Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (52 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

11.

Churg-Strauss vasculitis:

50% of patients will have a positive perinuclear (p) ANCA test. The other important diagnostic tool is the tissue biopsy, which will reveal intense eosinophilia. Sural nerve biopsy will sometimes be required in the setting of neuropathy and this will show vasculitis.

12.

Microscopic polyarteritis:

this is characterised by a positive p-ANCA result. This antibody is directed against myeloperoxidase. Renal biopsy is usually necessary to establish the diagnosis.

13.

p-ANCA is rare in other inflammatory diseases, but common in patients with vasculitis (c-ANCA is specific for Wegener’s granulomatosis). ANCA titres do not correspond with the clinical severity of the patient’s illness and they may be only markers of disease. Remember that p-ANCA tests may be positive (but myeloperoxidase – MPO negative) in other conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, as well as in health (5%).

Treatment

Systemic vasculitis will generally require aggressive immunosuppressive medication. Failure to suppress the vasculitis aggressively can result in permanent injury, progressive deterioration and death.

1.

Wegener’s granulomatosis (deadly if untreated):

high-dose corticosteroids and daily oral cyclophosphamide should be instituted. Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole is adjunctive therapy. Biological agents are being investigated for treatment of Wegener’s. Rituximab shows the most promise, but should not be used at this stage unless other agents have failed.

2.

Giant cell arteritis:

high-dose oral corticosteroids are required, typically for 1 to 2 years.

3.

Polyarteritis nodosa:

the untreated 5-year survival rate is less than 20%. A combination of high-dose prednisone and cyclophosphamide will usually be very effective (90% long-term remission). Treatment may often be discontinued after remission is obtained and the long-term prognosis is very good. Interferon alpha, or the antiviral drug vidarabine, may help to induce remission if there is associated hepatitis B infection.

4.

Churg-Strauss vasculitis:

the eosinophilic vasculitis of the Churg-Strauss syndrome is generally very steroid responsive, but occasionally other cytotoxic agents need to be used. Steroids alone have been shown to increase the 5-year survival rate from 25% to 50%.

5.

Microscopic polyarteritis:

corticosteroids combined with immunosuppressive agents are usually required, with renal support in patients who develop renal failure.

6.

The duration of treatment for all of these vasculitic illnesses needs to be individualised. Patients with giant cell arteritis can come off treatment after about two years, but some have disease for several years. Most of the other diseases will require maintenance therapy.

7.

Patients often suffer the effects of long-term steroid therapy and immunosuppression, such as osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes and accelerated vascular disease. Prevention should be aggressively pursued. Infection (e.g.

Pneumocystis

pneumonia) is common in this group and can be serious or fatal.

8.

Patients on cyclophosphamide need careful monitoring of their blood count and careful counselling to ensure adequate fluid intake and avoid haemorrhagic cystitis. They also deserve an annual urinalysis for haematuria once therapy is ceased; haematuria may indicate the development of bladder cancer.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome is a disease that not infrequently requires patients to be admitted to hospital for its various complications. It therefore may crop up as a long case in the examination. The disease can be either primary or secondary. The secondary form is usually a complication of other autoimmune conditions, the most common of which is SLE. The main antibody in this disease is directed against the phospholipid-beta2-glycoprotein 1 complex, on which it exerts a procoagulant effect. It has also been described in HIV infection.

The history

Patients with antiphospholipid syndrome commonly suffer thrombosis (

Table 9.14

).

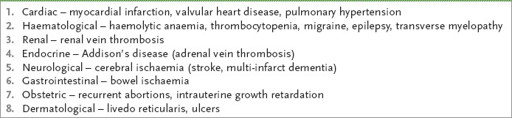

Table 9.14

Clinical manifestations of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

1.

Ask about venous thromboses. The most common site is the deep lower limb or pelvic veins, but the axillary veins can be involved.

2.

Ask about arterial thromboses. Stroke and myocardial infarction are the most common arterial complications.

3.

Enquire about a history of recurrent first-trimester and later abortion. Antiphospholipid syndrome is far more common in females and otherwise unexplained first-trimester abortions are characteristic of this disease. Other obstetric complications include intrauterine growth retardation and an increased tendency for hypertension in pregnancy.

4.

Ask about bleeding problems associated with thrombocytopenia, skin changes (especially livedo reticularis), central nervous system complications such as migraine and chorea, and eclampsia or pre-eclampsia with the HELLP syndrome:

H

aemolysis,

E

levated

L

iver enzymes,

L

ow

P

latelets

5.

Ask about features of the underlying disorder, such as SLE, which suggest the patient has a secondary form of antiphospholipid syndrome.

The examination

Unless the patient has an active thrombosis there are unlikely to be any abnormal physical signs. Look especially for:

1.

signs of any associated autoimmune diseases, particularly skin rashes and joint abnormalities in SLE, and dry eyes and mouth in Sjögren’s syndrome

2.

livedo reticularis rash on the lower limbs

3.

heart murmurs from sterile valve vegetations.

Investigations (see also

p. 166

)

1.

The detection of IgG anticardiolipin antibodies is diagnostic for the antiphospholipid syndrome if the antibodies are in high titre and found in the correct clinical context. IgM anticardiolipin antibodies may be detected, although these are less specific.

2.

The lupus inhibitor is a related antibody (both are antibodies to phospholipid) that confers an even greater risk of thrombosis and pregnancy complications. The lupus inhibitor is also associated with a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) not corrected in a mixing study.

3.

Antibodies to beta2-glycoprotein-1 (β2-GP-1) in high titre may be present in the appropriate clinical setting.

4.

In any patient with antiphospholipid syndrome it is worth checking the ANA and other autoimmune serology as indicated. The platelet count should also be measured. The venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test may be falsely positive.

Treatment

1.

Any patient with thrombotic complications of the antiphospholipid syndrome should be considered for treatment with anticoagulants for life (consider whether the benefits exceed the risks for individual patients).

2.

The patient with anticardiolipin antibodies, but no clinical abnormalities, presents a difficult clinical situation. There are no data to support routine anticoagulation in this situation, but clearly there is a risk of arterial thrombosis.

3.

The patient who has had obstetric problems in the past but no history of thrombosis also presents a dilemma for clinicians. The literature supports the use of anticoagulation therapy only in those with anticardiolipin antibodies or lupus inhibitor in whom a thrombotic complication has previously occurred.

4.

Women who have suffered recurrent abortion will require treatment during pregnancy. Low-molecular-weight heparin would normally be used throughout the pregnancy, with the addition of low-dose aspirin. There is no good evidence that corticosteroids improve survival of the fetus.

Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

This is a progressive disease of multiple organs. Although a rare disease, it crops up commonly in examinations. It is more common in women (5:1). The 5-year survival at diagnosis is only 70%. Asian patients have a higher incidence of diffuse disease and of interstitial lung disease. There is a slightly increased risk of disease for people who have a first degree relative affected.

The history

1.

Ask about symptoms:

a.

dermatological symptoms – Raynaud’s phenomenon (commonly the first symptom), tight skin, disability from sclerodactyly

b.

arthritis – arthropathy in a rheumatoid distribution, carpal tunnel symptoms

c.

gastrointestinal symptoms – dysphagia, heartburn (oesophagitis), diarrhoea (malabsorption)

d.

renal tract symptoms – hypertension, chronic kidney disease

e.

respiratory symptoms – symptoms of interstitial lung disease, pleurisy, known diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension

f.

cardiac symptoms – symptoms of pericarditis, palpitations (arrhythmias), symptoms of cardiac failure (dilated cardiomyopathy)

g.

other symptoms – erectile dysfunction, hypothyroidism, history of non-melanoma skin cancer.

2.

Consider the differential diagnosis (

Table 9.15

). Graft versus host disease can mimic scleroderma. Also ask about a history of exposure to polyvinyl chloride (PVC), l-tryptophan (eosinophilic myalgia syndrome) and drugs (e.g. bleomycin, pentazocine). Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis can occur in dialysis patients exposed to gadolinium during an MRI. Also ask about drugs likely to aggravate Raynaud’s phenomenon (e.g. beta-blockers); a possible association with silicone breast implants seems to have been negated. Don’t miss diabetic-induced skin thickening.

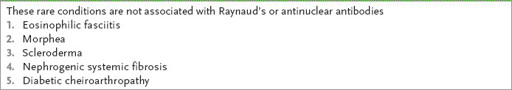

Table 9.15

Differential diagnosis of scleroderma

3.

Ask about treatment received (e.g. d-penicillamine) and side-effects thereof (see

Table 9.18

).

Table 9.18

Side-effects of d-penicillamine

| SEVERE | MORE MINOR |

| Glomerulonephritis and nephrotic syndrome | Alteration of taste |

| Myasthenia gravis | Skin rashes |

| Thrombocytopenia | Fever |

| Leucopenia | Nausea |

| Aplastic anaemia | Anorexia |

4.

Enquire about degree of disability – function at home, ability to work, financial security.

Scleroderma may be classified as limited or diffuse. Limited disease means involvement of the skin up to the elbows (and may include the face) without chest, abdominal or internal organ involvement, except for the oesophagus. These patients are usually anticentromere positive.

In CREST (typically a more limited form of scleroderma, usually with oesophageal involvement, which causes dysphagia), sclerodactyly is usually limited to the distal extremities and/or face. The signs are:

•

C

alcinosis (calcific deposits in subcutaneous tissue at the ends of the fingers) (see

Fig 9.10

)