Faith and Betrayal (17 page)

If Jean Rio and her last remaining Mormon son now disagreed about Mormon theology, church corruption, and the doctrine of polygamy, they apparently put such discord aside during her visit to his Richfield home. Ensconced at the gracious residence of William’s first wife, Hannah, Jean Rio determined to enjoy her son and his family for what she clearly believed would be the last time.

At the direction of Brigham Young, William had settled the picturesque little farming community of Richfield in Sevier County in 1863. By 1867 the Indian uprising that would become known as Utah’s Black Hawk War intensified, and the town was abandoned. William had relocated his wives, Hannah and Nicolena, and their numerous children to the community of Nephi, seventy-five miles north. They had remained there until 1872, when the fighting subsided and he could safely return his families to the two homes he had built for them in Richfield—Hannah’s large adobe and Nicolena’s dugout.

At the moment of Jean Rio’s last visit to Utah, the place seemed suddenly to occupy the front pages of newspapers around the country. While John Doyle Lee’s trial brought hundreds of journalists and federal officials into the territory, now too was polygamy bringing renewed and unwanted outside attention to the controversial theocratic enclave. Fanny Stenhouse, the Englishwoman and former Saint, had begun a nationwide lecture series promoting her new book-length exposé on the Mormon Church and polygamy,

Tell It All.

Harriet Beecher Stowe had written the preface to Stenhouse’s book, and the subject was arousing men and women throughout the country to demand that polygamy be eradicated.

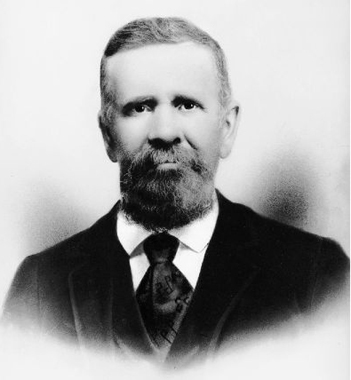

It would be but a few more years until William George Baker would be forced into hiding for his principles, seeking to escape the wrath of the U.S. marshals enforcing antipolygamy statutes. (Such enforcement was a condition for Utah statehood.) For now, he believed in the doctrine as the divine inspiration of Mormon prophets, and he practiced plural marriage openly, proudly, and enthusiastically. Considered an upright and noble man, courteous and kind—if perhaps a bit stern and dour for Jean Rio’s taste—William was one of the leaders of the community. “Make yourself an honest man, and then you may be sure there is one rascal less in the world” was his motto. A man who “never bamboozled or bribed,” as one account described him, he was a lawyer, hotelier, city councilman, justice of the peace, notary public, county assessor, and dramatist, and he held the coveted U.S. Postal Service contracts to deliver mail by Pony Express. Having inherited his father’s engineering aptitude, he devised a reservoir for melting snow and an ingenious irrigation system.

“Medium tall, with steel blue eyes, gray and black wavy hair, and a curly beard, which was always well trimmed,” as one of his daughters described him, “he stood very erect and had a portly bearing.” The daughter remembered his voice especially: “He had a deep baritone.” He was known for always riding a prancing black stallion, and in the Fourth of July and Pioneer Day parades he proudly donned the military uniform of Brigham Young’s controversial Nauvoo Legion, “epaulettes, sword, and all,” according to one account.

William George Baker, Jean Rio’s second-oldest son,

remained a staunchly loyal Mormon despite the apostasy

of his mother and brothers.

Jean Rio marveled at her forty-year-old son’s unwavering faith, the awesome financial burden of providing for two wives and the first fifteen of what would be twenty-three children, and the adversity he was willing to endure in pursuit of the everlasting. “Plucked from the lap of luxury and set down in a frontier land of staggering toil and comfortless surroundings,” recalled one of his children, not totally objectively, “he tackled his job and made good without excuses or regrets. His brothers couldn’t stand the privations and hardships and moved to California where life was not so hard. But William stayed with the religion he had embraced as a boy.” Soft-spoken, he had a gentility that commanded attention. Every Sunday morning, a granddaughter recalled, Jean Rio watched as he shined all the children’s shoes at both homes, placing them in a row, smallest to largest, “in a precise line like little black soldiers.”

“I remained among them one year and nine months, and had the chance of traveling over more of the Territory than I did during my eighteen years of residence there,” Jean Rio recalled in her diary. She helped William organize the first dramatic company in Richfield, producing their first play in an old meeting house. She sewed strips of unbleached muslin together for a stage curtain. Using lampblack, soot, and other vegetable dyes that she mixed with oil, she painted a scenic landscape of flowers and shrubs, and she hung the curtain from a stout cottonwood pole. She then acted in the first play produced there,

The

Lady of Lyons,

in which William starred in the role of Claude Melnotte. A perennial favorite of Victorian theater, the Edward Lytton play, set in post-Revolution France, was a sophisticated romantic comedy about the pretensions of class.

Still, for all the lightheartedness and laughter, Jean Rio, almost sixty-seven, returned to Antioch with mixed feelings: “In April 1877 I came back to California, and though I left Utah with regret, feeling sure that I should never see my dear ones there again on Earth, still, with much thankfulness that all was well with them,” she wrote later.

Three years after her visit to Utah, on May 8, 1880, she penned her final entry in the surviving diary.

I am seventy years old this day. Well may I say, “hitherto hath the Lord helped me.” I have good health and am spending my time among my children, sometimes at one house, sometimes at another. My boys have met with many disappointments, many trials, not the least has been the death of Chauncy, Walter’s youngest son. The rest of the family are well, and still are working on, hoping for better times. I can truly say, I have but one wish unfulfilled, and that is that I may live to see every one of my children and grandchildren faithful members of the Kingdom of God. I cannot expect to see many more birthdays, and as every hour brings me nearer to the final one, I feel to say with Toplady [the famous eighteenth-century British clergyman and hymnist]:

When I draw this fleeting breath,

When my eyelids close in death

When I soar to worlds unknown

And behold the judgment throne,

Rock of Ages, shelter me,

Let me hide myself in Thee.

EPILOGUE

Peace at Last

JULY 25, 1883

From Henry Walter Baker, Los Medanos, California

To William George Baker, Richfield, Utah

I am sorry to be obliged to write you this time in a not very happy frame of mind. Yesterday was my 50th birthday and I had the melancholy task to perform, of burying Dear Mother. She died quite suddenly on the night of the 21st at Los Gatos. I received a telegram Sunday noon and started immediately, to bring home her remains. Yesterday I placed her in the [Oddfellows] burying ground, near Antioch, and alongside of my Chauncy.

This trouble, although looked for for a good while, seemed to be a surprise after all. She had a malignant cancer and suffered a very great deal, and prayed for her release many a time, and it is a great blessing to her, I am sure, to be saved from lingering any longer. She was a member of the Antioch Congregational Church, and we had the funeral there.

. . . The people of Los Gatos were very kind indeed; I never saw a better feeling manifested anywhere. All seemed determined to do any and everything for the comfort of the family in their affliction.

Your affectionate brother,

H. W. Baker

Formal and aloof, this letter epitomizes the breach between the California branch of the Baker family and the one son— my great-grandfather—remaining in Utah. The letter, like Jean Rio’s last will and testament, does not begin to explain the life of this remarkable woman. Among the mysteries is how she happened to die in Los Gatos, a small village at the base of the Santa Cruz Mountains seventy-five miles south of Antioch. She had apparently moved there with her son John and his family. Famous for its sanitariums, the town had become a center for patients suffering from respiratory problems, including tuberculosis, but there is no evidence that she or any of her family members had such an affliction. In 1881, thirty-eight-year-old John had become very ill and had taken to performing his legislative business from a hotel bed in Sacramento. He died quite suddenly that year. He is buried in the state plot at the California capitol.

On June 6, 1882, Jean Rio drafted her final will.

I, Jean Rio Pearce (née Baker), widow, being of sound mind and in physical health, do make this my last will and testament. I have lived (and hope to die) in firm belief and faith in Jesus Christ, as the son of God, the only atonement for sin, and the only way of salvation. It is my express desire that my body be placed for burial, in a quite plain redwood coffin, without any manner of ornamentation, and that I be buried as near as possible to my grandson, Chauncy Rio Baker. And that my elder sons, and grandsons, act as attendants at my funeral, and themselves lower my Body into the grave.

Naming her oldest son, Henry Walter Baker, her executor, she dispersed property equally among her four surviving children, Walter, William, Charles, and Elizabeth, with John’s share going to his two young daughters. It was an estate worth approximately $35,000 by today’s standards.

In the end, for all the thousands of words she wrote, much of her life remains shrouded. I reassembled her story from untold shattered pieces. In doing so I met and corresponded with dozens of her descendants—the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Walter, William, Charles, Elizabeth, and John—many of whom had had tiny shards of oral history handed down to them. Except for the Utah descendants of William, these “cousins” were uniformly unaware of the Baker family’s Mormon experience, so anonymously assimilated in secular California life had Jean Rio and her sons and their descendants become.

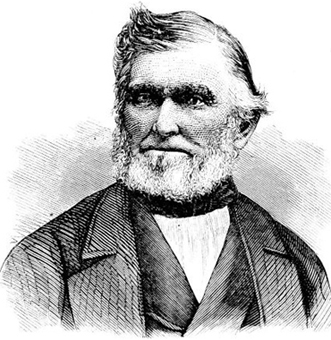

The California Bakers remained in the Antioch and San Francisco vicinities for the following generations. As for William’s descendants, most of the children from his first family remained faithful members of the Mormon Church, while many of those born to my great-grandmother Nicolena, including my grandmother Hazel, left the faith. Following church president Wilford Woodruff’s proclamation abolishing the Mormon practice of polygamy in 1890—which meant that only the first wife could be legally recognized—Nicolena was left to fend for herself and her large family in a primitive village in south-central Utah. Ironically, Woodruff had been the missionary who had converted and then baptized William Baker as a young man in London. In one of those strange twists of fate, Woodruff issued the edict that would send William Baker into hiding and ultimately result in his incarceration as a polygamist. Ordered to divide his property and cash among his two families, and required to provide for them financially, he found the task impossible. Despite his ample income, there was simply not enough to support two wives and eighteen children—two of Hannah’s and three of Nicolena’s had died.

Mormon apostle Wilford Woodruff, who as a young missionary had

baptized William George Baker in London in 1849

.

His proclamation

abolishing polygamy forty-one years later would make criminal

fugitives of William George Baker and other men who devoutly

practiced polygamy.

Nicolena suddenly found herself a forty-five-year-old mother of seven with little if any outside support. She, like hundreds of other polygamist women in her position, received no financial aid from the church, of which she had been a devout member for some thirty-five years since her epic walk across the country to Zion. Nor was the husband upon whom she was depending to pull her “through the veil” to everlasting deliverance able to provide much assistance. He wrote to her while a fugitive from the U.S. marshals.

Dear Lena,

Tell Bro. Warrock I will send the rent to him in a few days. Do not be uncaring about me, as I shall return soon . . . it is not wisdom for me to come home. If you knew how disappointed I feel I know you would favor me with a letter, tell me all of the news, especially what is being done by [the] court.

Give my love and kisses to the children and be assured I am still lovingly yours—

W.G.B.

You must enclose your letter to me sealed inside of another envelope addressed to “Sam E. Jost,” Ogden City, Utah.

Still, the adversity seems to have strengthened her own faith, as she continued tithing her diminutive income while she disappointedly watched her children fall away from the church. In the 1890s she boldly ventured into a millinery business, earning enough to support her children and even provide them with an education. When William died in 1901 he received a substantial obituary reflective of his long-standing stature in the community of Richfield. Neither Nicolena nor any of his children by her was named as next of kin. Like the thousands of other children of polygamists, they were treated as if they were illegitimate and in effect punished by disinheritance and social stigma by the very society that had sanctioned and encouraged the practice of polygamy.

So what do we know of Jean Rio Griffiths Baker Pearce? We are sure of her deepest faith. We are sure of how much she loved her family and of how much they loved her. We are sure of what she expected of the new Zion in America, and therefore we know how deep her disillusionment with that society and culture was, how repelled she was by the suppression of women, by the avarice of this “Kingdom of God upon Earth,” by the atrocity of Mountain Meadows. She took her family and most of her material possessions, including her beloved piano, and crossed half a world in search of a community of faith that would bring into practical existence the principles of the New Testament that she believed in—compassion, tolerance, love, reconciliation. What she found instead was a patriarchal theocracy fiercely committed to prejudice and material greed, turning upon its own members the weapons of fear and intimidation that had been used against the faith in its infancy. But we can be sure that as her disillusionment grew she faced it the same way she had faced her other trials—the deaths of her husbands and children, the storms at sea. We have the testimony of her granddaughter: Jean Rio met “the most terrifying situations with a calmness of spirit. She had compassion for the downtrodden, sympathy for the underprivileged.”

In my view, what Jean Rio came to at the end of this century of tumult, of promise and betrayal, was a very modern theology—a tolerance that led her to hope for a community of faith irrespective of creed. The twenty-first century is undergoing throughout the world a clash of creeds more ferocious and dangerous than anything in Jean Rio’s world. We have never been more in need of the tolerance, respect, and freedom from religious dogmatism that she embodied, the principles she hoped to leave to posterity. In search of fundamental Christianity, she came to the conclusion that fundamentalism was narrow and barren. In search of a kind of organizing creed, she understood that creed often confines rather than enables true faith. Crossing a world to find a material or geographical place of enlightenment, she, like many seekers, found that her spiritual home had always been within herself.

She was one of the more notable apostates of the Mormon Church, yet the church never acknowledges her apostasy. She was one of the most disillusioned converts to the faith, and yet she is used as a recruitment and proselytizing tool in the Museum of Church History’s video display. She represents one of the religion’s more notable failures, and yet she is advertised as one of its successes.

For so many years, Jean Rio was deprived her voice. Then the church distorted it. My goal has been to restore it.