Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (59 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

iii.

weight gain (owing to increase in appetite and mild hypoglycaemia)

iv.

bone marrow depression

v.

cholestatic jaundice

vi.

skin rash

vii.

alcohol intolerance, causing flushing

viii.

water retention and hyponatraemia (syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone).

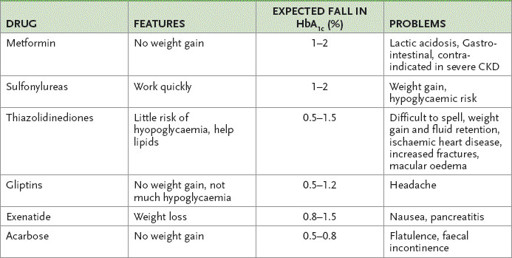

The effectiveness of the sulfonylureas is variable and rates of secondary failure vary between agents. Primary failure occurs in 40% of cases and secondary failure in 3–30%; only 20–30% of patients continue with satisfactory control. Substitution of one drug for another may be worth trying (

Table 10.15

).

Table 10.15

Oral hypoglycaemic agents

c.

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are a newer class of oral hypoglycaemic drugs (

Table 10.15

). They reduce insulin resistance, blood sugar levels and triglycerides. Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are available in Australia: their use is restricted to patients whose HbA

1c

is over 7% during the preceding 3 months and who are on maximum tolerated doses of metformin and a sulfonylurea. Patients on insulin must also be on metformin and have a raised HbA

1c

. Liver function tests must be performed every 2 months for the first year and the drug stopped if the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level rises above 2.5 times normal. The drugs are associated with small rises in HDL and LDL cholesterol and with peripheral oedema. Some are associated with an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease. They are contraindicated for patients with class III or IV heart failure.

d.

Acarbose inhibits intestinal alpha-glucosidase, slowing polysaccharide degradation and absorption. It is a useful agent taken before meals with other treatment. Side-effects include flatulence, diarrhoea and abdominal pain, but there is no major toxicity.

e.

The gliptins (DPP-IV inhibitors) sitaglitin, vidagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin increase the levels of incretin peptides (e.g. glucagon-like peptide) by inhibiting their degrading enzyme. Insulin release is increased and glucagon suppressed. They can only be used in combination with metformin or a sulfonylurea except for linagliptin which can be used with both. They are weight neutral and can be used in old patients but chronic kidney disease is a relative contraindication.

f.

GLP-1 analogues. The only approved drug currently is exenatide. This glucagon analogue is resistant to DPP IV degradation. It has to be given by injection twice a day. It can be especially useful for overweight patients.

INSULIN THERAPY

1.

Insulin requirements initially are generally between 0.4 and 1.0 U/kg/day. An anorectic agent should be considered when requirements exceed 1.5 U/kg/ day. Insulin therapy is often begun on an outpatient basis and under these circumstances small doses (e.g. 0.25 U/kg/day), sufficient to prevent ketosis, are used with a view to avoiding hypoglycaemia.

Modern insulins are either recombinant human insulin or analogue insulin (see

Table 10.16

). Analogue insulins have been genetically altered to maintain their monomeric form when injected subcutaneously. This better mimics physiological insulin release.

Table 10.16

Available insulins

| NAME | TYPE |

| HUMAN INSULINS | |

| Short-acting | |

| Actrapid | Neutral |

| Humilin R | Neutral |

| Short-acting | |

| Humulin NPH | Protamine suspension |

| Protaphane | Protamine suspension |

| Biphasic mixtures | |

| Humulin 30/70 | Protamine suspension +neutral |

| Mixtard 30/70 | Protamine suspension +neutral |

| Mixtard 50/50 | Protamine suspension +neutral |

| INSULIN ANALOGUES | |

| Rapid-acting | |

| Humalog | Lispro |

| Aprida | Clulisine |

| NovoRapid | Aspart |

| Biphasic analogue insulins | |

| Novomix 30 | Aspart +aspart protamine |

| Humalog mix 25 | Lispro + lispro suspension |

| Humalog mix 50 | Lispro +lispro suspension |

| Long-acting insulins | |

| Lantus | Clargine |

| Levemer | Detemir |

a.

Possible insulin regimens include: the basic bolus regimens, using a short-acting insulin at mealtimes, with an intermediate- or long-acting insulin at suppertime; twice-daily double mix, using a combination of short- and intermediate-acting insulin (premixed ratios – short:intermediate are commercially available (

Table 10.16

), or the patient may mix insulins in a syringe); and in patients with type 2 diabetes, a combination of oral hypoglycaemic agents at mealtimes with an intermediate- or long-acting insulin at supper is an option.

b.

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion is a treatment option, but infusion devices remain beyond the means of most patients with diabetes and may be associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality related to hypoglycaemia. The administration of intraperitoneal insulin via the dialysate can be useful in the management of patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), and continuous intraperitoneal infusion has been attempted in some centres.

c.

Human insulin has replaced the highly purified (monocomponent) insulins. Many patients reported altered symptoms of hypoglycaemia and a more rapid onset of symptoms after changing to human insulin. Aim for euglycaemia: ideally the glucose level should be between 3.5 and 7.0 mmol/L throughout the day and night.

2.

Insulin resistance is defined as a requirement of more than 200 units per day. Causes of insulin resistance are:

a.

obesity (decreased receptor number)

b.

insulin antibodies (uncommon, and an indication for a more purified insulin)

c.

circulating antagonist hormones – growth hormone (e.g. in puberty), cortisol, thyroxine, glucagon

d.

association with acanthosis nigricans (e.g. receptor abnormalities, lipodystrophies). Remember, injecting into a lipoatrophied site may cause poor control because of unpredictable absorption.

3.

Insulin allergy has been uncommon since the widespread introduction of human insulins, but they can cause immediate local reactions (e.g. pruritus, local pain) or delayed reactions (e.g. swelling). Urticaria and anaphylaxis can also occur. Treatment in mild cases is with antihistamines and local steroids, but in severe cases desensitisation is important. Insulin allergy is more common in patients who stop and start insulin therapy.

4.

Fasting hyperglycaemia is a major management problem. The ‘Somogyi effect’ refers to rebound morning hyperglycaemia following nocturnal hypoglycaemia, which is thought to be caused by the release of counter-regulatory hormones. This is now, however, a matter of considerable debate. The treatment is to reduce the evening insulin dose. The ‘dawn’ phenomenon is early morning hyperglycaemia in the

absence

of nocturnal hypoglycaemia; the treatment is to increase the insulin coverage without inducing hypoglycaemia.

5.

Causes of hypoglycaemia in a previously stable diabetic on insulin therapy are:

a.

decreased food intake, increased exercise or weight loss

b.

injection errors

c.

diabetic renal disease

d.

rare causes – high level of insulin antibodies, malabsorption, hypothyroidism, autoimmune adrenal insufficiency, panhypopituitarism or an insulinoma.

6.

Haemoglobin A

1c

gives an indication of control over the preceding three months: aim for a level of 53 mmol/mol (7%) or less, although the numbers may be distorted by one or two high blood sugar levels. Spurious readings may occur in kidney failure, iron deficiency, haemoglobinopathies and pregnancy.

DIABETES EDUCATION

Because diabetes is a lifelong disease, detailed education by the team looking after the patient is important. Regular follow-up is essential.

1.

Blood glucose monitoring with a glucose meter is essential for all patients who can manage it – initially, testing several times a day before and 2 hours after meals, and before bed, may be necessary; later, in stable diabetes, twice-daily may be enough.

2.

Exercise promotes glucose utilisation; in the well-controlled diabetic it is important to reduce the dose of regular insulin before exercise or supplement with glucose. (

Note:

Exercise in the poorly controlled diabetic may precipitate ketoacidosis because of increased release of counter-regulatory hormones.)

Management of chronic complications

Complications are probably a result of damage caused by glycosylated proteins. Convincing evidence that tight control prevents or reverses complications is now available. Following the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial published in 1994 and the more recent United Kingdom Prognosis in Diabetes Study (UKPDS), clinicians now agree that rigorous control of blood sugar levels and aggressive control of blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors is essential. These measures are probably more effective in the early stages of the disease.

1.

The blood pressure can be managed with any antihypertensive but the use of an ACE inhibitor or AR blocker (but not both) is strongly indicated when proteinuria has been detected, and is often used routinely. The goal blood pressure about 130/80 mmHg.

2.

Lipid control with the statins is being assessed in a number of trials. The high cardiovascular risk of these patients suggests that aggressive lipid-lowering with one of these drugs will be of value. Remember to control other risk factors, such as smoking (for retinopathy and vascular disease) and alcohol intake (for neuropathy and hypertriglyceridaemia). Aspirin prophylaxis is controversial, but for primary prophylaxis may be considered in older patients with one other risk factor (e.g. hypertension).

3.

Ideally, all patients should be assessed every 2 years by an ophthalmologist. Less sophisticated fundoscopy may miss early diabetic retinopathy (see

Table 16.43

). Retinal cameras can now be used at the clinic to take clear retinal photographs, which can be repeated often and ‘read’ by an ophthalmologist. Retinopathy almost always precedes diabetic nephropathy.

4.

Diabetic nephropathy is a common cause of chronic kidney failure and results from arteriolar disease or glomerulosclerosis (classic Kimmelstiel-Wilson lesion or, more commonly, diffuse intercapillary glomerulosclerosis). The evolution of diabetic nephropathy has been well studied and can be divided into the following stages:

a.

glomerular hyperfiltration

b.

microalbuminuria

c.

dipstick proteinuria

d.

proteinuria in the nephrotic range

e.

end-stage kidney disease.

5.

Microalbuminuria is defined as a urinary albumin excretion of 20 to 200 μg/ minute (measured using sensitive immunoassays) on more than two occasions in the absence of urinary tract infection and intercurrent illness. The albumin-to-creatinine ratio may be a more sensitive way of assessing the presence of significant proteinuria. Regular screening for microalbuminuria is now considered an important component of good diabetes management. The microalbuminuria stage is probably reversible with a combination of ACE inhibitor therapy, strict metabolic control and possibly dietary protein restriction.