Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (55 page)

11.

Steroid-induced osteoporosis

. This is very important because, if prednisone is considered likely to be needed for a number of months or longer, then measures to prevent bone loss are important from the time steroids are begun, particularly

in postmenopausal women or when high doses are needed. Co-administration of bisphosphonates is of value here. Calcium and 25-OH vitamin D in combination have also been shown to be effective. These are the only drugs that have been shown to reduce fracture risk for patients on steroids. Other general measures, such as cessation of smoking and a regular exercise regimen, are probably important and should be recommended to the patient.

12.

Surgical treatment of fractures

. This is often required. Frail elderly patients with other medical problems require careful assessment of anaesthetic risk.

Vertebral fractures may cause severe pain that requires potent analgesics. Bed rest should be as brief as possible. Injection of bone cement into the vertebral body (vertebroplasty) is a new treatment that may relieve pain and possibly has other benefits.

Hypercalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia is a common medical problem and therefore can appear in a long case. It is most likely to be a diagnostic problem. Most patients (90%) have hyperparathyroidism or malignancy (

Table 10.6

). The asymptomatic patient usually has hyperparathyroidism. A malignant condition that is advanced enough to cause hypercalcaemia is likely to have caused other symptoms.

Table 10.6

Causes of hypercalcaemia

CKD = chronic kidney disease.

The history

1.

If the patient tells you that he or she has high calcium levels, enquire about the non-specific symptomatic manifestations. These include tiredness, weakness and episodes of confusion. Enquire about anorexia and constipation, as well as nausea and vomiting; acute abdominal pain from acute pancreatitis may have occurred. Enquire about polyuria and polydipsia. Ask about a history of hypertension or a slow heart rate.

2.

Enquire about a history of peptic ulcer or renal colic (‘stones, moans, bones and abdominal groans’ from primary hyperparathyroidism). Ask about joint pain from pseudogout (chondrocalcinosis in primary hyperparathyroidism). Enquire about a past history of hypertension (hyperparathyroidism).

3.

Ask the patient whether he or she was known to have a neck mass in the past or has had an operation to remove the parathyroid gland. In most cases a single adenomatous gland is found but they can be multiple. Surgical parathyroidectomy is the definitive treatment for primary hyperparathyroidism. Most neck masses will be coincidental thyroid nodules rather than a benign or malignant parathyroid tumour.

4.

Ask whether the patient has had an eye examination and whether calcium was seen (band keratopathy). Also ask whether X-rays of the bones have been taken. In hyperparathyroidism, X-rays of the hand may show subperiosteal reabsorption with a moth-eaten appearance on the radial sides of the phalanges and in the distal phalangeal tufts (osteitis fibrosa cystica), as well as in the distal clavicles.

5.

Determine whether there is any past history of malignant disease, including diseases that metastasise to bone (e.g. carcinoma or myeloma) or haematological disease such as lymphoma (ectopic vitamin D production).

6.

Ask about drugs, including thiazide diuretics, lithium and ingestion of calcium or vitamin D.

7.

Enquire about known chronic kidney disease, a cause of secondary hyperparathyroidism because of resistance to parathyroid hormone and growth of the size of the glands. These enlarged glands then produce partly non-suppressible parathyroid hormone and hypercalcaemia.

8.

Ask about symptoms of thyrotoxicosis or phaeochromocytoma. Ask about recent immobilisation.

9.

Check whether there is a family history of high serum calcium levels, such as familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (autosomal dominant). Classically a patient with this condition has had hypercalcaemia since a relatively young age, with only a slight elevation in the serum parathyroid hormone level at most, and with a personal or family history of unsuccessful neck exploration; it does not require any therapy. A family history of hypercalcaemia may also occur with the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes, MEN1 and MEN2A. These are both autosomal dominant conditions. These patients may have symptoms related to the other features of their MEN syndrome (e.g. peptic ulceration from the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome owing to excess gastrin secretion).

10.

Many patients are asymptomatic and had hypercalcaemia detected on a routine set of biochemical tests. Hyperparathyroidism has been recognised much more commonly since automated biochemical analyses have become routine.

The examination

1.

Look for any evidence of a neck scar from parathyroid surgery, as well as forearm scars from re-implantation of the parathyroid gland from the neck.

2.

Evaluate the patient for evidence of malignancy, including lymphadenopathy or organomegaly.

3.

Look for evidence of renal failure.

4.

Carefully evaluate the respiratory system for any evidence of sarcoidosis, as well as tuberculosis or histoplasmosis.

5.

Take the pulse for bradycardia, a result of a high serum calcium level. Measure the blood pressure for evidence of phaeochromocytoma.

6.

Examine for signs of thyrotoxicosis.

7.

Look for pigmentation from Addison’s disease.

8.

Examine for proximal weakness and signs of pseudogout in the joints.

9.

Examine the cornea for band keratopathy (calcification horizontally across the centre of the cornea).

Investigations

1.

Look at the total serum calcium level. Remember that apparently high calcium levels can be the result of haemoconcentration while the blood is being collected. Correct for hypoalbuminaemia: add 0.02 mmol/L to the serum calcium concentration for every 1 g/L by which the serum albumin level is less than 40 g/L. The calcium level at which symptoms occur varies, but most patients have symptoms when the corrected calcium level reaches 3 mmol/L. Higher levels are associated with tissue calcification and the risk of renal failure, especially if the phosphate level is normal or increased by renal impairment. Once the calcium level approaches 4 mmol/L, unconsciousness and cardiac arrest can occur.

2.

Measure the parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. If elevated, primary hyperparathyroidism is the most likely diagnosis (the PTH can be inappropriately in the high normal range in 10%; the phosphorous should be low). If the patient is taking lithium or thiazide, the test should be repeated after discontinuing drug treatment, because these drugs may influence both calcium and parathyroid hormone secretion.

3.

In a young otherwise asymptomatic person with a marginal elevation of parathyroid hormone, a 24-hour urine calcium examination should be asked for to exclude familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH). Alternatively, collect a fasting morning spot urine and measure the urine calcium/creatinine clearance ratio (<0.01 in FHH). This autosomal dominant condition is caused by faulty calcium sensing by the parathyroid glands and renal tubules.

4.

If there is a low or undetectable parathyroid hormone level, consider the possibility of granulomatous disease, including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, berylliosis, leprosy and lymphoma. An increased level of 25-OH vitamin D supports this possibility.

5.

Ask to review the chest X-ray. Investigations to look for malignancy if suspected may then be required (e.g. protein electrophoresis, CT scan etc.).

Treatment

There is evidence that asymptomatic patients with hyperparathyroidism who are not treated have increased bone loss compared with controls. Significant increases in fracture risk (especially of the wrist and spine) have been demonstrated.

1.

If the diagnosis is hyperparathyroidism and the patient is symptomatic, has renal stones or has a reduced bone density, surgical parathyroidectomy is usually indicated. If the patient is asymptomatic, then treatment is more controversial, but younger patients (<50 years) with higher serum or 24-hour urine calcium levels will usually be offered surgery. Preoperative localisation is not required for the skilled surgeon, but if there is a need for a repeat procedure this can be evaluated using ultrasonography, CT or technetium-99m sestamibi scanning.

2.

Note whether there has been hypocalcaemia after surgery. If there is no residual parathyroid tissue left, lifelong vitamin D therapy is necessary or, alternatively, autotransplantation of parathyroid tissue into the forearm may be offered.

3.

Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with vitamin D deficiency. Treatment is controversial if the patient is unfit for surgery, but cautious calcium and vitamin D replacement is probably safe and desirable.

4.

In malignant hypercalcaemia the underlying tumour should be treated. Steroids are often effective in lowering the serum calcium level. With granulomatous disease, steroids are also effective in lowering the calcium level (but avoid if infection is the cause); chloroquine may be useful in patients who cannot tolerate steroids. Lithium treatment may need to be stopped. Hypercalcaemia does not necessarily mean lithium toxicity.

5.

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia rarely causes symptoms and should not be treated with parathyroidectomy. Consider screening all first-degree relatives.

6.

In an emergency, rehydration with intravenous saline and frusemide is indicated for hypercalcaemia. Parenteral calcitonin lowers calcium levels only transiently. The use of intravenous bisphosphonates is very effective.

Paget’s disease of the bone (osteitis deformans)

This is usually a disease of the elderly, but it may occur in younger patients. In populations from western or southern Europe up to 10% of people over the age of 85 are affected. The condition is characterised by excessive resorption of bone and increased formation

of new bone in an irregular ‘mosaic’ pattern. Bone turnover may be increased 20 times early on in the course of the disease. The aetiology is unknown but may be caused by a persistent paramyxovirus infection of osteoclasts. There are reports of familial occurrence (15% have a family history) and of autosomal dominant inheritance. The condition is rare in Asian populations. It presents as a management problem.

The history

1.

Ask about symptoms that led to the diagnosis:

a.

isolated elevation of alkaline phosphatase on routine blood testing

b.

an incidental finding on an X-ray

c.

bone pain

d.

secondary osteoarthritis

e.

change in height or hat size

f.

progressive bone deformity or pathological fracture; gait abnormalities associated with change in length of a long bone

g.

neurological symptoms – hearing loss, neurological gait disturbance (suggestive of basilar invagination with long tract signs, or cerebellar involvement or spinal cord compression), cranial nerve symptoms, headache

h.

symptoms of congestive cardiac failure

i.

symptoms of renal colic (as there is an increased incidence of calcium nephrolithiasis in this disease, especially during the resorptive phase)

j.

gout, secondary to increased bone turnover

k.

sarcoma of bone (very rare – less than 1% of cases, occasionally multicentric)

l.

symptoms of hypercalcaemia – thirst, polyuria, nausea, coma (a rare occurrence even in immobilised patients, or alternatively caused by coexisting primary hyperparathyroidism, which is common)

m.

pathological fractures, especially of the convex side of weight-bearing bones; can be multiple.

2.

Enquire about articular pain, which may be caused by secondary osteoarthritis in joints adjacent to sites of Pagetic involvement, and true bone pain. Secondary osteoarthritis is characterised by pain and stiffness, which improves with joint movement; alternatively it may initially be exacerbated by weight-bearing and relieved by rest. True bone pain is more often constant or gnawing and is worse at night. A sudden exacerbation of bone pain may indicate a pathological fracture or the development of an osteosarcoma.

3.

Ask about treatment, its effectiveness and side-effects.

4.

Enquire about disability at home and work. Remember, though, that most patients are asymptomatic.

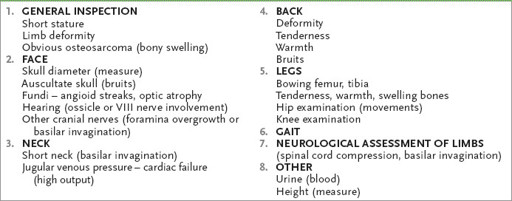

The examination (see

Table 10.7

)

Table 10.7

Paget’s disease