as far as John Dowland’s song “Flow My Tears” in the early seventeenth century, has become a traditional musical sign of lament and mourning. In any case, this is how Sondheim used this simple but powerful figure in “Epiphany” and later when Sweeney mourns his Lucy’s death in the Final Scene. Although the musical connection between the

Dies irae

with Mrs. Lovett is present (in the midst of “The Worst Pies in London” for the first notes of the chant), the chant reference occurs so fleetingly it is barely audible and may be more imagined than real (15.1f).

Example 15.1g

shows how the first four notes of “My Friends” inverts the opening notes of

Dies irae

as Sondheim noted when describing his use of the chant (in the second phrase of the song, the first four notes of the chant appear in their original order). The remaining excerpts demonstrate how Berlioz famously reused the

Dies irae

in his

Symphonie fantastique

(15.1h) and how Sondheim might have previously incorporated the chant in the music he gave Petra to sing in the defiant recurring faster section of

Night Music

’s “The Miller’s Son” (15.1i). If the allusion is intentional in the earlier musical, the point might be considered ironic in that this young sensual character seems so non-judgmental and full of life. On the other hand, the irony is tempered by the fact that Petra points out in her song that life is brief and moments of joy are fleeting.