Evolution's Captain (20 page)

Read Evolution's Captain Online

Authors: Peter Nichols

Bynoe, the ship's surgeon, told him he was suffering from overwork, that he should ease up and he would recover. But FitzRoy would not believe him. He felt madness burrowing its way through him. He spoke of the suicide of his uncle who had slashed his own throat, and he grew convinced that a hereditary susceptibility to that same maggoty decay was now attacking his mind. Both he and Bynoe were right: overwork, strain, uncertainty, and disappointment had crushed his delicate mental foundation and sent him spinning into a void.

He finally did the unthinkable: he relieved himself of command, appointing First Lieutenant Wickham commander of the

Beagle

. FitzRoy's instructions from the Admiralty always allowed for such an occurrence and were eerily clear about what was then to happen:

In the event of any unfortunate accident happening to yourself, the officer on whom the command of the Beagle may in consequence devolve, is hereby required and directed to complete, as far as in him lies, that part of the survey on which the vessel may be then engaged, but not to proceed to a new step in the

voyage; as, for instance, if at that time carrying on the coast survey on the western side of South America, he is not to cross the Pacific, but to return to England by Rio de Janeiro and the Atlantic.

There would, in this case, be no continuing the voyage around the world.

Darwin wrote home of his profound disappointment, and his conflicted feelings about the voyage's growing length.

As soon as the captain invalided, I was at once determined to leave the

Beagle

; but it was quite absurd what a revolution in five minutes was effected in all my feelings. I have long been grieved and most sorry at the interminable length of the voyage (although I never would have quitted it). But the minute it was all over, I could not make up my mind to returnâI could not give up all the geological castles in the air which I had been buildingâ¦. One whole night I tried to think over the pleasure of seeing Shrewsbury again, but the barren plains of Peru gained the day.

It was Lieutenant Wickham, FitzRoy's loyal second-in-command, who brought his captain round. He pointed out that the Admiralty's instructions for the survey of the southwest coast of South America were to do not all of it but as much as was conveniently possible within a reasonable periodâand then to proceed across the Pacific. If he took command, Wickham said, nothing would induce him to spend more time in Tierra del Fuego. So what was to be gained by the captain's resignation? he asked FitzRoy. Wickham urged him to reconsider, to accept the sufficiency of what they had already done, to continue the mission by crossing the Pacific and returning to England at the conclusion of the circumnavigation all hoped to achieve. FitzRoy pondered this a short while and then agreed. He withdrew his resignation. Darwin wrote home with the good news.

To have endured Tierra del Fuego and not seen the Pacific would have been miserableâ¦. When we are once at sea, I am sure the captain will be all right again. He has already regained his cool inflexible manner, which he had quite lost.

FitzRoy spent another year surveying the west coast of South America, but he stayed north of Tierra del Fuego, ranging between the temperate Patagonian island of Chiloé and the tropical waters above Lima, Peru.

On September 7, 1835, almost four years after leaving England, the

Beagle

at last sailed away from the continental coast of America, out onto the vast and storied Pacific.

History had wobbled for a moment as FitzRoy's despair got the better of him; the

Beagle

had almost turned around and sailed for home. But then her captain recovered, and she pointed her bow northwest toward a small scattering of islands on the equator, and history shifted its weight onto the

Beagle

's unsuspecting natural philosopher.

E

arly voyagers called them the Enchanted Islands, but not

because of anything they offered a passing sailor. They were hard to find, elusive, chimerical. They lay in a belt of fitful winds and humid cloud known as the Doldrums. Strong ocean currents played around them. With skies too overcast for celestial navigation, their ships drifting in unknown directions and spinning on ocean gyres, early navigators felt as if their instruments and the sea itself around these islands were bewitched. FitzRoy's task was to fix their location exactly.

Darwin's was to discover the clues that would underwrite his enduring fame. He would do it quickly: his momentous visit to the Galapagos Islands lasted just thirty-four days, and it would be more than a year later until he had any idea what he had really found there.

After the lushness of the tropics and the epic grandeur of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, Darwin found the islands disappointing. They were hot and uncharming. “All the plants have a wretched, weedy appearance, and I did not see one beautiful flower.” The flowers he did find were “insignificant, ugly little flowers.” He took great pains to collect insects but, “excepting Tierra del Fuego, I never saw in this respect so poor a country.

Even in the upper and damp region I procured very few,” and those he found were “of very small size and dull colours.”

The tortoises were more fun.

The inhabitants believe that these animals are absolutely deaf; certainly they do not overhear a person walking close behind them. I was always amused when overtaking one of these great monsters, as it was quietly pacing along, to see how suddenly, the instant I passed, it would draw in its head and legs, and uttering a deep hiss fall to the ground with a heavy sound, as if struck dead. I frequently got on their backs, and then giving a few raps on the hinder part of their shells, they would rise up and walk away;âbut I found it very difficult to keep my balance.

He found the iguana lizards “most disgusting.”

He noticed what everyone notices, or used to, in the Galapagos Islands: “The birds are strangers to man and think him as innocent as their countrymen the huge tortoises. Little birds, within three or four feet, quietly hopped about the bushes and were not frightened by stones being thrown at them. Mr King killed one with his hat and I pushed off a branch with the end of my gun a large hawk.”

Most notably, Darwin observed and collected a number of birds with very different beaks. At the time, he believed these different beaks indicated different genera, or kinds, of birds: thrushes, finches, blackbirds.

It was not until much later, when his specimens had been examined by experts in England, that Darwin learned what was remarkable about his collections from the Galapagos Islands: the majority of all the animals and flowering plants were aboriginal. They were not found anywhere else.

While Darwin fossicked and collected, the

Beagle

sailed through the islands on its surveying mission.

One of the ship's anchorages was Post Office Bay on Floreana

Island. The name had sprung from a custom established by whaling ships, mostly those from Nantucket and New Bedford, that had been calling at the Galapagos Islands since the 1780s, almost fifty years before the

Beagle

's arrival. Not only did the islands lie across the migratory path of whales; they provided the whaleships with large numbers of tortoises, which lumbered around their decks until slaughtered for fresh meat. In this sheltered bay, a whale-oil barrel had been erected with a small roof over it to hold letters which could be deposited and collected by newly arrived and homebound vessels. On voyages often lasting three or four years, such a mail drop was a treasure trove for seamen anxious for news of their families.

“Since the island has been peopled the box (barrel) has been empty, for letters are now left at the settlement,” wrote FitzRoy. He was mistaken. The tradition held among the whalers for much of the nineteenth century and was continued by cruisers aboard sailing yachts well into the twentieth century. In December 1928, American William Albert Robinson, bound from New York around the world aboard the 32-foot ketch

Svaap

, posted a letter here. The barrel in which he left his letter was “a new one erected not long ago by the

St George

âa British scientific expedition. But a few feet back in the brush I found a very old weathered cask with the letters

U.S

.

MAIL

still faintly visible. It was the last remaining trace of what was probably the world's most romantic postal service.” Robinson's letter followed him shortly afterward, taken on to Tahiti by the

Illyria

, a brigantine on a scientific cruise of the South Seas.

In December 1933, Irving and Electa Johnson and their crew aboard the 92-foot schooner

Yankee

left a letter in “the barrel stuck on top of a poleâ¦and many months later found it had worked: a passing yacht had acted as mailman.”

John Caldwell, a newly discharged American GI, stopped here in his 29-foot boat

Pagan

in July 1946. Caldwell had left his Australian war bride Mary in Sydney almost a year earlier

and, with the immediate postwar scarcity of transportation, had been unable to get back to her since by plane or ship. In desperation, stranded in Panama, he bought

Pagan

, a rundown cutter, and headed across the Pacific without knowing how to sail or navigate. He did manage to reach Post Office Bay and left the bulky letter he'd been writing to Mary, wrapped with a five-dollar bill and a rubber band, in “the parched ornamental barrel” he found on the beach. His voyage had already been hellish, and Caldwell was very uncertain that he'd live to make it across the Pacific to his wife.

Five dollars from my small remaining funds was a lot; but I wanted Mary to get that letter, and if five dollars would insure itâand I felt it wouldâthen the money didn't matter. I stood by the traditional landmark for a moment wondering if the letter would ever reach Maryâ¦.

As I rowed out to

Pagan

I was oblivious to the dismal countenance of the surroundings or the growing cold. My mind was across the Pacific. It was also with the letter in the barrel. An unholy melancholy was on me. I was swept with the futile remorse of great desire, hindered by need of lengthy patience, and burdened by uncertainty.

Caldwell “posted” his letter on July 22 and sailed away the next day. Some vessel picked it up because ten weeks later, in early October, Mary received it in Sydney. It informed her that he hoped to arrive in

Pagan

around the end of September. In other words, he was then at least a week late. But

Pagan

didn't make it. Caldwell survived a hurricane, but shipwrecked on the reefs of the Fiji Islands. He lived, though, to crawl ashore across the rocks and eventually make his way by copra ship, motor bus, and army bomber to Sydney, where he was reunited with Mary on December 3, 1946. (John Caldwell wrote the full story of this adventure in his book

Desperate Voyage

.)

Â

Watered, wooded, and carrying “thirty large terrapin on board,”

the

Beagle

dropped the Galapagos Islands astern on October 20 and sailed southwest across the Pacific.

FitzRoy's instructions, beyond the South American survey, were to take only what time he needed to make celestial observations that would establish a chain of consecutive longitude distances around the globe, back to the vessel's starting point at Plymouthâback to that rock in Plymouth breakwater which had been the starting point for all his longitude observations. The rest of the world, after South America, was covered with the thoroughness of a five-day, ten-country bus trip across Europe. The ship spent only ten days in both Tahiti and New Zealand. The speed of the return voyage, the light duty now that surveying was largely behind them, gave the men aboard the relative leisure to view the world as regular tourists.

FitzRoy was astonished at the size of Sydney. “I saw a well-built city covering the country near the port.” But he didn't think it would last, and, like many since, he had a low opinion of Australian culture.

It is difficult to believe that Sydney will continue to flourish in proportion to its rise. It has sprung into existence too suddenly. Convicts have forced its growth, even as a hot-bed forces plants, and premature decay may be expected from such early maturityâ¦.

There must be great difficulty in bringing up a family well in that country, in consequence of the demoralizing influence of convict servants, to which almost all children must be more or less exposed. Besides, literature is at a low ebb; most people are anxious about active farming, or commercial pursuits, which leave little leisure for reflection, or for reading more than those fritterers of the mind, daily newspapers and ephemeral trash.

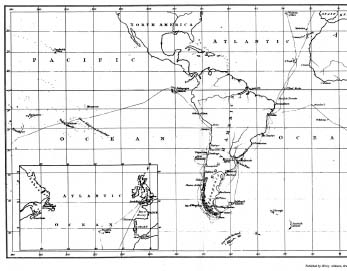

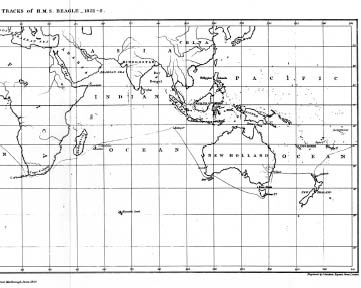

Map from FitzRoy's

Narrative

showing the

Beagle

's track around the world. (Narrative of HMS

Adventure

and

Beagle, by Robert FitzRoy

)

The

Beagle

remained in Sydney only two weeks. As the ship moved across the globe toward England, its crew grew hungrier for home. None more so than her captain, on whom the weight of the voyage had taken a visible toll. Phillip Parker King, FitzRoy's commander aboard HMS

Adventure

on the

Beagle

's first voyage, had moved to Sydney, and FitzRoy called upon him there. King was appalled at the change in his former youthful commander, now still only thirty years old.

Sydney, 2 February 1836

My dear Beaufort,

You will have heard from FitzRoy who has been here a fortnight and sailed on the 30th for Van Diemens Land on his return. I regret to say he has suffered very much and is yet suffering much from ill healthâhe has had a very severe shake to his constitution which a little

rest

in England will I hope restore for he is an excellent fellow and will I am satisfied yet be a shining ornament to our serviceâ¦.

Very truly yours

Phillip P. King

And Darwin, in a letter home at the same time, echoed King's concern, and added one more thought.

From Sydney we go to Hobart Town, from thence to King George Sound and then adios to Australia. From Hobart Town being super-added to the list of places I think we shall not reach England before September: But thank God the captain is as home sick as I am, and I trust he will rather grow worse than betterâ¦. I have been for the last twelve months on very cordial terms with him. He is an extraordinary but noble character, unfortunately, however, affected with strong peculiarities of temper. Of this, no man is more aware than himself, as he shows by his attempts to conquer them.

I often doubt what will be his end; under many circumstances I am sure it would be a brilliant one, under others I fear a very unhappy one.