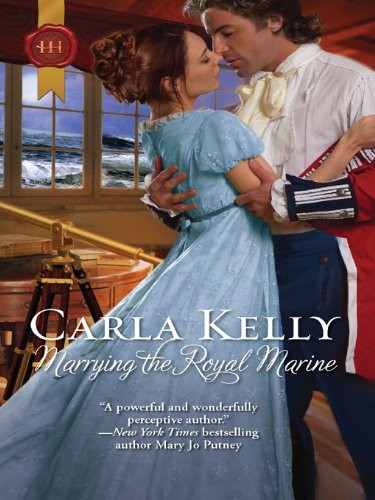

Marrying the Royal Marine

Read Marrying the Royal Marine Online

Authors: Carla Kelly

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Romance, #Historical, #Regency, #Historical Romance, #Series, #Harlequin Historical

“Miss Brandon, the surgeon has declared that no one dies of seasickness. You will not be the first, and certainly not on my watch,” Hugh said firmly.

“I. Would. Rather. Die.”

At least she was alert. “It’s not allowed in the Royal Navy, my dear,” he told her kindly. “When Private Leonard returns, I am going to tidy you, find you another nightgown and put you in my sleeping cot.”

She started to cry in earnest then, which was a sorry sight, since there were no tears. “Leave me alone,” she pleaded.

“I can’t leave you alone. I would do anything to spare you embarrassment, Miss Brandon, but you must be tended to.”

“The surgeon?”

“Busy. My dear, you’ll just have to trust me, because there is no one else.”

Marrying the Royal Marine

Harlequin

®

Historical #998—June 2010

Praise for Carla Kelly, recipient of a Career Achievement Award from

RT Book Reviews

and winner of two RITA

®

Awards

“A powerful and wonderfully perceptive author.”

—

New York Times

bestselling author Mary Jo Putney

“A wonderfully fresh and original voice…”

—

RT Book Reviews

“Kelly has the rare ability to create realistic yet sympathetic characters that linger in the mind. One of the most respected…Regency writers.”

—

Library Journal

“Carla Kelly is always a joy to read.”

—

RT Book Reviews

“Ms. Kelly writes with a rich flavor that adds great depth of emotion to all her characterizations.”

—

RT Book Reviews

C

ARLA

K

ELLY

Marrying the Royal Marine

Available from Harlequin

®

Historical and CARLA KELLY

Beau Crusoe

#839

*

Marrying the Captain

#928

*

The Surgeon’s Lady

#949

*

Marrying the Royal Marine

#998

To Lynn and Bob Turner, former U.S. Marines.

Semper Fi

to you both.

Contents

Prologue

Stonehouse Royal Marine Barracks, Third Division, Plymouth—May 1812

B

lack leather stock in hand, Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Philippe d’Anvers Junot, Royal Marine, stared into his mirror and decided his father was right: he was lonely.

Maybe early symptoms were the little drawings that deckled Hugh’s memorandum tablet during endless meetings in the conference room at Marine Barracks. As Colonel Commandant Lord Villiers covered item after item in his stringent style, Hugh had started drawing a little lady peeking around the edge of her bonnet. During one particularly dull budget meeting, he drew a whole file of them down the side of the page.

Hugh gazed more thoughtfully into the mirror, not bothered by his reflection—he knew his height, posture, curly brown hair, and nicely chiselled lips met the demands of any recruiting poster—but by the humbling knowledge that his father still knew him best.

He had written to his father, describing his restlessness and his dissatisfaction with the perils of promotion. While flattering, the promotion had bumped him off a ship of the line and into an office.

I know I should appreciate this promotion

, he had written,

but, Da, I am out of sorts. I’m not sure what I want. I’m sour and discontented. Any advice would be appreciated. Your dutiful, if disgruntled, son.

A week later, he had read Da’s reply over breakfast. He read it once and laughed; he read it again and pushed back his chair, thoughtful. He sat there longer than he should have, touched that his father had probably hit on the matter: he was lonely.

Damn this war

, he had thought then. The words were plainspoken as Da was plainspoken:

My dear son, I wrote a similar letter to your grandfather once, before I met your mother, God rest her soul. Son, can ye find a wife?

‘That takes more time than I have, Da,’ he had said out loud, but Da was probably right. Lately, when he attended the Presbyterian church in Devonport, he found himself paying less attention to the sermon and more attention to husbands, wives, and children sitting in the pews around him. He found himself envying both the comfortable looks of the couples married longest, and the shy hand-holdings and smouldering glances of the newly married. He tried to imagine the pleasure of marrying and rearing children, and found that he could not. War had ruined him; perhaps Da wasn’t aware of that.

It was food for thought this May morning, and he chewed on it as he took advantage of a welcome hiatus from a meeting—the Colonel Commandant’s gout was dictating a start one hour later than usual—and took himself to Stonehouse Naval Hospital. He had heard the jetty bell clanging late last night, and knew there would be wounded Marines to visit.

The air was crisp and cool, but threatening summer when he arrived at Block Four, where his friend Owen Brackett worked his surgeon’s magic on the quick and nearly dead. He found Owen on the second floor.

The surgeon turned to Hugh with a tired smile. ‘Did the jetty bell wake you?’

Hugh nodded. ‘Any Marines?’

‘Aye. If you have a mind to visit, come with me.’

Hugh followed Brackett down the stairs into another ward. With an inward sigh, he noted screens around several beds.

‘There was a cutter returning from Surgeon Brittle’s satellite hospital in Oporto. The cutter was stopped at sea by a frigate with some nasty cases to transfer,’ Owen said. ‘Seems there was a landing attempted farther north along the Portuguese coast. Sit.’

He sat, never used to ghastly wounds, and put his hands on the man’s remaining arm, which caused the Marine’s eyes to flicker open.

‘Meet Lieutenant Nigel Graves, First Division,’ Brackett whispered before leaving.

‘From Chatham?’ Hugh asked, putting his lips close to the man’s ear.

‘Aye, sir. Serving on…

Relentless

.’ It took ages for him to get out the words.

‘A regular mauling?’ he asked, his voice soft. ‘Take your time, Lieutenant. We have all day.’ He didn’t; the Lieutenant didn’t. It was a serviceable lie; both knew it.

Lieutenant Graves tried to sit up. Hugh slipped his arm under the young man’s neck. ‘What were you doing?’

‘Trying to land at Vigo.’

‘A one-ship operation?’

‘Four ships, sir.’ He sighed, his exasperation obvious. ‘We didn’t know each other! Who was in charge when the Major died?’ He closed his eyes. ‘It was a disaster, sir. We should have been better.’

Hugh could tell he wanted to say more, but Lieutenant Graves took that moment to die. Hugh gently lowered him to the cot. He was still sitting there when Owen Brackett returned, enquired about the time of death from him, and wrote it on the chart.

‘A botched landing at Vigo,’ Hugh said. ‘Uncoordinated Marines working against each other, when all they wanted to do was fight! I’ve heard this before.’

‘It makes you angry,’ Owen said.

‘Aye.’ Hugh smoothed down the Lieutenant’s hair. ‘Each company on each vessel is a well-oiled machine, because we train them that way. Put one hundred of them on a ship of the line, and you have a fighting force. Try to coordinate twenty-five here or fifteen there from three or four frigates operating in tandem, and it can be a disaster.’

The surgeon nodded. ‘All they want to do is their best. They’re Marines, after all. We expect no less.’

Hugh thought about that as he took the footbridge back over the stream to the administration building of the Third Division. He was never late to anything, but he was late now.

The meeting was in the conference room on the first floor. He stopped outside the door, hand on knob, as a good idea settled around him and blew away the fug. Why could someone not enquire of the Marines at war how they saw themselves being used in the Peninsula?

‘You’re late, Colonel Junot,’ his Colonel Commandant snapped.

‘Aye, my lord. I have no excuse.’

‘Are those

stains

on your uniform sleeve?’

Everyone looked. Hugh saw no sympathy. ‘Aye, my lord.’

Perhaps it was his gout; Lord Villiers was not in a forgiving mood. ‘Well? Well?’

‘I was holding a dying man and he had a head wound, my lord.’

His fellow Marine officers snapped to attention where they sat. It might have been a tennis match; they looked at the Commandant, as if on one swivel, then back at Hugh.

‘Explain yourself, sir,’ Lord Villiers said, his voice calmer.

‘I visited Stonehouse, my lord.’ He remained at attention. ‘Colonel, I know you have an agenda, but I have an idea.’

Chapter One

L

ord Villiers liked the idea and moved on it promptly. He unbent enough to tell Hugh, as he handed him his orders, ‘This smacks of something I would have done at your age, given your dislike of the conference table.’

‘I, sir?’

‘Belay it, Colonel Junot! Don’t bamboozle someone who, believe it or not, used to chafe to roam the world. Perhaps we owe the late Lieutenant Graves a debt unpayable. Now take the first frigate bound to Portugal before I change my mind.’

Hugh did precisely that. With his dunnage stowed on the

Perseverance

and his berth assigned—an evil-smelling cabin off the wardroom—Hugh had dinner with Surgeon Brackett on his last night in port. Owen gave him a letter for Philemon Brittle, chief surgeon at the Oporto satellite hospital, and passed on a little gossip.

‘It’s just a rumour, mind, but Phil seems to have engineered a billet for his sister-in-law, a Miss Brandon, at his hospital. He’s a clever man, but I’m agog to know how he managed it, if the scuttlebutt is true,’ Brackett said. ‘Perhaps she is sailing on the

Perseverance

.’

‘Actually, she is,’ Hugh said, accepting tea from Amanda Brackett. ‘I’ve already seen her.’

‘She has two beautiful sisters, one of whom took leave of her senses and married Phil Brittle. Perhaps your voyage will be more interesting than usual,’ the surgeon teased.

Hugh sipped his tea. ‘Spectacles.’

‘You’re a shallow man,’ Amanda Brackett said, her voice crisp.

Hugh winced elaborately and Owen laughed. ‘Skewered! Mandy, I won’t have a friend left in the entire fleet if you abuse our guests so. Oh. Wait. He’s a Royal Marine. They don’t count.’

Hugh joined in their laughter, at ease with their camaraderie enough to unbend. ‘I’ll have you know I took a good look at her remarkable blue eyes, and, oh, that auburn hair.’

‘All the sisters have it,’ Amanda said. ‘More ragout?’

‘No, thank you, although I am fully aware it is the best thing I will taste until I fetch the Portuguese coast in a week or so.’ He set down his cup. ‘Miss Brandon is too young to tempt me, Amanda. I doubt she is a day over eighteen.’

‘And you are antiquated at thirty-seven?’

‘I am. Besides that, what female in her right mind, whatever her age, would make a Marine the object of her affection?’

‘You have me there, Colonel,’ Amanda said promptly, which made Owen laugh.

She did have him, too, Hugh reflected wryly, as he walked from Stonehouse, across the footbridge, and back to the barrack for a final night on shore.

Perhaps I am shallow

, he considered, as he lay in bed later. Amanda Brackett was right; he was vain and shallow. Maybe daft, too. He lay awake worrying more about his assignment, putting Miss Brandon far from his mind.

Hugh joined the

Perseverance

at first light, the side boys lined up and the bosun’s mate piping him aboard. His face set in that no-nonsense look every Marine cultivated, and which he had perfected, he scanned the rank of Marines on board. He noted their awed recognition of his person, but after last night’s conversation, he felt embarrassed.

He chatted with Captain Adney for only a brief minute, knowing well that the man was too busy for conversation. Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed Miss Brandon standing quietly by the binnacle, her hands clasped neatly in front of her, the picture of rectitude, or at the very least, someone just removed from the schoolroom herself. Amanda Brackett had said as much last night. She was a green girl.

He had to admit there was something more about Miss Brandon, evidenced by the two Midshipmen and Lieutenant grouped about her, appearing to hang on her every word. She had inclined her head to one side and was paying close attention to the Lieutenant. Hugh smiled. He could practically see the man’s blush from here on the quarterdeck.

Miss Brandon, you are obviously a good listener

, he thought.

Perhaps that compensates for spectacles.

The moment the thought swirled in his brain, he felt small again.

What a snob I am

, he concluded, turning his attention again to Captain Adney.

‘…passage of some five days, Colonel, if we’re lucky,’ he was saying. ‘Is it Oporto or Lisbon for you?’

It scarcely mattered, considering his

carte blanche

to wander the coastline on his fact-finding mission. Perhaps he should start at Lisbon. ‘Oporto,’ he said. He knew he had a letter for Surgeon Brittle, Miss Brandon’s brother-in-law, but he also knew he could just give it to her and make his way to Lisbon, avoiding Oporto altogether. ‘Oporto,’ he repeated, not sure why.

‘Very well, sir,’ Captain Adney told him. ‘And now, Colonel, I am to take us out of harbour with the tide. Excuse me, please.’

Hugh inclined his head and the Captain moved towards his helmsman, standing ready at the wheel. Hugh watched with amusement as the flock around Miss Brandon moved away quickly, now that their Captain was on the loose and prepared to work them.

Hardly knowing why, Hugh joined her. He congratulated himself on thinking up a reason to introduce himself. He doffed his hat and bowed. ‘Miss Brandon? Pray forgive my rag manners in introducing myself. I am Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Junot, and I have some business you might discharge for me.’

She smiled at him, and he understood instantly why the Lieutenant and Midshipmen had been attracted to her like iron filings to a magnet. She had a direct gaze that seemed to block out everything around her and focus solely on the object of her interest. He felt amazingly flattered, even though she was doing nothing more than giving him her attention. There was nothing coy, arch or even flirtatious about her expression. She was so completely

present

. He couldn’t describe it any better.

She dropped him a deep curtsy. Considering that it was high summer and she wore no cloak, this gave him ample opportunity to admire her handsome bosom.

‘Yes, Colonel, I am Miss Brandon.’

As he put on his hat again, her eyes followed it up and she did take a little breath, as though she was not used to her present company. He knew she must be familiar enough with the Royal Navy, considering her relationship to a captain and a surgeon, but he did not think his splendid uniform was ringing any bells.

‘I am a Marine, Miss Brandon,’ he said.

‘And I am a hopeless landlubber, Colonel,’ she replied with a smile. ‘I should have known that. What can I do for you?’

What a polite question

, he thought.

It is almost as if I were infirm. She is looking at me as though I have a foot in the grave, no teeth, and more years than her brothers-in-law combined. What an ass I am.

Feeling his age—at least every scar on his body had not started to ache simultaneously—he nodded to her. ‘Miss Brandon, I have been charged by Surgeon Owen Brackett to take a letter to your brother-in-law in Oporto. I suppose that is why I sought to introduce myself, rather than wait for someone else—who, I do not know—to perform that office.’

That is marvellously lame

, he thought sourly, thinking of the gawking Midshipmen who had so recently claimed her attention, and mentally adding himself to their number.

The deferential look left her face. ‘Taking a letter to my brother-in-law is a pleasant assignment, sir. I am headed to the same place. Do you know Surgeon Brittle?’

‘Not yet.’

‘If you are too busy to discharge your duty, I can certainly relieve you of the letter, Colonel,’ she told him.

‘I am going there, too.’

He could think of nothing more to say, but she didn’t seem awkwardly waiting for conversation. Instead, she turned her back against the rail to watch the foretopmen in the rigging, preparing to spill down the sails and begin their voyage. It was a sight he always enjoyed, too, so he stood beside her in silence and watched. Although he had scarce acquaintance with the lady beside him, he felt no urge to blather on, in the way that newly introduced people often do.

The

Perseverance

began to move, and he felt his heart lift, so glad he was to be at sea again and not sitting in a conference room. He would range the coast, watch his Marines in action, interview them, and possibly formulate a way to increase their utility. With any luck, he could stretch his assignment through the summer and into autumn.

‘I have never sailed before,’ Miss Brandon said.

‘You’ll get your sea legs,’ he assured her, his eyes on the men balancing against the yardarms. He hoped it wasn’t improper to mention legs to a lady, even the sea kind.

In a few more minutes, she went belowdeck. He watched Marines working the capstan with the sailors, and others already standing sentry by the water butt and the helm. He nodded to the Sergeant of Marines, who snapped to attention, and introduced himself as the senior non-commissioned officer on board. A thirty-six-gun frigate had no commissioned officer. Hugh explained his mission and told the man to carry on.

He stayed on deck until the

Perseverance

tacked out of Plymouth Sound and into the high rollers of the Channel itself. He observed the greasy swell of the current and knew they were in for some rough water. No matter—he was never seasick.

He went belowdeck and into his cabin, a typical knocked-together affair made of framed canvas, which was taken down when the gundeck cleared for action. His sleeping cot, hung directly over the cannon, was already swaying to the rhythm of the Atlantic Ocean. He timed the swell and rolled into the cot for a nap.

Because Miss Brandon had admitted this was her first sea voyage, Hugh was not surprised when she did not appear for dinner in the wardroom. Captain Adney had the good sense to give her the cabin with actual walls, one that probably should have gone to a Lieutenant Colonel of Marines, had a woman not been voyaging. The Sergeant had posted a sentry outside her door, which was as it should be. There were no flies growing on this little Marine detachment, and so he would note in his journal.

There was no shortage of conversation around the wardroom table. The frigate’s officers let him into their conversation and seemed interested in his plan. Used to the sea, they kept protective hands around their plates and expertly trapped dishes sent sliding by the ship’s increasingly violent motion. When the table was cleared and the steward brought out a bottle, Hugh frowned to hear the sound of vomiting from Miss Brandon’s cabin.

The surgeon sighed and reached for the sherry as it started to slide. ‘Too bad there is no remedy for

mal de mer

,’ he said. ‘She’ll be glad to make land in a week.’

They chuckled, offered the usual toasts, hashed over the war, and departed for their own duties. Hugh sat a while longer at the table, tempted to knock on Miss Brandon’s door and at least make sure she had a basin to vomit in.

She didn’t come out at all the next day, either.

Poor thing

, Hugh thought, as he made his rounds of the Marine Privates and Corporals, trying to question them about their duties, taking notes, and wondering how to make Marines naturally wary of high command understand that all he wanted was to learn from them. Maybe the notion was too radical.

Later that night he was lying in his violently swinging sleeping cot, stewing over his plans, when someone knocked on the frame of his canvas wall.

‘Colonel, Private Leonard, sir.’

Hugh got up in one motion, alert. Leonard was the sentry outside Miss Brandon’s door. He had no business even crossing the wardroom, not when he was on duty.

Your Sergeant will hear from me, Private

, he thought, as he yanked open his door.

‘How dare you abandon your post!’ he snapped.

If he thought to intimidate Private Leonard, he was mistaken. The man seemed intent on a more important matter than the potential threat of the lash.

‘Colonel Junot, it’s Miss Brandon. I’ve stood sentinel outside her door for nearly four hours now, and I’m worried.’ The Private braced himself against the next roll and wiggle as the

Perseverance

rose, then plunged into the trough of a towering wave. ‘She was puking and bawling, and now she’s too quiet. I didn’t think I should wait to speak until the watch relieved me, sir.’

Here’s one Marine who thinks on his feet

, Hugh thought, as he reached for his uniform jacket. ‘You acted wisely. Return to your post, Private,’ he said, his voice normal.

He had his misgivings as he crossed the wardroom and knocked on her door. Too bad there was not another female on board. He knocked again. No answer. He looked at Private Leonard. ‘I go in, don’t I?’ he murmured, feeling suddenly shy and not afraid to admit it. There may have been a great gulf between a Lieutenant Colonel and a Private, but they were both men.

‘I think so, sir,’ the Private said. ‘Do you have a lamp?’

‘Go get mine.’

He opened the door and was assailed by the stench of vomit. ‘Miss Brandon?’ he called.

No answer. Alarmed now, he was by her sleeping cot in two steps. He could barely see her in the gloom. He touched her shoulder and his hand came away damp. He shook her more vigorously and was rewarded with a slight moan.

No one dies of seasickness

, he reminded himself. ‘Miss Brandon?’ he asked again. ‘Can you hear me?’

Private Leonard returned with his lantern, holding it above them in the tiny cabin. The light fell on as pitiful a specimen of womanhood as he had ever seen. Gone was the moderately attractive, composed young lady of two days ago. In her place was a creature so exhausted with vomiting that she could barely raise her hands to cover her eyes against the feeble glow of the lantern.

‘I should have approached you sooner, sir,’ Private Leonard said, his voice full of remorse.

‘How were you to know?’ he asked. ‘We officers should have wondered what was going on when she didn’t come out for meals. Private, go find the surgeon. I am relieving you at post.’

‘Aye, aye, Colonel.’

Uncertain what to do, Hugh hung the lantern from the deck beam and gently moved Miss Brandon’s matted hair from her face, which was dry and caked. She didn’t open her eyes, but ran her tongue over cracked lips. ‘You’re completely parched,’ he said. ‘Dryer than a bone. My goodness, Miss Brandon.’