Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (33 page)

Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

STIR-FRIED OYSTER AND SHIITAKE MUSHROOMS WITH GARLIC

SU CHAO SHUANG GU

素炒雙菇

Stir-fried mushrooms with garlic and spring onion are one of the dishes I most frequently cook: this simple method seems to produce a dish that is delicious out of all proportion to its ingredients. You can use any mixture of mushrooms you like, or indeed a single variety—button and enoki mushrooms are also very good—but I find oyster and shiitake a particularly happy combination.

Lard or chicken fat adds another, irresistible dimension (use lard instead of regular cooking oil, or add a spoonful of chicken fat towards the end of cooking to intensify the flavors of the mushrooms). Sometimes I’ll use goose fat if I have some, or add a little of the fat that has solidified at the top of a potful of

Red-braised Pork

. And don’t throw away the layer of fat that solidifies in a roast chicken pan or at the top of a stock; it keeps well in the refrigerator and is a perfect addition to stir-fried mushrooms.

10 oz (275g) oyster mushrooms

5 oz (150g) fresh shiitake mushrooms

2–3 tbsp cooking oil or lard

3 garlic cloves, sliced

¾ cup (200ml) chicken stock

Salt

2 spring onions, green parts only, finely sliced

Clean the oyster mushrooms if necessary and tear or cut lengthways into bite-sized pieces. Trim off and discard the shiitake stalks and slice their caps.

Heat the wok over a high flame. Add the oil or lard and swirl it around before adding the garlic, which should be stir-fried very briefly until you can smell its fragrance. Then add the mushrooms and stir-fry for a couple of minutes until they have somewhat reduced in volume. Then pour in the stock and bring to a boil. Continue to stir until the mushrooms are tender and the stock has been largely absorbed, adding salt to taste. Then add the spring onions, stir a few times so they feel the lick of heat, then serve.

STIR-FRIED OYSTER MUSHROOMS WITH CHICKEN

PING GU JI PIAN

平菇雞片

This gentle, understated dish was one I often enjoyed at a small restaurant near Sichuan University. The subtle savoriness of the chicken marries beautifully with the mushrooms and garlic. You don’t need much chicken, actually: just half a breast would be enough to make the dish. And lard, if you have it, will magically enhance the flavors.

1 chicken breast, without skin (5 oz/150g)

1 spring onion

7 oz (200g) oyster mushrooms

3 tbsp cooking oil or lard

A piece of ginger, about the size of a large clove of garlic, peeled and sliced

2 garlic cloves, sliced

Salt

Ground white pepper

For the marinade

½ tsp salt

1 tsp Shaoxing wine

1 tsp potato flour

Lay the chicken breast on a chopping board and, holding your knife at a right angle to the board, cut it into thin slices. Place in a bowl. Add the marinade ingredients with 2 tsp cold water and mix well.

Holding your knife at a steep angle, cut the spring onion into ⅜ in (1cm) diagonal “horse-ear” slices, keeping the white and green parts separate. Clean the oyster mushrooms if necessary and tear or cut lengthways into bite-sized pieces, discarding any hard bits at the base of their stalks.

Heat a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add 1 tbsp of the oil or lard, swirl it around, then add the mushrooms and stir-fry for a couple of minutes until nearly cooked. Set aside.

Reheat the wok over a high flame, then add the remaining oil and swirl it around. Add the chicken and stir-fry to separate the slices. When the slices are separating but still pinkish, add the ginger, garlic and spring onion whites and continue to stir for a few moments until you can smell their fragrances. Then return the mushrooms and stir to incorporate, adding salt and pepper to taste. Finally, stir in the spring onion greens, then serve.

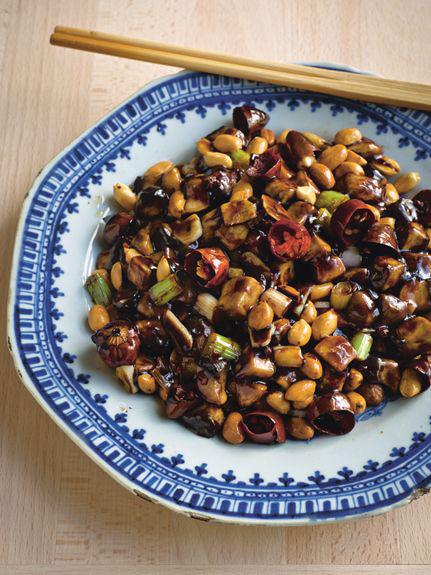

VEGETARIAN “GONG BAO CHICKEN”

GONG BAO JI DING (SU)

宮保雞丁

At the Baoguang Temple, an hour away from Chengdu, if you walk through the grand courtyard just within the entrance gates, past the racks of burning incense and candles and slip off to the right, past the tea house garden with its shady trees and bamboo chairs, you’ll find another, smaller courtyard. At the far side of this are a few tables and chairs and a hatch, hung with wooden slats bearing the names of classic Sichuanese dishes. There is twice-cooked pork, dry-fried eels, crispy-skin fish and even shark’s fin but, because this is a Buddhist monastery, none of them contain any meat or fish at all. The restaurant at the Baoguang Temple is one of the best exponents I know of the Buddhist vegetarian style of cooking, where vegetable ingredients are cunningly engineered to mimic the appearance, aromas and tastes of meat. The “eel” is made from dried shiitakes; the “fish” from mashed potato in tofu skin.

This recipe, in which meaty portobello mushrooms take the place of chicken, is in the same style, although it does include the garlic and onion that are frowned on in monasteries, so it’s not strictly Buddhist. It takes a little time to make, but it’s worth it because, frankly, everyone should have the chance to taste Gong Bao chicken, even vegetarians.

3 large portobello mushrooms (11 oz/300g)

8–10 Sichuanese dried chillies

3 garlic cloves

An equivalent amount of ginger

5 spring onions, white parts only

About ¾ cup (200ml) cooking oil

1 tsp whole Sichuan pepper

3 oz (75g) roasted peanuts

For the marinade

¼ tsp salt

1½ tbsp potato flour

For the sauce

3 tsp sugar

⅛ tsp salt

¼ tsp potato flour

½ tsp dark soy sauce

2 tsp light soy sauce

3 tsp Chinkiang vinegar

Bring a panful of water (about 2 quarts/2 liters) to a boil. Trim the mushrooms and cut into ⅜–¾ in (1–2cm) cubes. Blanch the mushroom cubes in the boiling water for about a minute, until partially cooked. Drain, refresh under the cold tap and shake dry. Add the marinade ingredients and mix well.

Cut the chillies in half and shake out and discard the seeds as far as possible. Peel and thinly slice the garlic and ginger. Cut the spring onion whites into ⅜ in (1cm) sections. Combine the sauce ingredients in a small bowl with 1 tbsp water and mix well.

Heat the oil in a seasoned wok to about 300°F (150°C). At this temperature, you should see small movements in the oil and the surface will tremble slightly. Add the mushrooms and fry for 30–60 seconds until glossy, stirring gently. Remove with a slotted spoon and set aside. Drain off all but about 2 tbsp of the oil.

Return the wok to the heat with the chillies and Sichuan pepper and sizzle briefly until the chillies are darkening but not burned and the oil is wonderfully fragrant. Add the ginger, garlic and spring onions and stir-fry briefly until you can smell them. Then return the mushrooms and stir into the fragrant oil. Give the sauce a stir and add it to the wok, stirring swiftly as it thickens. Finally, stir in the peanuts and serve.

For most Chinese people, soup is an essential part of a meal. Sometimes it is served as an appetizer, but more often it is offered alongside other dishes, or towards the end of the meal.In restaurants, the soup may be served in individual bowls, while at home, a great bowlful of soup—the equivalent of a Western tureen—will be placed on the table with a serving spoon so everyone can help themselves.

While the soups served in Chinese restaurants abroad tend to be the dense, somewhat heavy soups that the Chinese call

geng

(a soup thick with finely cut ingredients), most Chinese meals include a very lightly seasoned broth (known as a

tang

) to refresh the palate after the other dishes. In a Sichuanese home, this might be as simple as a broth made by simmering pickled mustard greens in water, with a few bean thread noodles added at the end.

Traditionally, the soup might be the only liquid served with a meal, which is perhaps why Chinese people always talk of “drinking” soup rather than “eating” it. The way to consume a typical home-cooked soup is to ladle some into your empty rice bowl after you’ve eaten your fill of the other dishes. Then use your chopsticks to eat the solid pieces of food from the soup and drink the liquid from the lip of the bowl. Where the soup contains pieces of meat or poultry, they may be dipped into a little dish of soy or chilli bean sauce before eating.

Although Chinese soups are generally eaten as part of a Chinese meal, as described, many of them also work well as Western appetizers.

Because the soups that follow are intended to be shared, portion sizes are inexact, but as a general rule a soup of 6 cups (about 1½ liters) will serve up to six people.

SOUP OF SALTED DUCK EGGS, SLICED PORK AND MUSTARD GREENS

JIE CAI XIAN DAN ROU PIAN TANG

芥菜鹹蛋肉片湯

This refreshing, savory soup is an everyday Cantonese classic: a light broth dense with leafy greens and enlivened by scrumptious morsels of pork and salted egg. Many Chinese chefs in the West know how to make it, but it’s rarely listed on English language menus. Chicken can be substituted for the pork, while vegetarians will enjoy the soup with a vegetarian stock and no meat at all.

Don’t be alarmed by the instruction to “cut the yolks into small pieces”: the process of salting the duck eggs transforms the yolk into a golden, waxy sphere which can be cut with a knife, while the white remains runny.

5 oz (150g) pork tenderloin

2 salted duck eggs

11 oz (300g) preserved mustard greens

½ oz (20g) piece of ginger

6⅓ cups (1½ liters) chicken stock

3 tbsp cooking oil

Salt

For the marinade

½ tsp salt

½ tbsp Shaoxing wine