Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (70 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

In “Theater Lyrics” Sondheim describes this song as a “woman’s lie to her former lover” (Ben), but it may also be interpreted as her lie to the man she married (Buddy), a man who loves her deeply and who provides a steady but boring static grounding, both psychological and harmonic. For Sondheim, the song’s subtext is Sally’s anger at being rejected by Ben many years ago, a subtext that is not found explicitly in either the lyrics or implied by the melody or harmony. Sondheim credits and praises Jonathan Tunick, his principal orchestrator for more than the thirty years between

Company

and

Road Show

, who demonstrated his understanding of the subtext of this song by assigning the “dry” woodwinds to Sally’s wry references about Buddy, and warm strings for the self-referential parts of the text, Sondheim perhaps gives too much credit to Tunick. Even without this orchestral subtlety, which Sondheim describes as analogous to the details in the head of the Statue of Liberty that so impressed Hammerstein, it is arguable that Sondheim’s own subtle musical distinctions between the harmonically synchronized repetitive rhythmic pattern that accompanies the melodic mantra “in Buddy’s eyes” and the more varied contrasting musical phrases when she refers to herself (but still in Buddy’s eyes) would emerge with comparable clarity even in a piano-vocal reduction.

One last mentor, one not cited in “Theater Lyrics,” needs to be mentioned: the composer and mathematician Milton Babbitt. Babbitt’s mentoring began several years after Hammerstein’s initial tutelage when Sondheim, who had majored in mathematics as well as music at Williams College, elected to use his Hutchinson Prize money to study principles of composition and analyze popular songs such as Jerome Kern’s “All the Things You Are” with the illustrious Princeton music theory and composition professor and avant-garde composer, who also was knowledgeable about jazz and loved musicals (he even tried his hand at writing a musical score once and published some of the resulting theater songs).

26

At the same time he was teaching Sondheim traditional classical and popular musical forms, Babbitt was pioneering a new composition technique widely known as “total serialization” as well as

complex electronic works. Babbitt has stated that he did not ask Sondheim to work within this modernist idiom because he did not consider it appropriate to his student’s aesthetic aims. But is it not possible that Sondheim chose Babbitt as a postgraduate compositional mentor at least partly because of his gathering reputation as a mathematically adept modernist? While thirty years earlier Schoenberg systematically arranged pitch according to various permutations of a twelve-tone series in his quest to systematically avoid a tonal center, Babbitt less systemically serialized other parameters as well, including rhythm and tone color.

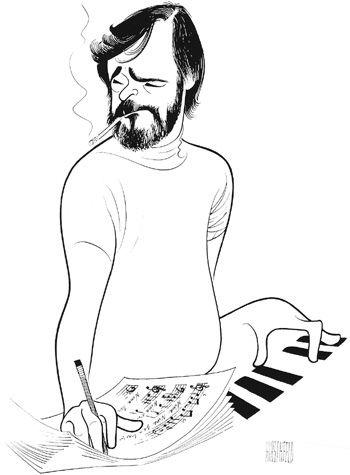

Stephen Sondheim. © AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, the MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK.

WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

It is possible to make the analogy between Babbitt’s allegedly “total” serialization and Sondheim’s allegedly “modernist” musicals, aided and abetted by extraordinarily thoughtful and creative choreographers, directors, scene designers, and orchestrators, which really expand upon, rather than discard, the traditions established by earlier acknowledged masterpieces. Like Babbitt, who only seemed to break with the past while really extending Schoenberg’s aesthetics as well as his methods, Sondheim expanded on the insights and achievement of Hammerstein and other predecessors in what had become, by the 1950s, a great American musical tradition. Following the example of his theatrical mentors, Hammerstein, Shevelove, and Laurents, the revolutionary traditionalist Sondheim would continue to probe into the nuances of his complex characters and the meaning of his dramatic subjects, achieving moments of moving emotional directness as well as dazzling verbal and artistic pyrotechnics.

Sweeney Todd

While the so-called integrated musical remained very much alive after

West Side Story

, the next step in dramatic organicism, the so-called concept musical, where “all elements of the musical, thematic and presentational, are integrated to suggest a central theatrical image or idea,” began to receive notoriety in the 1960s and 1970s.

27

Sondheim and his collaborators, especially Jerome Robbins, Michael Bennett, Harold Prince, Boris Aronson, who designed the first four Prince-Sondheim collaborations with striking originality, and several excellent librettists (George Furth, James Goldman, John Weidman, and Hugh Wheeler), were in the forefront of this development. Musicals based more on themes than on narrative action were no more new in the 1960s than the integrated musicals were in the 1940s. Nevertheless, earlier concept musicals, for example, the revue

As Thousands Cheer

in 1933 (arguably all revues are concept musicals), book musicals such as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Allegro

(1947), or Kurt Weill and Alan Jay Lerner’s

Love Life

(1948)—like the precociously integrated

Show Boat

and

Porgy and Bess

explored in the present survey—deviate from what Max Weber or Carl Dahlhaus would call an “ideal type.”

28

In any event, the pioneering concept musicals of the late 1940s,

Allegro

and

Love Life

, failed to inspire a flock of popularly successful followers. In the 1970s, Sondheim and his collaborators were clearly critically central Broadway figures, even though they garnered only relatively limited live audiences, while more popular artists such as Andrew Lloyd Webber or Stephen Schwartz were marginalized and criticized, probably unfairly, for their alleged aesthetic vacuities.

Perhaps more than any single individual, the inspiration in the move toward the concept musical ideal was Robbins, who early in his career had established thematic meaning through movement and dance as the choreographer of

The King and I

(1951) and as the director-choreographer for Sondheim’s first Broadway efforts,

West Side Story

and

Gypsy

. Robbins was notorious for relentlessly asking, “What is this show about?,” a question that led to the late (and uncredited) insertion of “Comedy Tonight” in

Forum

to inform audiences and prepare them for what they might expect in the course of the evening. Robbins’s insistence on getting an answer to this probing question soon led to the show-opener “Tradition” in

Fiddler on the Roof

(1964), a song that embodied an overriding idea (rather than an action) that could unify and conceptualize a show.

After

Fiddler

, the concept musical was principally championed by Prince (b. 1928–), who had co-produced two of the above-mentioned Robbins shows (

West Side Story

and

Fiddler

). Prince also directed and produced John Kander and Fred Ebb’s

Cabaret, Zorbá

, the considerably altered 1974 hit revival of Bernstein’s

Candide

, and produced the first four of the six Sondheim shows he directed from

Company

in 1970 to

Merrily We Roll Along

in 1981.

29

While producing or co-producing such major hits as

The Pajama Game, Damn Yankees, West Side Story, Fiorello!

, and, with Sondheim,

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

(with Sondheim), and

Fiddler on the Roof

between 1953 and 1964, Prince came into his own as a producer-director with Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick’s

She Loves Me

(1963). The use of a German cabaret as a metaphor for pre–World War II German decadence in

Cabaret

exemplifies Prince’s continuation of the concept idea developed by Robbins.

Arguably, the Sondheim-Prince standard of the concept musical—in the absence of a more meaningful term—throughout the 1970s, with the non-linear

Company

as its iconic exemplar, was in the end, like most of Sondheim’s work with other collaborators, less a revolution than a reinterpretation of the integrated musical.

30

In line with high-modernist aestheticism, narrative structures became more avowedly experimental in the Robbins-Sondheim-Prince “concept” era, and ambitious attempts to expand the expressive scope of the musical were also in vogue. Open appeals to a broad audience Lloyd Webber-Schwartz style, perhaps borrowed from rock, were as critically suspect as a pop song by Babbitt might have been in the same era. Nevertheless, at least one influential director, Prince, managed to navigate through the treacherous shores of the Broadway aesthetic divide.

During the Sondheim years Prince also collaborated with the man this volume has singled out in its Epilogue as the

other

major Broadway composer who flourished from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s, Lloyd Webber (see

chapter 16

). In a dazzling display of Prince’s versatility, the Lloyd

Webber-Prince collaboration,

Evita

, appeared only a few months after

Sweeney

. In addition to his work with Sondheim, Bernstein, Kander and Ebb, and Lloyd Webber, Prince during these years managed to direct

On the Twentieth Century

with yet another composer, Cy Coleman (with the legendary librettist-lyricists Comden and Green). Coleman was another distinguished composer with a long career that flourished during the Sondheim-Lloyd Webber era in musicals from

Wildcat

and

Sweet Charity

in the 1960s to

City of Angels, Will Rogers Follies

, and

The Life

in the late 1980s and 1990s. By the later 1990s, Prince had received more Tony Awards, twenty-one, than anyone since the awards were established in the later 1940s. Of these, no less than eight were bestowed in his capacity as director:

Cabaret, Company, Follies

(shared with Michael Bennett), the

Candide

revival of 1974,

Sweeney Todd, Evita, Phantom of the Opera

, and the

Show Boat

revival of 1994. The quantity and range of Prince’s achievement is nothing short of staggering. This chapter will focus on selected moments in the historic collaboration between Prince and Sondheim.

Although Prince and Sondheim had been friends since 1949—according to Prince’s recollection they met on the opening night of

South Pacific

—and Prince had co-produced

West Side Story

and produced

Forum, Company

was the first of the six Sondheim productions he either directed, or in the case of

Follies

, co-directed (with Bennett). These six shows,

Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd

, and

Merrily We Roll Along

, form a remarkable group. We have already noted the historical and artistic significance assigned to

Company

and an example of subtext in

Follies

.

Each musical in the first trilogy of Sondheim-Prince shows,

Company, Follies

, and

A Little Night Music

, earned Sondheim Tony and Drama Critics Circle Awards for best score. This was a major critical achievement, if not always a financial one.

Company

and

Night Music

earned some profit despite relatively modest runs, 706 and 601 performances and profits of $56,000 and $97,500 respectively, while the more lavish

Follies

lost $665,000 of its $700,000 investment during its 522 performance run.

31

As a tie-in with the “nostalgia” revival along with the more successful revival of Vincent Youmans’s

No, No, Nanette

(1925) in 1971,

Follies

even appeared on the cover of

Time

magazine.

32

Only

Night Music

, however, was spared the criticism that Sondheim was destined to share with another early twentieth-century modernist, Igor Stravinsky, who was also, unfairly, accused of cynicism, coldness, and “bloodlessness.” In the waning days of high modernism, Sondheim was neither high nor low, but somewhere in between. Thus he suffered from some critics’ binary high/low expectations. Like Stravinsky in his early Ballet Russe period (

Firebird, Petrushka, Rite of Spring

), Sondheim was delightfully novel for some in the audience, and yet still not too cerebral and difficult (at least

some of the time) for the mass of musical theatergoers with more traditional expectations of a diverting night out with a happy ending.

The career of Sondheim marks, perhaps for the first time, not only the consistent failure of a composer of the most highly regarded musicals of his generation to produce blockbusters on Broadway, but even major song hits (

Night Music

’s “Send in the Clowns” is the exception that proves the rule).

33

Pacific Overtures

, competing in the same season as

A Chorus Line

and

Chicago

, lost its entire investment as well as most of the Tonys.

Sweeney Todd

, which lost about half of its million dollar investment, received more than half of the major Tony awards, including those for best actor (Len Cariou), actress (Angela Lansbury), director (Prince), scenic design (Eugene Lee), costume design (Franne Lee), book (Wheeler), best score (Sondheim), and best show.