Faith and Betrayal (14 page)

Though her home had not been disturbed, there had been no crops sown during the summer, so the following winter was one of severe hunger. Jean Rio, like all the other women in her community, spent hours bent over a washboard, perspiring over hot irons, sewing by candlelight, or tilling the scorched earth, her genteel past fading into a distant memory. Nothing was an equalizer like pioneer life.

Soon afterward her sons Charles Edward and John, now twenty-one and seventeen years old respectively, fled Zion. Jean Rio encouraged them, though the plans for escape were of necessity kept secret from all neighbors, friends, and acquaintances, and especially from their fundamentalist brother, William. Anguished at their going, she thought of joining them, but she kept no written record of her feelings at the time—so dangerous would it have been for her if her apostasy had been uncovered. In any case, church leaders would view her with suspicion as soon as knowledge of her sons’ flight became apparent, and would grill her incessantly about her own depth of conviction.

“The brothers sneaked away from Utah in the middle of the night on two horses,” according to a descendant of one of the men. They would tell their future children that they knew if they were caught departing the territory they would be put to death. “Brigham Young didn’t like people leaving, especially if they took horses.” After a harrowing journey over the Sierra Nevada mountain range they arrived safely in San Francisco. “They could not stand poverty any longer so ran away from it,” wrote their mother. She considered accompanying them to California but found herself torn between the misery of the life she knew and the unknown of yet another frontier. She had set out for “the city in the tops of the mountains” with seven children as part of what one historian has called “a pageant of divine destiny.” Now, some nine years later, two sons were dead and two sons had struck out on their own to the edge of America.

“My 20-acre farm turned out to be a mere salaratus patch, killing the seed which was sown instead of producing a crop,” Jean Rio recalled years later, writing an addendum to her diary. Admitting defeat, she deserted her land, moving into a “small log house” in Ogden City to learn dressmaking. “I have tried to do my best in the various circumstances in which I have been placed,” she wrote. “I came here in obedience to what I believed to be a revelation of the most high God, trusting in the assurance of the Missionaries whom I believed to have the spirit of truth. I left my home, sacrificed my property, broke up every dear association, and what was and is yet dearer than all, left my beloved native land. And for what? A bubble that has burst in my grasp. It has been a severe lesson, but I can say it has led me to lean more on my Heavenly Father and less on the words of men.”

CHAPTER EIGHT

Through the Veil

WITH A GENIUS for colonizing unmatched in the annals of the West, Young had methodically expanded his domain throughout the 1850s. The English converts had included mostly laborers and stonemasons; the Americans were primarily farmers. But Young needed weavers, tailors, shoemakers, and watchmakers to build a civilized society in such isolation, and he turned to Scandinavia, Scotland, and Wales to help fill that need. To cultivate the arid land and forge tools and implements he needed more farmers and mechanics. So he shrewdly turned his attention to Denmark, a country where most men labored under aristocratic landowners and where sectarian schisms were destroying the once-solid Lutheran unity. As Young also knew, virtually all Danish adults were literate, and all the men served six years in the Danish army, which would have prepared them well for the demands of building the “City of God.”

Young had sent missionaries to Denmark to preach God’s command to gather in Zion, where the finest land could be had merely for the price of a survey. To become lords of the soil was a powerful, irresistible argument to the peasantry of Denmark at a time when their prospects of owning land were nil. The plea of the missionaries to leave the Old World and its troubles for something wholly new and exhilarating was even more effective than Young had anticipated. The highly educated, exceedingly healthy, and unusually skilled Danes, donning their fine homespun clothes, wooden shoes, and woolen socks, migrated to Zion in droves, the Danish women no less courageous or enthusiastic than the men. “The monotony of a man’s life was as nothing compared to a woman’s,” writes Icelandic author Halldór Laxness in describing the mundane gloom of Scandinavian existence at the time. Thousands of new converts would make their way to Utah. “The Danes, proverbially reluctant to sail out farther than they could row back, and traditionally considered poor pioneers,” writes a historian of the movement, “nevertheless, as Mormons, left their homeland in years of actual prosperity to become hardy grass-roots settlers.”

Nicolena Bertelsen, a young Danish girl, would be swept up in this fervor. Her destiny to become a plural wife—and Jean Rio Baker’s daughter-in-law—thousands of miles away in a foreign land was utterly devoid of free will. Born in Denmark on January 26, 1845, Nicolena was the seventh child of Niels and Maren Bertelsen. The Bertelsen family home was a white cottage on the moorland where Niels tilled the rolling heath for the wealthy landlord who lived in a manor house nearby. Though farming and fishing were his mainstays, Niels also hunted swans. Maren would pluck the soft down from the birds’ breasts to make pillows and comforters for their ten children.

Comprising the Jutland Peninsula and hundreds of mostly uninhabited islands, Denmark was a small dominion of northern Europe surrounded by water except at Jutland’s forty-two-mile border with Germany. With its blue lakes and white coastlines, the sea-level landscape was home to some of history’s more savage people. From the ancient Cimbri and Teutons who raided Europe to the later Vikings—fierce pirates and warriors who terrorized England, Ireland, Germany, France, and Russia for three hundred years—the Danes were notoriously courageous and cruel. By the fifteenth century, the once heavily forested land was completely denuded at the behest of kings seeking timber for Danish ships. The ravaged expanse acquired a sad emptiness, dotted as it was with wind-mills, thatched roofs, and massive stone castles.

But the nineteenth-century Denmark of the Bertelsens was known more for the gentle fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard than for the brutality of its past. Having lost Norway to Sweden in 1814 during the Napoleonic wars, Denmark had fallen into a thirty-year depression, only to emerge as a European capital of art and literature. Its radical educational reform—designed to prepare the peasant for his struggle in political and economic life—required that every boy and girl between the ages of six and fourteen attend school. This system of compulsory education for all was the most advanced in the world, ushering in Denmark’s golden age and having far-reaching consequences for communities in the American West settled by Danes.

Niels and Maren were typical of their time and place, exhibiting nothing of the religious fundamentalism that would define their midlife years. Though Maren was—like 97 percent of the Danish population—an orthodox Lutheran, Niels preferred the almanac to the Bible and relentlessly teased his wife about her piety. But when Mormon missionaries reached the Bertelsens’ tiny village of Staarup in 1852—three years after Jean Rio Baker and her husband were converted in England—Maren was an eager convert to their message of hope and fulfillment. “In Scandinavia, Zion was proclaimed in a vigorous literature ranging from the sober and moralizing to the extravagant and apocalyptic that sometimes failed to distinguish between Zion as metaphor,” according to a scholar of Scandinavian immigration, “ . . . identifying Deseret with Zion of the Psalms.” Whether allegory or reality, the missionaries portrayed America as the land of promise where the most optimistic dreams could be realized. At the heart of the Mormon movement was the “gathering” of converts to Zion, where “they would never know themselves otherwise than saints.” The serious-minded Maren was convinced after only one meeting with the missionaries, while Niels remained reluctant. But when their landlord evicted them from their home of twenty-one years for hosting the Mormons, Niels was so outraged by the injustice that he too joined the faith. In 1853 the entire Bertelsen family was baptized in haste and secrecy and the children began departing one by one for the new Zion.

Nicolena was the fourth child to leave Denmark, entrusted to the care of two missionaries returning to Utah. That November, the blue-eyed eight-year-old swathed in bulky warm clothing, a peasant handkerchief tied over her yellow curls, waited on a busy wharf. Arm in arm with her playmate and sister Ottomina, who would stay behind, she stood clutching a bundle of belongings. Terrified at the reality of the solo journey and mystified by the talk of “salvation” and “Zion,” she felt helpless to challenge her parents.

Nicolena had tearfully begged her mother to let her take her favorite doll, but the stern Maren refused, saying only necessities could be taken—a denial Nicolena remembered her entire life. She watched the deck crews, wishing that her parents would suddenly change their minds. Instead, Maren told her to be a good girl and to pray. Stuffing a small Bible into her armload, Maren directed her to read from it every day. “Keep clean,” Nicolena remembered her mother telling her. “And wait on yourself, never be a burden to anyone. And never, never cry!”

Her childhood had been blissfully happy and she could not understand why her parents would want to change any of it. She loved going out with her father in the fishing boat as he hunted the wild birds and then making miniature down comforters for her dolls. She and Ottomina, so close in age, romped through the meadows after completing their chores, “digging in the sandy beaches, playing under the leafy boughs of the beech trees,” she would later recall.

Ottomina had saved her pennies to buy sweetcakes for Nicolena, and she now pressed them into her sister’s hand. Nicolena quickly brushed her tears away so her mother could not see. She later recalled that she had no appetite then, or for many weeks later, and the sweetcakes went uneaten.

Similar to Jean Rio before her, she spent three stormy months on the Atlantic Ocean. She was seasick and homesick, nauseated from the ship’s fare and unable to sleep on the hard beds. A fire on the boat threatened the entire company and a second ship responded to their distress signal, rescuing all on board. The ship docked in New York, and the spectacle of the city was unlike anything in Nicolena’s rural homeland. Lonely and miserable, Nicolena continued by rail to Chicago, and then on to St. Louis. She arrived in St. Louis in March 1854, having traveled by sea and land for four months. There, to her horror, the missionaries told her they could take her no farther. They turned her over to an employment agency and promised to inform her family of her whereabouts. Speaking only Danish and possessing no money, Nicolena was so overtaken with fear and despair that she would later reflect that all the trials she thenceforth endured paled in comparison.

Months passed with no word from Denmark or Utah. A wealthy family offered her a position as a babysitter, a job she would hold for two years. Though the family was kind and loving, teaching her English and offering her a permanent home with them, Nicolena maintained a single-minded determination to join other family members who had already made the voyage to Zion. She saved every cent she earned until she had enough to buy transportation on a Mississippi steamboat from St. Louis to Council Bluffs, which, she had been told, was the starting point for wagon trains heading to Utah.

Now ten years old and venturing alone into an unknown world, Nicolena found a handcart company assembling for the long trek west. But there was no place for a young girl without a family to watch over her. Touched by the Danish girl’s predicament, an emigrant offered to let her travel with his family in exchange for help with his pregnant wife. By this time, Nicolena’s emotional pain had healed and with a bit of maturity her fears had abated. She faced the journey with excitement, and later in life recalled the experience as “a glorious adventure” marred only by one terrifying episode. Once, when the company stopped for wagon repairs, an exhausted Nicolena fell asleep in a willow grove on the bank of a stream. She awakened to find herself alone, the handcart train so far ahead it was no longer visible. Crying and screaming, she began running on the prairie, following the train’s tracks. Suddenly she saw a horseman galloping toward her, and she assumed that he was an Indian warrior. Instead he was her rescuer—the rear guard of the company who had noticed she was missing. The guard lifted the girl onto the horse and calmed her. Convinced that her prayers had been answered, that divine intervention had plucked her from harm, she felt her first stirrings of faith. Perhaps her parents had been right, that God indeed would usher true believers to safety in the “city in the tops of the mountains.” In retrospect, the journey was idealized in her mind. “She was, after all, a child with a child’s natural happy outlook,” one of her daughters later recalled. “During the long trek west, the great outdoors, the lure of unaccustomed scenes and activities, and the knowledge that at last she was on her way to Zion made it almost entirely a glorious adventure.”

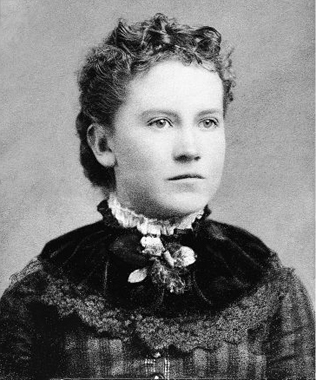

Nicolena thought it miraculous when she was reunited with her brother Lars and sister Letty, who had arrived before her and were settled in the south-central Utah community of Richfield. Letty oversaw Nicolena’s adolescence, helping her improve her English and continuing what Nicolena called her “book learning.” An eager student, Nicolena became proficient in the common pioneer pursuits of cleaning, combing, and spinning the raw wool from sheep, and weaving, dyeing, and sewing the cloth. “A lovely blonde with luxuriant honey-colored hair of the texture of spun silk,” as one account described her, she had a unique sense of style perhaps acquired from her years in cosmopolitan St. Louis. She became a talented seamstress and by the time she was fourteen years old was able to support herself as a dressmaker. “Good taste in her own dress and an inborn genius at sewing soon earned for her a reputation, from which she was able to earn many a dollar,” according to one account. In her spare time, she would join other young people in the wheat fields, spending hours at a time gathering the choice grasses. Resourceful and ingenious, she then braided wheat straw into plaits with which she decorated bonnets, and she sold the bonnets to the more affluent of the Saints.

At the age of nineteen she fell in love with a fellow Dane named Christian Christensen. But on April 21, 1866, Christensen was mortally wounded in an Indian uprising near Marysvale, Utah. Nicolena cared for him for six weeks and insisted on a deathbed wedding. Being “sealed” to him “for time and eternity” meant, according to Mormon doctrine, that she and any future children she bore would belong to him in the “hereafter.” Their love story became the subject of a ballad sung throughout Utah over the next century.

Grief-stricken upon her husband’s death, Nicolena took a job as a maid at the Richfield House hotel, owned by the well-to-do Englishman William George Baker and his wife, Hannah. The second-oldest son of Jean Rio, William had helped his mother farm in Ogden until Brigham Young ordered him to go south to help settle the community of Moroni in 1862, and then Richfield the following year. He was one of thirty-nine men chosen by Young to locate areas in Deseret that would sustain a growing Mormon population. The only son of Jean Rio’s to remain a practicing Mormon, he had been well rewarded by Brigham Young for his dedication. In addition to being a teacher and businessman, he held the lucrative patronage contract with the U.S. government to deliver mail in Utah Territory, ran a stagecoach line from Nephi to Panguitch, and practiced law. As the first settler in Richfield he set up a civil rather than a theocratic government.