Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (28 page)

Read Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs Online

Authors: Robert Kanigel

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Women, #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Public Policy, #City Planning & Urban Development

There was real energy to her talk, and love—love for the city. Lewis Mumford,

The

New Yorker

’s haughty architecture critic, was there to appreciate it. Her talk, he wrote her in a letter on May 3, “gave me

the deepest satisfaction.” It asserted ideas few planners “even dimly understand.” Her analysis of the ways cities worked “is sociologically of the first order.” Her takedown “of the vast bungle called Lincoln Center is devastatingly just.”

Lewis Mumford was a fan!

“None of the millions being squandered by the Ford Foundation for ‘urban research’ will produce anything that has a minute fraction of your insight and common sense.” He offered a few practical suggestions for where she might publish her writing, but for Jane this was probably the least useful part of his letter. “Keep hammering,” he told her. “Your worst opponents are the old fogies who imagine that Le Corbusier is the last word in urbanism.”

As we’ve seen, Jane rarely suffered any great want of confidence. But coming off the

Fortune

article and the letter from Mumford, which she probably received around May 5, she could hardly have felt on professionally firmer ground, when, on May 9, she met with Chadbourne Gilpatric.

Gilpatric had just returned from Philadelphia, where, as part of his efforts to bring urban design under the scrutiny and guidance of the Rockefeller Foundation, he’d visited the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Urban Research. He came back with a raft of interview notes, suggestions, books to read, and ideas about playgrounds, parks, gardens,

and cities, page after page of them. Now, two days later, he was meeting with Jane, Doug Haskell’s “person worth talking to.”

So the two of them talked. They talked about the Charles Center project in Baltimore and why she thought it better than most other redevelopment projects. She approved of Ian McHarg’s ideas for a series of books on civic design. She put in a good word for Ian Nairn, whom

Fortune

had brought to the United States for two weeks, urged that the Rockefeller give opportunities to first-rate architectural critics like Grady Clay, down in Louisville, whose work she much admired, or Nathan Glazer, who’d just written a perceptive piece for

Forum

on “The Great City and the City Planners.”

Then, finally, the conversation swung around to what

she

wanted to do. “

Mrs. Jacobs herself,” Gilpatric recorded, wanted to take three months to pursue something like the city streets project she’d discussed with

Forum

, which might run parts of it but probably couldn’t give her unbroken time to research and write it. So, “Mrs. J wonders” whether the Rockefeller would consider a grant, administered by the New School, to let her, and a researcher with whom she’d worked on the

Fortune

article, take leave to work on it.

Gilpatric told her that “this might well be a project of interest to the RF.”

A month later, the two of them met again. Now Jane was talking about eight or nine months, not three, and a book rather than a series of articles. “In this conversation as before,” Gilpatric wrote, “Mrs. J

fairly bubbled with interesting ideas about how to interpret human needs in modern city life.” They agreed that Jane would write him soon, laying out what she hoped to do in the book. For now, though, it came down to “ ‘what is the city’ or ‘what should the city be for people’ ”; the first, of course, was the distinctly immodest subject she’d suggested to Haskell two months earlier. Jane thought $10,000—worth perhaps $80,000 or $90,000 today—would let her do it.

Ten days later, Gilpatric had her proposal in hand. Jane would look into “five factors of the city”: streets, parks, scale, mixtures of people, and urban focal centers important out of all proportion to their size, like public squares. She would emphasize New York, especially East Harlem and Greenwich Village. She would aim for the “general interested citizen,” not the specialist. She appreciated that nine months was a tight deadline, but felt she did her best work under pressure.

“I’m afraid this

sounds very abstract,” Jane apologized at one point.

She was right; it did. Maybe she had come back with her proposal too soon, hadn’t thought it through enough. In any case, when she talked with Gilpatric on the phone two weeks later, he told her the Rockefeller was, yes, interested, but that “

questions about the scope and content of her work remained.” She, in turn, admitted dissatisfaction with what she’d submitted earlier. As Gilpatric set it down, she promised to “soon send in a clearer statement of the ‘nub’ of her study.”

A few days later, he had it. And this time there was fire to it, and an ambition she made no effort to tamp down.

Two mental images, she began, dominated people’s views of the city:

One is the image of the city in trouble, an inhuman mass of masonry, a chaos of happenstance growth, a place starved of the simple decencies and amenities of life, beset with so many accumulated problems it makes your head swim. The other powerful image is that of the rebuilt city, the antithesis of all that the unplanned city represents, a carefully planned panorama of projects and green spaces, a place where functions are sorted out instead of jumbled together, a place of light, air, sunshine, dignity and order for all.

You can guess where this was going: “Both of these conceptions are disastrously superficial.”

Here, she wrote, was the sort of sloppy thinking that led you into crude abstraction, that overlooked how a city really worked, and from which emerged “hindrances and blocks to intelligent observation and action.” She proposed to break through these calcified ideas. What she wished to do, she declared, “is to create for the reader another image of the city,” one drawn not from the imagination, hers or anyone else’s, but from real life, more compelling because truer. She was pushing far beyond those mechanical-sounding “five factors of the city” that had bogged down her first letter. And now she just came out and said it, unabashedly: she wanted her book to “open the reader’s eyes to a different way of looking at the city.”

The two letters to Gilpatric together expressed Jane’s thinking. But they were business documents, too, sometimes explicitly so, talking dollars and cents. Toward the end of the first letter, Jane laid out how she expected to manage financially while writing the book—eight months living on the Rockefeller grant, plus an “advance which I hope to get from

an interested publisher” for the final month. Gilpatric knew by now that

this “interested” publisher was no mere hope or possibility.

His name was Jason Epstein.

A Boston native and Columbia University graduate, Epstein, at age thirty, was already something of a publishing wunderkind as originator of the “quality paperback.” Paperback books went back to the 1930s and before, but in the 1950s they were invariably known for their cheap paper and their affinity for bodice-rippers and adventure yarns. At the other end of publishing were handsomely produced hardcover books, like those Epstein’s own house, Doubleday, produced. Into this gap stepped Epstein’s Anchor Books, the first “quality paperback” imprint—good books, good paper, intermediate prices. In the spring of 1958, Epstein had heard from Nathan Glazer about Jane’s article in

Fortune

and soon the whole series was a book,

The Exploding Metropolis

, first as Doubleday hardcover, then as Anchor paperback.

Whyte and Glazer

both urged Jane to talk to Epstein about a book of her own based on ideas she’d expressed in “Downtown Is for People.” She did so, and, as Gilpatric recorded in a June 26, 1958, memo, Epstein “expressed enthusiastic interest.” He offered her an advance of $1,500—modest, certainly, but more than she had expected.

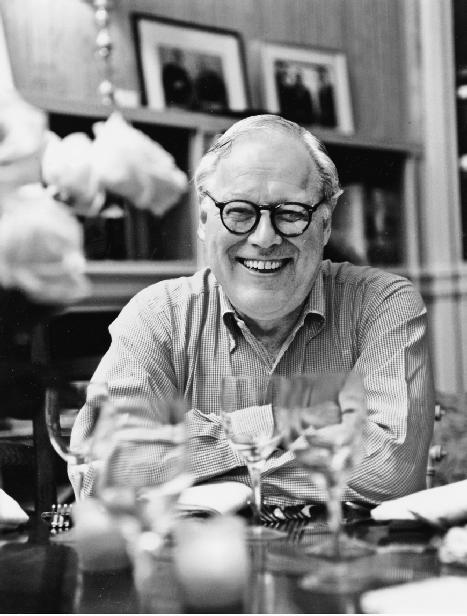

Jason Epstein, Jane’s editor at Random House from 1958 on and a friend for the rest of her life

Credit 16

Things were heating up. The philanthropic gears were turning. On July 7, Gilpatric wrote Jane, thanking her for the “

clearer and better composed picture of the book you want to write.”

On July 13, Jane responded to Gilpatric’s request for

a professional biography with a single-page document, together with a one-page addendum listing the city-themed articles she’d written for

Forum.

On July 23,

Forum

formally granted her a leave of absence to write the book.

On July 29, Gilpatric wrote

Lewis Mumford, asking for his frank assessment of Jane’s project. Three days later, he heard back. “I first came across her at a conference a few years ago,” he wrote, referring to her Harvard talk.

She made a brief address so pointed and challenging and witty, so merciless to the accepted clichés and so packed with fresh ideas that I felt like cheering; and did in fact cheer when called upon to make a few remarks at the end of the conference. Her direct, first-hand method of attack, and her common-sense judgments are worth whole filing cases of what is sometimes too respectfully called research.

And, he concluded,

I regard her purpose as important and her competence to carry it through indisputable; all the more because I am confident that her results will challenge a good deal of current practice. You will look far before you find a more worthy applicant in this field.

With that, and that alone, Jane’s good graces at the Rockefeller were probably assured. But Gilpatric was taking no chances; he had written to others as well for responses to Jane’s project. During August, he heard from Holly Whyte, who was, of course, “

wholeheartedly enthusiastic.” From Christopher Tunnard, of Yale, who was not; he dismissed Jane’s project as “

grandiose and vague.” From Catherine Bauer, the public housing expert, whom Jane had edited at

Forum:

“

I’d back Jane Jacobs if I were you,” she led off her response. “She’s a good writer, sensitive and imaginative.” But Bauer did offer one caveat:

Don’t let her get bogged down with academic theorizing or too much would-be scientific research. That isn’t her game and she probably knows it, but strange things sometimes happen to good creative popular writers when they get a Foundation grant!

In early September, Jane learned that her Rockefeller grant had been approved. She was grateful, she wrote Gilpatric on the 15th, for helping her do the book in the first place, but even more for helping her to understand what “I can do and want to do which might turn out to have

some general usefulness.”

CHAPTER 12

A MANUSCRIPT TO SHOW US

I

T WAS JUNE

1959, nine months into her Rockefeller grant, and Jane was in trouble, running way behind, flirting with despair over time and money.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

could seem so much the product of Jane’s distinctive intellect that one might forget that it was “researched”; she visited cities, talked to people, traded ideas with experts, gathered statistics, sought out pointed bits of knowledge. The previous October, Gilpatric noted that Jane had “

completed plans for a series of discussions” with urban thinkers, including James Rouse, a shopping center developer in Baltimore; and William Slayton, involved in developing southeast Washington, D.C. She had recently attended a Rockefeller-sponsored conference in Rye, New York, on urban design criticism that had also drawn Louis Kahn, Kevin Lynch, Ian McHarg, and Lewis Mumford, among other notables. In a memo about six weeks later, Gilpatric observed that Jane had plenty of “

opinions and critical comments about Los Angeles and San Francisco,” yet had never been to either city; she hoped soon to correct that lapse. In St. Louis, the Washington University architecture professor Roger Montgomery showed her around a fifty-seven-acre housing complex of Corbusian buildings—much celebrated in the architectural press when it went up a few years earlier—known as Pruitt-Igoe.

It was all interesting. It was all worthwhile. And it all took time.

While in Boston, Jane met Harvard and MIT faculty who had learned of her grant and suggested she drop by for lunch. Turns out, as Jane recounted, they knew exactly how she needed to proceed:

They had it all figured out—how I should use that grant, how I should use my time. They had decided what they wanted done and they were treating me as if I was a graduate student. What they actually wanted me to do was make up a questionnaire and give it to people in some middle-income sterile project somewhere, to find out what they didn’t like. Then I was to make tables of it. They had it all worked out, what I should do. So I listened to them and remained polite, but I couldn’t wait to get out of there.

Years later, the memory of that lunch could move her to fury. “Disgusting!,” she’d call the intellectually banal project they had in mind for her. “That’s what their interest in cities was, just junk like that.”

Boston also introduced her to the young sociologist Herbert Gans. The previous October, Gans had moved with his wife into a $42-a-month apartment in Boston’s West End. It was the last days of that Italian working-class neighborhood before it was cut down for new modernist apartment buildings with fine views of the State House dome on Beacon Hill. Gans, thirty, had done some of his earliest studies in a Chicago suburb known as Park Forest, where Holly Whyte, Jane’s champion at

Fortune

, had done research for

The Organization Man.

So when one day Whyte called to tell him “about how this

woman wanted to see the North End,” he obliged.